Mawlāy ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz Dabbāgh: Biography of a Saint in an Age of State-Building

In the topography of Moroccan Sufism, sainthood often appears in pairs. In the 7th/13th century, we encounter ʿAbd al-Salām Ibn Mashīsh (d. 622/1225) and his disciple Abū ʼl-Ḥasan al-Shādhilī (d. 656/1258); five centuries later, the couple Abū Fāris ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz ibn Masʿūd al-Dabbāgh (d. 1132/1720) and Abū al-ʿAbbās Aḥmad ibn al-Mubārak al-Sijilmāsī (d. 1156/1743) occupies a structurally similar place. Both pairs enact the same spiritual drama: a "hidden" Moroccan pole (quṭb)—noble in lineage (sharīf), socially marginal, and portrayed as unlettered—whose authority rests on sainthood (wilāya) and Muhammadan inheritance (wirātha); alongside a highly trained jurist-scholar, often emerging from rural environments, who translates that ineffable experience into disciplined discourse, devotional liturgy, and institutional memory.

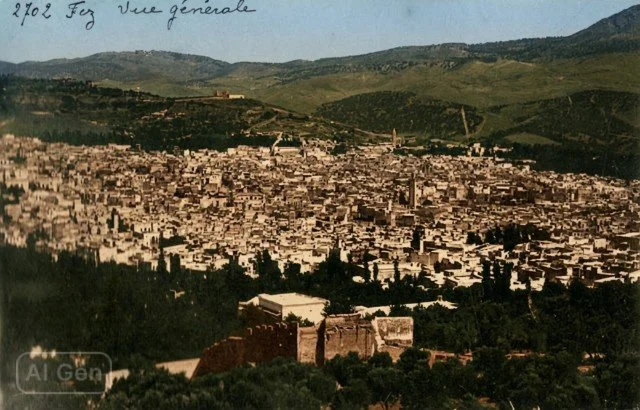

Yet the case of al-Dabbāgh exceeds the purely dyadic model. His emergence in early 18th-century Fez must be situated within a triple field of authority that defined ʿAlawī Morocco: the empire centered in Meknes, commanding military force and administrative apparatus; the scholarly establishment of al-Qarawiyyīn, wielding juridical legitimacy and intellectual prestige; and the Idrisīd sharifian lineages of Fez, whose claims rested on genealogical proximity to the Prophet ﷺ and the charismatic distribution of baraka. Al-Dabbāgh's appearance introduced what this study terms "the third authority": a form of spiritual sovereignty that operated outside formal institutions yet claimed jurisdiction over the invisible architecture of the cosmos itself.

When al-Dabbāgh declared that the entire heavenly council (dīwān al-ṣāliḥīn) was gathered within his chest, or that his inner self (dhāt) encompassed the Throne and the worlds beyond it, these were not merely mystical metaphors but assertions of a spatial and ontological sovereignty that subtly repositioned the axis of power in a city torn between competing claimants. His statements that he bore within himself "robes" of divine energy capable of dissolving Fez itself, or that he had surpassed the great saints of earlier centuries, carried unmistakable political resonance in a Morocco where saintly prestige could rival—and occasionally threaten—royal authority.

Several elements intensified the potential challenge this third authority posed. First, his spiritual initiation came not through traditional silsila but through direct encounter with al-Khiḍr, effectively bypassing the established shaykh-murīd structures that regulated Sufi authority and suggesting that authentic wilāya could manifest through divine appointment alone. Second, his claims to khatmiyya—the sealing or culmination of sainthood—positioned him as the final synthesis of Muḥammadan inheritance, a station that required no external validation. Third, as an Idrisīd sharīf whose lineage connected him to the founding dynasty of Fez itself, his authority resonated with the city's deepest historical memory, positioning him as heir to a spiritual sovereignty that predated the ʿAlawī state.

The Custodian

El Hassane Debbarh, founder of DAR.SIRR and grandson of Mawlay ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz al-Dabbāgh, engaged in the physical restoration of the shrine in Fez—an image symbolizing continuity of transmission, custodianship of memory, and inheritance of the spiritual sciences and stations articulated by the Shaykh in Al-Ibrīz through service, responsibility, and lived presence.

The original title of Ibn al-Mubārak's work—al-Tāj wa-al-Ibrīz (The Crown and Pure Gold)—encoded this dual claim: the crown signifying sovereignty over the invisible hierarchy of saints, and the pure gold representing the uncorrupted essence of prophetic inheritance transmitted directly through wirātha Muḥammadiyya. The title's invocation of "the Crown" carried another profound symbolic weight in Fez, where Mawlāy Idrīs II—the city's founder and patron saint—was popularly known as Moul al-Tāj (The Owner of the Crown), signifying his spiritual sovereignty over the empire and its inhabitants. By naming the work al-Tāj wa-al-Ibrīz, Ibn al-Mubārak implicitly positioned al-Dabbāgh's authority within the same register of spiritual sovereignty, suggesting that the "crown" of saintly jurisdiction had passed from the founding Idrisīd pole to his descendant, while the "pure gold" represented the unalloyed prophetic knowledge that authenticated this transmission.

The collaboration with Aḥmad ibn al-Mubārak represents the moment this third authority achieved textual permanence and scholarly legitimation. Yet the significance of this partnership extended beyond the mere transcription of charismatic utterance: the pairing of al-Dabbāgh (descendant of the Prophet ﷺ through al-Ḥasan ibn ʿAlī) and Ibn al-Mubārak (descendant of Abū Bakr al-Ṣiddīq) created a symbolic convergence at the level of lineage that lent their collaboration a legitimacy that neither genealogy alone could have secured. Al-Dabbāgh's illiteracy was not merely a marker of spiritual authenticity but a strategic positioning that allowed him to transcend the jurisdictional boundaries separating sultanic, scholarly, and sharīfian forms of legitimacy. His authority was deterritorialized—anchored not in land, zawiya endowments, or institutional structures, but in a claim to immediate cosmic perception.

Through Ibn al-Mubārak's al-Tāj wa-al-Ibrīz, later known as Al-Ibrīz Min Kalām Sayyidinā ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz (Pure Gold from the Words of Our Master ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz), the teachings of an illiterate Moroccan saint became one of the densest and most ambitious syntheses of late pre-modern Sufi thought. This collaborative project offers a rare model in which ʿilm ladunī (divinely-bestowed knowledge) is not merely narrated but structurally naturalized within academic, juridical, and scholarly discipline, effectively translating cosmic sovereignty into scholastic currency and securing al-Dabbāgh's third authority a permanent place in the transmitted tradition.

By situating al-Dabbāgh within this triangulated field—between throne, university, and shrine—this study reveals how Moroccan Sufism developed a sophisticated architecture of power that neither simply accommodated nor directly opposed political authority, but rather operated on a parallel ontological plane. The paper maps the tripartite structure of authority in ʿAlawī Morocco, examining how Mawlāy Ismāʿīl's centralizing project (1672–1727) created pressure on alternative centers of legitimacy; analyzes al-Dabbāgh's cosmological claims, Khiḍrian initiation, khatmiyya declarations, and Idrisīd heritage as constituting a form of invisible sovereignty; and examines how Ibn al-Mubārak's transcription project transformed charismatic utterance into canonical text. Al-Dabbāgh's life and legacy demonstrate that in contexts where multiple forms of sovereignty compete, sainthood can constitute not merely a spiritual status but a distinct mode of governance—one whose jurisdiction extends over domains (the heart, the cosmos, the invisible council of saints) that remain permanently beyond the reach of sultans and scholars alike.

1. The Five-Century Journey of a Sharīfian Lineage Between Fez and Granada

Mawlāy ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz was born in Ḥūmat al-ʿUyūn, the "Quarter of Springs," in the Qarawiyyīn ʿAdwah of Fez on the evening of Saturday, 12 Ṣafar 1095 AH (30 January 1684 CE), in the shadow of Sultan Mawlāy Ismāʿīl's reign (r. 1083–1139/1672–1727)—an era of political consolidation, strict discipline, and a flourishing but tense scholarly life. The year of his birth coincided with the young sultan's expulsion of the English from Tangier, marking the beginning of the Alawid systematic campaign to reclaim Moroccan territory from European powers and assert absolute sovereignty over the empire's coastal frontiers. He entered the world in Fez as the firstborn son, a long-awaited child whose birth the family remembered as a moment of radiant promise. His lineage was Idrisīd, carried through the noble Dabbāghī branch descending from al-Muntaṣir Billāh Abū al-ʿAysh ʿĪsā ibn Idrīs ibn Idrīs ibn ʿAbd Allāh ibn al-Ḥasan ibn al-Ḥasan ibn ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib (233/847)—an ancestry that placed him within the oldest sharīfian bloodline of Morocco.

Yet the path that brought his family to Fez traced a geography of exile and return that spanned five centuries. His ancestors had ruled from the highland fortress of Āyt ʿAtāb in Tadla, but the collapse of Idrisīd sovereignty and the campaigns of Umayyad-allied forces drove them—along with other Idrisīd branches—from their ancestral territories. They fled first to the mountain stronghold of Qalʿat al-Nasr, then scattered: some settled in Sabta, while a crucial ancestor—Abū al-Ḥasan ʿAlī ibn ʿAbd al-Raḥmān [al-Dākhil] (fl. 479/1086)—crossed to al-Andalus at the explicit invitation of the Almoravid sultan Yūsuf ibn Tāshfīn, who brought him along bi-qaṣd al-tabarruk bihi (for the purpose of seeking blessing through him).

The genealogist Sulaymān al-Ḥawwāt, in his treatise Qurrat al-ʿUyūn fī al-Shurafāʾ al-Qāṭinīn bi-Ḥūmat al-ʿUyūn (The Delight of Eyes Concerning the Sharīfs Residing in the Quarter of Springs), preserves this detail as evidence of the family's standing: they crossed not as refugees but as consecrated figures whose baraka was solicited by the very sultan who was unifying the Maghrib and defending al-Andalus. Al-Dākhil settled in Granada, where his descendants would achieve prominence as judges, scholars, and occasionally diplomats. The most celebrated among them was Abū al-Qāsim Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad, known as al-Sharīf al-Gharnāṭī (d. 760/1359), who served as chief judge (qāḍī al-jamāʿa) of Granada and khaṭīb of the Alhambra mosque under the Naṣrid sultans. His teaching circle included some of the most luminous intellects of the Islamic West: Ibn al-Khaṭīb, Ibn Khaldūn, al-Shāṭibī, and Ibn Juzayy.

Yet even this eminence could not withstand the tightening grip of Christian reconquest. According to al-Sulamī’s al-Ishrāf ʿalā Baʿḍ man Ḥalla bi-Fās min Mashāhīr al-Ashrāf (Supervision of Some Celebrated Sharīfs Who Settled in Fez), his direct ancestor, Abū al-ʿAbbās Aḥmad ibn Muḥammad [al-Qādim] (fl. 796/1393), departed Granada and returned to Morocco, settling in Salé on the Atlantic coast. There, the Marīnid sultan al-Mustansir Billah (796/1394) bestowed upon the family a privilege that would mark them for generations: control over the revenues of the city's tannery (Dār al-Dabbāgh). This was no ordinary craft workshop but a major state enterprise, its leather goods supplying markets across the Mediterranean and generating substantial income for the empire. From this fiscal connection—not from any involvement in the actual labor of tanning—the family acquired the name al-Dabbāgh, transforming a mark of Marīnid patronage into a lasting surname.

Only in the early ninth/fifteenth century did the family patriarch, ʿAbd al-Raḥmān ibn al-Qāsim [al-Jāmiʿ] (fl. 900/1494), lead the clan back to Fez—the city their Idrisīd forebears had founded and from which they had been expelled centuries before. His return was not an isolated act but part of a broader movement: as the Marīnid state weakened and the Waṭṭāsid dynasty prepared to ascend, Idrisīd shurafāʾ began flowing back to Fez from their scattered refuges across Morocco. According to ʿAbd al-Salām al-Qādirī in al-Durr al-Sannī, the Dabbāgh family were among the very first of the Idrisīd lineages to make this return, preceding the larger wave of sharīfian resettlement that would transform Fez's social landscape in the late fifteenth century. The significance of this moment was such that al-Qādirī commemorated it in verse in his Durrat al-Mafākhir:

وَقُرْبَ تِسْعَمِائَةٍ بِلَا خَفَا * كَانَ دُخُولُ فَاسْ جُلّ الشُّرَفَا

Near the year nine hundred, without exception,

was the entry into Fez of most of the shurafāʾ.

Over the two centuries separating ʿAbd al-Raḥmān [al-Jāmiʿ] from his great-great-great-grandson Mawlāy ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz, the Dabbāgh family established a pattern that would define their presence in Fez: a quiet synthesis of sharīfian descent, juridical learning, and Sufi inclination, rooted in the same narrow streets of Ḥūmat al-ʿUyūn where their patriarch had first settled. Generation after generation produced jurists, grammarians, and men of letters who moved through the madrasas and mosques of Fez without seeking prominence, their scholarship solid but never spectacular, their piety evident but deliberately concealed. They witnessed the collapse of Granada in 897/1492 from across the strait—and shortly thereafter, watched the last Naṣrid sultan, Abū ʿAbd Allāh Muḥammad al-Zughbī (r. 887–897/1482–1492), arrive in Fez as a refugee, the kingdom their ancestors had served now reduced to memory. They lived through the rise and fall of the Waṭṭāsids, the meteoric ascent of the Saʿdid shurafāʾ from the Draa Valley, and finally the consolidation of ʿAlawī rule under the ruthless efficiency of Mawlāy al-Rashīd (r. 1075–1082/1664–1672) and his brother Mawlāy Ismāʿīl.

Through these upheavals, the family maintained its position not through courtly ambition or military service but through a calculated invisibility—what later sources would describe as istithār bi-al-khumūl, the deliberate embrace of obscurity as a mode of survival and spiritual refinement. Yet this obscurity was never total. The family remained connected to the city's scholarly networks, their names appearing occasionally in ijāzāt and fahrasa literature, their presence noted by contemporaries as men of learning and baraka even if their works rarely circulated beyond Fez. The family's rootedness in Ḥūmat al-ʿUyūn became almost symbolic: their first house, acquired by ʿAbd al-Raḥmān, remained in family possession across the centuries, a physical anchor in a city where political power shifted violently but sharīfian prestige endured.

It was into this inheritance—two centuries of accumulated learning, lineage, and deliberate hiddenness—that Mawlāy ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz’s father, Masʿūd ibn Aḥmad (d. 1111/1699), was born. A respected Mālikī jurist and accomplished grammarian, Masʿūd authored a commentary on Ibn Mālik's Alfiyya that survives in the Ḥasaniyya Library, along with other works on grammar, morphology, and literature. His scholarship placed him within the long Dabbāgh tradition of linguistic expertise that stretched back to al-Sharīf al-Gharnāṭī's commentaries on prosody and rhetoric. Yet his true orientation lay elsewhere. Sources describe him as drawn to Sufism, inclined toward khumūl (withdrawal from public life), and marked by a baraka that his contemporaries recognized even as he refused to cultivate it.

The family's standing received formal recognition in 1082/1672, when Sultan Mawlāy al-Rashīd issued a ẓahīr sharīf granting Masʿūd control over the endowments (futūḥāt) and gifts (hadāyā) of the shrine of the saint ʿSidī Alī ibn Ḥarazim (d. 559/1163)—one of the most venerated burial sites in Fez. This was no minor administrative appointment but a recognition of the family's spiritual authority and their role as custodians of sacred space. The timing was significant: that same year, Mawlāy al-Rashīd died in Marrakech, and his brother Mawlāy Ismāʿīl—who would go on to build the most centralized state Morocco had seen since the Almohads—transported his body to Fez and buried him at the shrine of ʿAlī ibn Ḥarazim on Monday, 17 Ṣafar 1083/10 June 1672. From that moment, the site became a royal mazāra, reserved for sultans, scholars, and members of the royal household. The Dabbāgh family, entrusted with the shrine's administration, thus found themselves positioned at the intersection of ʿAlawī dynastic authority and Fāsī saintly prestige—stewards of a space where political power sought legitimation through proximity to baraka.

He married Fāriḥa, the daughter of ʿAllāl al-Qamarshī, a wealthy merchant from an Andalusian Khazrajī family. This family had fled Málaga after the Catholic Monarchs confiscated their properties, eventually settling in Meknes, where they established themselves in commerce. Together they had three sons: ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz, al-ʿArabī, and ʿAlī. When Masʿūd died—relatively young, leaving his eldest son ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz barely sixteen—he was buried beside the tomb of ʿAlī ibn Ḥarazim, the very shrine his family had been appointed to oversee. His grave, modest and unmarked in the style he had cultivated in life, lay within a necropolis that now included an ʿAlawī sultan, a testament to how far the family had come from their exile in Salé.

Yet destiny had prepared something else entirely for his eldest son. For two centuries—from the family's return to Fez in the early 800s/1400s through Masʿūd's own generation—every male Dabbāgh of note had been a scholar: jurists, grammarians, men who moved fluently through the transmitted sciences and contributed, however modestly, to the intellectual life of Fez. ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz would be the exception—the only illiterate member of the family in this entire span. And this was not mere misfortune. Destiny seemed to have seized him deliberately, stripping him of the very tools that had defined his lineage: literacy, formal education, access to the madrasas where his father and grandfather had studied. His father's early death left him responsible for his younger brothers while still a boy himself. Instead of studying in the madrasas of Fez, he worked—weaving, small trades, any task that paid enough to feed the house.

The city's scholars saw him as another poor boy from the quarters of Fez al-Bālī, destined to labor rather than to learn. Nothing suggested that this youth, who could barely read or write, would become the spiritual axis of his generation. Yet the very shrine his father had overseen—the tomb of ʿAlī ibn Ḥarazim, where an ʿAlawī sultan now lay and where his own father rested—would become the site of his transformation. It was there, outside that blessed mausoleum, that the orphaned craftsman would encounter al-Khiḍr, the Green Guide who appears to those chosen for knowledge that bypasses books, masters, and all the apparatus of formal learning. What his family had cultivated through two centuries of scholarship, he would receive in a single meeting with a figure who stands outside time itself.

2. The Ṭarbūsh and the Twelve Years

The destiny of Mawlāy ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz unfolded in the realm of al-bushrā and glad tidings long before his birth. His mother’s uncle, Abū Ḥāmid Muḥammad al-ʿArabī ibn Aḥmad ibn ʿAbd al-Karīm al-Fishtālī (d. 1090/1679), received a vision from the Prophet ﷺ announcing the coming of a great walī, a child who would rise from his sister’s daughter Fāriḥa and bear the name ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz. With this prophecy, an unseen current of baraka began tracing its way toward a child yet unborn.

Al-Fishtālī, who had studied under the great masters of his age—Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad al-Dirʿī (d. 1085/1674), ʿAbd al-Raḥmān ibn al-Qāḍī (d. 1082/1671), and ʿAbd al-Qādir al-Fāsī (d. 1091/1679)—and had refused all offers of judgeships, understood what was required of him. He raised his niece with profound care, sheltering her in his modest household, providing for her from his own earnings. He had settled in Raʾs al-Jinān, where he served as imam and teacher, instructing children in Qurʾān recitation in his small mosque. And when the time came, he called aside one of his students—a young sharif named Masʿūd al-Dabbāgh—and proposed a marriage.

The convergence of names alone seemed to carry a hidden message: Masʿūd, "the fortunate one," would marry Fāriḥa, "the joyful one," daughter of Rāḍiya, "the contented one." The proposal was direct, unadorned. Masʿūd, perhaps startled that a man of al-Fishtālī's station would offer him such a match, accepted immediately. The walī insisted on bearing all expenses himself: the dowry, the preparations, every detail. After the wedding, he continued his care, summoning Masʿūd daily to his shop in Simāṭ al-ʿUdūl and placing two small silver coins in his hand—a quiet subsidy, sustained over months and years, to ensure the young household's stability. Witnesses remembered seeing Masʿūd arrive each afternoon after ʿAṣr prayer, waiting as al-Fishtālī finished his work, then receiving the coins that would feed his family for another day. It was an act of tarbiya disguised as generosity, a shaping of circumstances that would allow the prophesied child to be born into the right lineage, the right household, the right conditions.

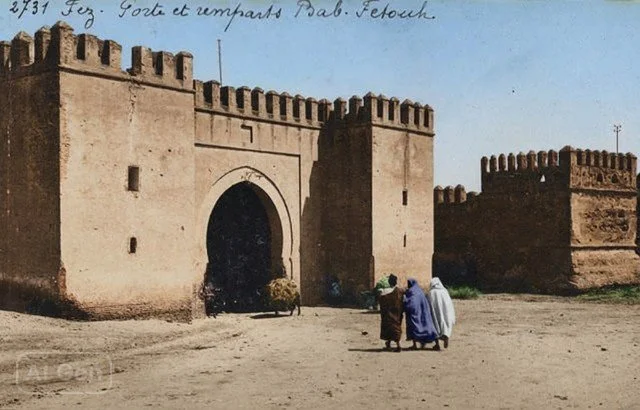

Before al-Fishtālī departed this world—five years before the child's birth—he prepared two objects: a ṭarbūsh and a pair of ṣabbāṭ. These were not heirlooms in the ordinary sense but vessels charged with baraka, physical objects that had absorbed the spiritual presence of the man who wore them. He entrusted them to the family with instructions that they be given to the boy when the time came, when the hidden inheritance could be activated. Then he died and was buried outside Bāb al-Futūḥ, near the tomb of ʿAlī Aḥmāmūsh, leaving behind a set of instructions that would take years to fulfill.

ًWhen the boy was born in al-ʿUyūn, the quarter his ancestors had settled two centuries earlier, his father named him ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz, fulfilling the prophecy. For the first years of his life, nothing suggested he was anything other than what he appeared: the eldest son of a respected but modest scholar, a boy growing up in the narrow streets of Fez al-Bālī, learning the rhythms of prayer, family, and the markets. And then, one day, his mother gave him the objects al-Fishtālī had left behind. When he placed the ṭarbūsh on his head and slipped his feet into the ṣabbāṭ, something erupted. Heat tore through his body—so fierce, so overwhelming, that his eyes filled with tears and he could not speak. The baraka that had been promised before his birth, that had moved through marriages and deaths and whispered instructions, suddenly ignited.

From that moment, he was no longer the boy who worked in the workshops. A hunger opened inside him that nothing in Fez could satisfy—not the mosque lessons, not the dhikr circles, not the respected shaykhs whose zāwiyās dotted the city. He began to wander. Twelve years of wandering, from one shaykh to another, adopting litanies and abandoning them, sitting in majālis that promised illumination but delivered only formulas. Every master he met seemed to offer a piece of the answer but never the whole. Every wird he recited opened a door but led only to another locked gate. The constriction grew tighter, the yearning sharper, until he became a figure suspended between two worlds: his hands still worked wool and silk, but his heart had already crossed into the realm of meanings. He was searching, though he did not yet know for whom. Destiny had arranged everything—the marriage, the death, the ṭarbūsh, the hunger—but the final meeting, the one that would unlock what had been placed inside him, still lay ahead. Somewhere in Fez, unseen and waiting, was the master for whom all of this had been prepared.

3. from Hidden Saints to Prophetic Presence

The twelve years that Mawlāy ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz spent searching across Fez unfolded within a precise framework of places, relationships, and inner signs. His wandering was not aimless; it developed within a constellation of scenes that destiny placed around him—his early marriage, his inherited bond with the shrine of Sīdī ʿAlī ibn Ḥarazem, and a circle of hidden saints who did not guide him through formal teaching but through encounters that opened new interior capacities long before the arrival of al-Khiḍr:

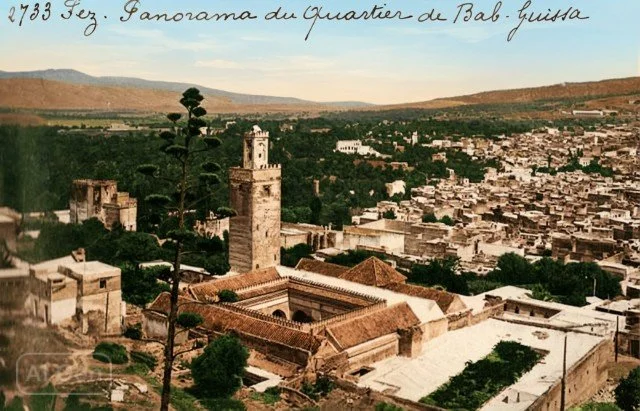

ʿUmar ibn Muḥammad al-Hawwārī ( 1125/1713): He was the first of the three. An ascetic from the Hawwāra lineage of the Sous, he served as the caretaker of the very shrine tied to al-Dabbāgh’s family. Their acquaintance grew through quiet exchanges, and although al-Hawwārī rarely spoke of his state, al-Dabbāgh later affirmed that his station was immense. When al-Hawwārī passed away and was buried outside Bāb al-Futūḥ, al-Dabbāgh remarked that had people known his reality, “they would not have visited anyone else from among the living.” Three days after his death, the first subtle movements of unveiling began.

Manṣūr ibn Aḥmad ( 1125/1713): A few years later came his meeting with Manṣūr ibn Aḥmad, around the age of twenty-three, seven years before the great opening. Their first encounter happened inside a weaving workshop into which al-Dabbāgh had entered to arrange training for his younger brother al-ʿArabī. Manṣūr called him aside, questioned him with simplicity and insight, and then placed thirty silver coins in his hand, sealing a recognition that deepened over the years. Al-Dabbāgh would later say that many extraordinary events occurred in Manṣūr’s company, though Al-Ibrīz recorded only a few. Manṣūr’s passing marked the end of an era of preparation.

Muḥammad al-Lihwāj ( 1125/1713): The third was Muḥammad al-Lihwāj, whom he met even earlier, around 1112/1700, in another workshop linked to relatives of the saint. Each time al-Lihwāj visited, he would sit beside the young ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz and engage him in private conversation as though recognizing a hidden potential that had not yet emerged. Their familiarity grew until, upon al-Lihwāj’s death—shortly after Manṣūr.

One Friday, Mawlāy ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz approached the Ḥarāzimī sanctuary—the same spiritual axis that had shaped Abū Madyan (d. 594/1198). There, in the depth of night, the veil lifted. The Green Guide appeared to him, not as a teacher of tablets but as the inheritor of the hidden knowledge once granted to Moses: the knowledge of divine arrangement, the unseen weave of decree, and the inner architecture by which the soul is led from bewilderment to certainty.

From that nocturnal encounter, al-Dabbāgh received a sacred litany—seven thousand invocations directed toward the Prophet ﷺ—a devotional current that reshaped the composition of his inner life. "O Allāh, O my Lord, by the status (Jāh) of our Master Muḥammad ibn ʿAbd Allāh, unite me and our Master Muḥammad ibn ʿAbd Allāh in this life before the Hereafter." For four uninterrupted years (1121–1125/1709–1713), he carried this wird with unwavering exactitude, reciting it until its rhythm became inseparable from breath, heartbeat, and consciousness.

Throughout this period, he remained in the quiet orbit of the three hidden saints of Fez—al-Hawwārī, Manṣūr, and al-Lihwāj. Their companionship did not provide instruction in the conventional sense; it functioned instead as a silent confirmation, a spiritual climate in which the litany could mature into vision. Each of them recognized the inward ascent taking shape within him, even as its final form remained veiled.

As the fourth year drew to its close, and with the passing of al-Hawwārī on Thursday, 8 Rajab 1125 / July 31, 1713, the inward edifice completed itself. The long discipline of the litany, the quiet companionship of the concealed saints, and the unseen promise carried through his lineage converged—preparing the ground for the great opening that would descend upon him at Bāb al-Futūḥ.

After the passing of al-Hawwārī, the custodian of the Ḥarāzimī sanctuary, on Thursday, 8 Rajab 1125 / July 31, 1713, and at exactly thirty years of age, the divine disclosure unfolded. Approaching Bāb al-Futūḥ, his senses dissolved; light surged through him; creation appeared as a single, seamless unveiling—the earth and its layers, the heavens and their orders, the seas and their depths, all perceived with a clarity that felt like remembrance rather than discovery.

“… When I reached Bāb al-Futūḥ, a shiver entered me, then intense trembling, then my flesh began to tingle greatly. I kept walking—while in that state, and the condition kept increasing. My chest began to heave violently, until my collarbone was striking my beard. Then something emerged from my inner being (dhāt), like the steam from a couscous pot. Then my inner being began to elongate, until it became taller than anything tall. Then things began to unveil themselves to me and appear as if they were right before me. I saw all the villages, cities, and hamlets. I saw everything on this land. I saw a Christian woman sing her child in her lap. I saw all the seas. I saw the seven earths and everything in them of creatures and created beings. I saw the sky as if I were above it, looking at what was in it.And behold, a great light like flashing lightning that comes from every direction—that light came from above me, from beneath me, from my right, from my left, from before me, and behind me. A tremendous cold struck me from it, until I thought I had died. I rushed and threw myself face-down so I would not look at that light. But when I lay down, I saw that my entire being had become eyes: the eye sees, the head sees, the foot sees, all my limbs see. I looked at the clothes I was wearing and found they did not veil that sight which had spread through my being. I knew then that lying face-down and standing upright were equal.Then the state continued with me for an hour and ceased, and I returned to the condition I had been in at first. I returned to the city—I was unable to reach Sīdī ʿAlī ibn Ḥarazim—and I feared for myself and occupied myself with weeping.. Then that state returned to me for an hour, then ceased. It kept coming to me for an hour and ceasing for another hour, until it became familiar with my being (dhāt). Then it would disappear for an hour during the day and an hour during the night, then it stopped disappearing altogether.”

The day of the great opening marked a decisive rupture in the life of Mawlāy ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz. Its force overwhelmed the limits of the physical body, driving him into movements that revealed the dominance of spirit over form. The experience announced the beginning of a new mode of existence in which the boundaries separating the sensory world from the unseen no longer held their conventional meaning.

When dawn came, he sought grounding in the ancestral axis of Mawlāy Idrīs II. On the road, the notable jurist-saint Abū al-ʿAbbās Aḥmad al-Jīrūndī ( 1125/1713) recognized the extraordinary nature of what had occurred and directed him toward the tomb of the ancient ascetical Abū ʿAbd Allāh al-Tāwudī ibn Sūdah (580/1184), outside Bāb al-Jīsa. This guidance initiated a chain of events that would bring him to the figure destined to stabilize his unveiling.

As he approached Bāb al-Jīsa, a stranger of striking presence appeared: ʿAbd Allāh al-Barnāwī (1126/1714), a figure of the Qādirī Sufi lineage who had traveled from the region of Bornu in Sub-Saharan West Africa. His arrival in Fez had been governed by spiritual intention, and the convergence with al-Dabbāgh revealed that his journey had been oriented entirely toward this encounter.

Al-Barnāwī accompanied him to his residence in Rās al-Jinān. Over the following months—through the remainder of Rajab and the successive months of Shaʿbān, Ramaḍān, Shawwāl, Dhū al-Qaʿda, and the first ten days of Dhū al-Ḥijja—he fulfilled a precise role. He stabilized the young saint’s inner state, eased the turbulence produced by the great opening, and helped his consciousness adapt to the continuous influx of light. His influence was not pedagogical in the conventional sense; it was a presence that harmonized, grounded, and refined.

Al-Dabbāgh later described al-Barnāwī as a pole among the cosmic hierarchy of saints, nourished by the radiance of more than seventy of the Divine Names. Through him, the final purification required for the Muhammadan unveiling took place. The four years of reciting the Khidrian litany had prepared the heart; the great opening had unveiled creation; but the clarity necessary for direct vision of the Prophet ﷺ required a final calibration that al-Barnāwī alone was able to transmit.

When the appointed day came — the third morning after ʿĪd al-Aḍḥā — the Khidrian litany reached its destination. While still in Fez, al-Dabbāgh’s inward sight oriented itself spontaneously toward the precinct of the Prophet’s sanctuary in Madinah. The noble chamber came into view, the light intensified, and out of its radiance the Prophetic form manifested directly, in waking awareness. This was not a dream, nor an internal image, but the full encounter of ruʾyat al-Nabī fī al-yaqaẓa—the definitive awakening of the Muhammadan inheritance within him.

“When Allāh willed to grant me the opening and to unite me with His Mercy, I looked—while I was in Fez—at the Noble Tomb, then I looked at the Noble Light. It began to draw near me—while I was looking at it—and when it came close to me, a man emerged from it, and behold! it was The Prophet ﷺ!”

The transactional logic of sainthood under Ismāʿīl was otherwise brutally clear. Those who aligned their spiritual authority with dynastic ambition prospered; those who did not were erased. Shaykh ʿAlī al-Lawātī stood as the exemplary case. His rise to prominence came not through years of ascetic discipline or volumes of legal scholarship, but through a single prophetic utterance: he delivered glad tidings (bushrā) proclaiming the divinely ordained ascent of ʿAlawī rule. That pronouncement—interpreted by the regime as celestial confirmation of its legitimacy—earned him immediate royal patronage. Zawiyas were endowed in his name, disciples flocked to his teachings, and his reputation spread not because of what he knew but because of whom he had endorsed. His trajectory revealed the new economy of sanctity: baraka aligned with the throne was rewarded with land, wealth, and institutional support; baraka that remained neutral or, worse, attached itself to defeated rivals, was suppressed. Saints who had cast their lot with the Dilāʾī cause found their zawiyas dismantled, their properties confiscated, their names excised from the litanies of blessing recited in mosques. The message was unmistakable—in Ismāʿīl's Morocco, sainthood that served dynastic legitimacy flourished; sainthood that did not, vanished.

This consolidation unfolded alongside relentless warfare across the frontiers. Mawlāy Ismāʿīl waged military campaigns against the Ottomans, defending Morocco's eastern border and asserting that the Sharifian throne would not accept subordination to Istanbul. On the Atlantic coast, he fought to reclaim Moroccan cities from European occupation; victories against Spain and Portugal restored ports and trade routes that had long been lost. These triumphs fortified the dynasty's legitimacy, uniting imperial ambition with the language of religious duty. Yet as the empire expanded militarily, it entered deeper into diplomatic and commercial negotiations with European states. Treaties were drafted, prisoners exchanged, and maritime accords proposed. Some offered genuine strategic benefit, securing naval materials and trade privileges, but not all were welcomed in Fez. The jurists of the Qarawiyyīn, guarding the moral and legal integrity of the realm, resisted agreements they saw as ethically compromising. In this tension between imperial pragmatism and scholarly vigilance, one sees how Fez remained the moral axis of Morocco, even while Meknes claimed political supremacy.

But Fez’s resistance to Meknes was never limited to moral objection or scholarly critique; it could erupt with sudden, organised, and lethal determination. Barely months after Mawlāy Ismāʿīl ascended the throne and buried his brother Mawlāy al-Rashīd at the sanctuary of Sidi ʿAlī ibn Ḥarāzim, the city rose in open revolt. The townspeople turned against the Makhzan garrison, killed the sultan’s appointed commander, and in the course of a single night drove the royal forces from Fez. What followed was even more striking: the city issued a formal bayʿa to the sultan’s nephew, Aḥmad ibn Muḥriz, proclaiming him ruler and inviting him to establish his authority from Taza. This was no riot, no passing disturbance—it was a constitutional act, a deliberate assertion that Fez still claimed the right to determine the legitimacy of kingship in Morocco. Ibn Muḥriz, whose rebellions in the south had hitherto been episodic and unsupported, now possessed what no military campaign could grant him: the sanction of Morocco’s oldest, most prestigious, and most politically conscious city.

Mawlāy Ismāʿīl's response revealed both his ruthlessness and the limits of his power. He laid siege to Fez, and the siege lasted fourteen months and eight days—longer than any of his campaigns against European fortresses, longer than his suppression of tribal revolts. The city's defenses were not primarily military but social and economic: Fez controlled trade routes, commanded the loyalty of surrounding tribes, and possessed provisions and resolve enough to outlast a royal army. When the city finally opened its gates in Shawwāl 1084 (late October 1673), it was not through conquest but through negotiated reconciliation. The sultan pardoned the inhabitants, reappointed officials, and received renewed oaths of allegiance. But the terms were telling: Fez had forced the sultan to the bargaining table. The city could not defeat Meknes militarily, but neither could Meknes simply impose its will. The balance was struck not through submission but through mutual recognition of limits.

Yet the truce was fragile and repeatedly tested. Ibn Muḥriz, emboldened by Fez's earlier support, seized Marrakesh again in Muḥarram 1084 (May 1673) with the backing of his Saʿdī wife and the Shabanāt tribes. His presence in the south, sustained by hopes that Fez might once more rise in his favor, forced Ismāʿīl into a grinding series of campaigns that consumed years and thousands of lives. Not until Dhu'l-Qaʿda 1098 (October 1687)—fifteen years after the initial revolt—did Ibn Muḥriz finally die, killed in a skirmish near Taroudant. Even then, the resistance he embodied was less a product of his own charisma than of Fez's persistent refusal to accept Meknes' absolute sovereignty. The city's willingness to recognize a rival claimant, to expel a royal garrison, and to endure a year-long siege announced a structural reality: Fez possessed a sovereignty of its own, rooted not in military strength but in its status as the symbolic heart of Moroccan Islam.

This duality—imperial consolidation from Meknes, spiritual and political autonomy from Fez—produced a landscape of permanent tension. The sultan relied on Fez's scholars for moral legitimacy; their fatwas sanctioned his rule, their prayers in the Qarawiyyīn lent his reign divine approval. Yet he could never fully trust them, for their authority derived not from his appointment but from centuries of accumulated prestige. The jurists shaped public sentiment, arbitrated disputes that royal courts could not touch, and preserved a vision of Islamic governance that predated the ʿAlawīs and would, they presumed, outlast them. Fez was honored in official rhetoric, granted privileges and exemptions, yet never subdued. The killing of Ibn Zaydān, the sultan’s administrator who attempted to enforce the conscription of the Ḥarāṭīn—the Black free communities—into the ʿAbīd al-Bukhārī, the slave-army engineered to serve the throne alone, offered a stark reminder that certain boundaries between Meknes and Fez could not be crossed without igniting revolt. When Meknes pressed too far, Fez killed the messenger and dared the sultan to answer. And Mawlāy Ismāʿīl, formidable as he was, calculated that the price of crushing Fez outright exceeded any advantage to be gained. The city remained, therefore, a zone of negotiated domination: loyal in appearance, but autonomous in practice—acknowledged by the throne, yet never fully subdued by it.

Mawlāy Ismāʿīl's wariness of alliances between religious authority and political ambition was not abstract paranoia but bitter experience. Over the course of his reign, he executed three of his own sons for precisely such conspiracies. Each had attempted to mobilize regional scholars and saints, believing that spiritual endorsement could translate into viable claims to the throne. The first was Mawlāy Muḥammad al-ʿĀlim, widely regarded as capable and learned, who governed Marrakesh with such justice that his reputation threatened to overshadow his father's. When he rebelled in 1114/1703, drawing support from southern scholars and rural saints who saw in him a more pious alternative to Mawlāy Ismāʿīl's brutal pragmatism, the sultan moved decisively. Al-ʿĀlim was captured, and in a public demonstration meant to erase any ambiguity about the consequences of rebellion, Mawlāy Ismāʿīl ordered his right hand and left foot severed. The young prince bled to death within days, and the sultan forbade funeral prayers, a final humiliation that denied him even the mercy of communal mourning. The scholars who had supported him faced similar fates: some were imprisoned, others exiled to remote garrisons, still others executed quietly to avoid creating martyrs.

The second and third executions followed similar patterns, each targeting sons who had cultivated ties with influential jurists or charismatic saints in provinces distant from Meknes. Mawlāy Zaydān, despite being the son of Ismāʿīl's favored wife ʿĀ'isha al-Mubāraka, was strangled in 1120/1708 after his networks in Taroudant and the Sous were judged too dangerous. His crime was not military incompetence but political ambition dressed in religious garb. And later still, Mawlāy al-Ḥafīẓ, who had cultivated support among Qarawiyyīn scholars in Fez itself, was quietly poisoned before his conspiracy could mature. In each case, the sultan's response was surgical: the prince was eliminated, his clerical and saintly backers hunted down, and their networks dismantled. The executions served a pedagogical purpose—they announced to every scholar, every saint, every aspiring prince that the one unforgivable act was to combine royal blood with spiritual charisma. Separately, these forms of authority could be managed; together, they could fracture the empire.

Yet the very severity of these measures revealed an underlying dependency. If scholars and saints posed such mortal danger, it was because they retained the power to confer or withdraw legitimacy. Sultanic violence acknowledged what it sought to deny: that spiritual authority remained a currency the throne could suppress but never monopolize. Ismāʿīl could kill princes and exile scholars, but he could not rule without their prayers, their fatwas, their public endorsements. Every Friday sermon that named him as Commander of the Faithful, every legal ruling that upheld his decrees, every saint who refrained from denouncing his policies—these were negotiations, not givens. The throne's power was real but not absolute; it operated within a field of religious authority it could dominate but not erase.

Into this charged landscape of competing and overlapping sovereignties, Mawlāy ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz al-Dabbāgh emerged as a figure who defied every available category. He was born into an Idrisīd family of quiet distinction, his lineage tracing back through centuries to the founder of Fez itself. That ancestry granted him a prestige the ʿAlawīs could not ignore—to persecute an Idrisīd saint was to call into question one's own claim to sharifian legitimacy. Yet al-Dabbāgh leveraged none of the institutional possibilities his lineage afforded. He founded no zawiya, gathered no formal circle of disciples, sought no endowments or royal patronage. He worked as a weaver, his hands shaping wool and silk while his inner vision, he would later claim, encompassed celestial hierarchies. His authority, when it became known, derived not from textual mastery, but from what he described as direct, unmediated spiritual unveiling (kashf).

The claims attributed to him were of a kind that made both palace and madrasa uneasy, though for different reasons. He declared that the Dīwān al-Ṣāliḥīn was "gathered in my chest." If true, this located the spiritual administration of creation not in some inaccessible metaphysical realm, nor in the institutions of Fez or Meknes, but within the being of an illiterate craftsman. More provocatively still, he spoke of bearing multiple spiritual "robes" (ḥulal), each embodying a divine attribute of such overwhelming intensity that, were even one placed upon the city of Fez, its walls, its markets, its scholars, its multitudes would dissolve instantly into nonexistence. These were not the pieties of a conventional saint currying favor, nor the polemics of a rebel seeking to delegitimize the sultan. They were utterances that bypassed the entire architecture of political and religious authority, asserting a form of sovereignty that operated on a plane where neither throne nor Qarawiyyīn held jurisdiction.

For the palace, such claims were unsettling not because they directly challenged Mawlāy Ismāʿīl's rule—al-Dabbāgh made no political pronouncements, endorsed no rival claimants, built no networks of armed followers—but because they implied the irrelevance of sultanic authority. If ultimate governance resided in an invisible council that convened in a saint's chest, what did it matter who sat in Meknes? For the scholars of the Qarawiyyīn, the discomfort was different but no less acute. Al-Dabbāgh's authority derived from Muhammadan inheritance, not from legal training or textual transmission. He claimed to perceive realities—angelic hierarchies, the inner structure of prophethood, the mechanics of cosmic governance—that no amount of study could access. This was an implicit critique of the entire scholarly enterprise, suggesting that the highest forms of knowledge lay beyond the reach of those who had spent lifetimes mastering the transmitted sciences.

Yet neither palace nor madrasa moved against him. His Idrisīd lineage provided one layer of protection; the fact that he made no bid for institutional power provided another. But there was something else, harder to name—a sense, perhaps, that his claims, however audacious, operated in a register where coercion was beside the point. One could imprison a scholar, exile a rival saint, execute a rebellious prince. But how does one coerce someone who claims to contain the Dīwān? The very assertion created a kind of inviolability, not through strength but through sheer categorical incommensurability. Al-Dabbāgh's authority, if it existed, was of a kind that sultanic power could neither grant nor revoke.

This untouchability manifested concretely in an incident involving Aḥmad ibn al-Mubārak, then a scholar of grand standing in Fez. During Ismāʿīl's reign, the sultan dispatched a written command summoning Ibn al-Mubārak to Meknes to serve as imam at the newly constructed Jāmiʿ al-Riyāḍ in the elite quarter housing the regime's senior officials. Two of the sultan's men were sent as escorts, ensuring compliance. To refuse such a summons was to invite catastrophe—imprisonment, confiscation of property, exile, or execution. The historical record was filled with scholars who had disappeared for lesser acts of defiance. Ibn al-Mubārak understood the stakes. So did his father-in-law, the respected jurist Muḥammad ibn ʿUmar al-Sijilmāsī, the Imam of the Mosque of Mawlāy Idrīs in Zerhoun, who upon hearing that Ibn al-Mubārak had returned from Meknes without meeting the sultan, wrote in panic: "You departed without audience, without resolution. You cannot know what will now descend. You must return immediately, accept the appointment, demonstrate your willingness to serve."

This was the counsel of institutional religious authority navigating sultanic power through pragmatic accommodation. It was the voice of survival, learned through generations of scholars who had preserved their independence by knowing when to bend. But Ibn al-Mubārak had sought other counsel. When the summons first arrived, he had gone to al-Dabbāgh, consumed by dread. The saint's response was immediate and absolute: "Do not fear. If you travel to Meknes, we travel with you. But there will be no harm upon you, and what they request will not occur." Ibn al-Mubārak traveled to Meknes with the sultan's escorts, navigated whatever formalities were required, yet somehow avoided the audience and returned to Fez. When his father-in-law's urgent letter arrived, Ibn al-Mubārak returned to al-Dabbāgh with the message. The saint's response did not waver: "Remain in your house and fear no misfortune."

And nothing happened. No royal guards arrived to drag Ibn al-Mubārak back to Meknes. No order came for his arrest. No messenger delivered a reprimand. The matter simply dissolved, as if the sultan's will had encountered an invisible boundary and dissipated against it. The strangeness of this outcome was not lost on witnesses. One of Ibn al-Mubārak's associates in Meknes, astounded, later remarked: "We have seen nothing stranger than what you accomplished. The sultan sent you a written decree, reinforced it with his own hand, dispatched two officers to escort you—and you simply refused and returned home. And nothing befell you. This is beyond comprehension." The incident made no sense within the logic of sultanic authority. Mawlāy Ismāʿīl, who had executed his own sons for far less, who had destroyed zawiyas and ruined scholars, took no action against a man who had publicly ignored a direct royal command.

Thus, in a Morocco unified through the machinery of the Makhzan, legitimized through sharifian lineage, and governed through the uneasy partnership of throne and madrasa, al-Dabbāgh emerged as a third kind of authority—living proof that sovereignty possessed dimensions no sultan could map and no scholar could codify. His influence did not flow through fatwas, armed followings, or endowed institutions, but through the simple, inexplicable fact that when he said "remain in your house," those who heeded him were not harmed—even when defying the most powerful monarch Morocco had ever known.

4. The Scholar Who Crossed the Threshold

Before one can understand how al-Dabbāgh's voice penetrated the citadel of Fez, one must first understand the citadel itself. Al-Qarawiyyīn was not merely a mosque nor an academy; it was the oldest functioning university in the world, a sacred Idrisīd institution built beside the shrine of Mawlāy Idrīs II, and expanded over centuries by dynasties who saw in Fez the heart of the western Islamic world. Its origins were royal, not private. It was founded by the Idrisīd rulers when they built Fez itself, completed in 263/876 under Dāwūd ibn Idrīs II, as confirmed by the marble inscription once adorning the old miḥrāb and now preserved in Rabat. The Merinids transformed it into a full university: adding chairs of learning, endowed madrasas, vast libraries, astronomical clocks, gilded lamps, and hundreds of satellite mosques whose classrooms overflowed with students from Morocco, al-Andalus, and the Bilād al-Sūdān.

For all this, al-Qarawiyyīn was more than architecture. It was the guardian of Morocco’s Sunni intellect, a fortress of Mālikī orthodoxy whose legitimacy rested on its Idrisīd foundations. The sword of Imām Idrīs still crowns its minaret—a reminder that dynasties might rise and fall, yet the sacred authority of Fez flowed only through the House of Imām Idrīs. It was also the great filter of historical memory: while Idrisīd sources affirmed its royal foundation, later chroniclers—many shaped by anti-Idrisīd narratives—popularized the legend of Fāṭima al-Fihrī. Archaeological and epigraphic evidence restores the truth: al-Qarawiyyīn was an Idrisīd institution, tied to their capital, their shrine, and their vision for Morocco.

Long before al-Dabbāgh’s light appeared in Fez, another revolution had occurred far to the east, in a city whose fate shaped the entire Sunni world: Baghdad. It was here, amid the flames of sectarian conflict and the collapse of rational theology, that the Sunni curriculum took the form that would eventually penetrate al-Qarawiyyīn. By the 5th/11th century, the Abbasid Caliphate was weakened politically and overshadowed spiritually by the Fatimid Imamate of Cairo. The Muslim world stood divided between: Sunni Abbasids in Baghdad, Shi‘i Ismaili Fatimids in Egypt, and an intellectually fractured Muslim world.

The Abbasids, desperate to revive their legitimacy, turned toward a centralized intellectual project—one that would define, discipline, and unify Sunni identity. At the same time, Sunni thought was recovering from its own internal traumas: the collapse of Muʿtazilite rationalism under al-Mutawakkil (247/861); the rise of literalist traditionalism under Aḥmad ibn Ḥanbal (241/855); the decline of philosophical inquiry; and the triumph of ḥadīth-centric epistemology. Reason, which once nourished early Islamic philosophy, had been progressively curtailed, leaving the Sunni world intellectually disarmed in the face of Fatimid philosophical sophistication. Into this vacuum stepped a new architect.

The Seljuk vizier Niẓām al-Mulk (485/1092), perhaps the most influential statesman in medieval Islam, engineered a bureaucratic response: State-funded universities (al-madāris al-niẓāmiyya); a standardized Sunni curriculum; a chain of certified scholars; and institutional Sufism anchored to a Sunni shaykh. These schools were not neutral; they were explicitly designed to counter Fatimid Shi‘ism, independent Sufi circles, Muʿtazilite rationalism, and the philosophical tradition of Ibn Sīnā (428/1037) and al-Fārābī (339/950). Within their walls, a new Sunni identity was engineered—one that combined strict theology, ḥadīth, Shāfi‘ī jurisprudence, and a controlled form of Sufism. This curriculum was given its final shape by one man.

Al-Ghazālī (526/1111)—a direct student of al-Juwaynī (478/1085), who was elevated to the title Imām al-Ḥaramayn to consolidate Seljuk-Sunni authority—was himself granted the emblematic designation Ḥujjat al-Islām by Niẓām al-Mulk as part of the same legitimizing project. Though al-Juwaynī, his prestige provided the intellectual capital the system needed; al-Ghazālī, appointed to the Niẓāmiyya of Baghdad, transformed that capital into a coherent synthesis. In his work, he fused the three domains of Sunni thought into a single architecture: fiqh (outer law), Ashʿarī uṣūl and logic (method), and Taṣawwuf (inner purification). The synthesis was powerful—yet it imposed clear boundaries on what Sunni orthodoxy could become.

For in this integration, al-Ghazālī decisively redirected the trajectory of Sunni thought: he condemned the philosophers as heretical, dismissed key natural sciences—mathematics, physics, and cosmology—as spiritually perilous, dismantled the remaining pillars of Muʿtazilite rationalism, and marginalized traditions of critical inquiry, experimentation, and intellectual openness. He refashioned Sufism into an ethical discipline rather than a metaphysical exploration, and fused Sunni identity with a tightly regulated mystical ethos.

Thus, for all its sophistication, the Ghazālian framework embalmed Sunni intellectual life within a fixed architecture: a chain of teachers, a chain of certificates, a chain of orders, a chain of lodges, a chain of obedience, and finally a chain of imitation — all converging upon a Sunni shaykh who functioned as a Sunni imām. It was an elegant system, but a closed one: self-replicating, self-policing, and designed to reproduce a single orthodoxy rather than to cultivate new horizons of thought.

This was the “Sacred Sunni Madhhab”—distinct from the strict Almoravid Mālikī tradition and from the Mahdist doctrine of the Almohads, whose founder Ibn Tūmart (524/1130) is said to have studied under al-Ghazālī himself. It was a Baghdad-born orthodoxy disseminated through the Niẓāmiyya institutions: not a Maghribī creation, but a meticulously exported Seljuk-Sunni project.

Its shortcomings were clear to later observers: It froze intellectual movement. It prioritized transmission over inquiry. It condemned philosophical sciences as dangerous. It replaced creative thought with curated orthodoxy. Yet despite these limitations, the Ghazālian program conquered the Muslim world: from Baghdad to Nishapur, from Cairo to Damascus—and finally, to Fez.

“Look at this still, abiding light within the essence that holds it — the light in my outward form and in my inward reality. Look at this immense good my essence has been given, by which the cosmos is sustained. For by this light, all worlds are purified of evil. Every good in the heavens, the earth, and all realms flows from this light in my essence.” [Ibn al-Mubārak later wrote: “In that moment he spoke to me in a manner that revealed he was the one through whom the worlds are governed].”

It was here — not in argument, nor in books, nor in the disciplined logic of the Niẓāmiyya — that the scholar’s world shifted. The man formed by Baghdad’s triangular curriculum met a light that refused to be measured by syllogisms or uṣūl. From that moment, as he writes in Al-Ibrīz: “I heard from him knowledge I had never heard from any human being nor seen in any book.” This was the moment of surrender — the moment when the universe bent around a saint who had never studied a page.

The scholar was conquered—not by argument, but by the light of al-ʿilm al-ladun. What began as curiosity became astonishment. What began as astonishment became surrender. Al-Dabbāgh solved for him, without studies or books, the most arcane puzzles of Qur’anic sciences: the opening letters (ḥurūf al-muqaṭṭa‘āt), the ḥadīth of the Seven Letters, the inner meanings of Divine Names, the spiritual ontology of prophets and messengers.

To understand the magnitude of this surrender, one must recall who Ibn al-Mubārak was. His cousin and first teacher, Abū al-ʿAbbās Aḥmad ibn Muḥammad al-Ḥabīb al-Ghumārī (d. 1165 AH), was a renowned Sufi master of Sijilmāsa. Yet Ibn al-Mubārak himself was a prodigy of the rational and transmitted sciences. His biographers testify: “A master of logic, rhetoric, uṣūl, ḥadīth, qirāʾāt, tafsīr.” “A mujtahid muṭlaq who declared his own capacity for independent reasoning.” “A scholar whose grasp of ‘illa and qiyās exceeded his peers.” “In speed of memorization and precision he had no equal.” His classroom produced giants: Ibn Sūda, Ibn ʿAzzūz, al-Bannānī, al-Hilālī, al-Wurshānī, and many others who shaped 18th-century Moroccan scholarship and politics.

This brilliance, however, provoked resentment. Some traditional Malikis attacked him, especially when he revived the study of uṣūl and challenged idle taqlīd. The historian Ibn Zaydān even claimed Sultan Sīdī Muḥammad ibn ʿAbd Allāh (r. 1171-1204 / 1757-1790) would not accept his testimony—an accusation rooted not in piety but in rivalry. Yet through all this, Ibn al-Mubārak had already crossed another threshold: the scholarly mastery of the entire Baghdadian triangular system. He was the embodiment of Ghazālian Sunni orthodoxy in its most rigorous Moroccan form.

When Ibn al-Mubārak attached himself to al-Dabbāgh, Fez changed. The Qarawiyyīn, fortress of Malikī-Ghazālian orthodoxy, found one of its greatest jurists carrying the words of a man who had never held a book. The Idrisīd shrine beside the university bore witness to the meeting of two galaxies: the rational, systematized Sunni curriculum of Baghdad, and the raw, cosmic spirituality of the Moroccan saint. No zawiya, no lineage, and no political faction had achieved what this alliance achieved. This was not discipleship. This was penetration—the moment a saint born in the alleys entered the halls of the world’s oldest university, carried by the scholar formed in its logic. And Moroccan Sufism was never the same again.

Al-Ibrīz became the vessel of this transformation: a work in which the cosmic unveilings of an illiterate saint were disciplined, structured, and immortalized by the very man who would later become Fez’s shaykh al-jamāʿa. It marks the moment when ʿilm al-ladunī entered written scholarship, when the alleyway reached the university, and when the Idrisīd city absorbed a new current of sanctity. Through the hand of Aḥmad ibn al-Mubārak, the light of al-Dabbāgh crossed the threshold of al-Qarawiyyīn—turning a private encounter of kashf into one of the most enduring intellectual legacies of Moroccan Sufism.

5. From a Hidden Pole to Printed Classics

From the moment Ibn al-Mubārak recognized al-Dabbāgh’s station, love seized him with an annihilating intensity. He brushed aside the objections of jurists and the warnings of colleagues; no argument could detach him from the saint whose presence had overturned his inner world. Al-Dabbāgh’s affection met this devotion with equal depth, surrounding the jurist with a vigilance and intimacy that left no hour of day or night untouched. Al-Dabbāgh declared his unwavering presence to his disciple: "Hold me accountable before God if I do not attend to you five hundred times in a single hour!" and "I do not leave you night or day!" Ibn al-Mubārak reported a vision of their two selves in a single garment, a sign of their profound spiritual unity. The Shaykh confirmed the exclusivity of this bond, telling him: "You are my fortune and my portion; others are like the rest of the people to me!"

It was within this complete surrender of one heart to another that Al-Ibrīz Min Kalām Sayyidinā ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz al-Dabbāgh (“Pure Gold from the Words of our Master ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz al-Dabbāgh”) took shape. Authored with al-Dabbāgh's permission, Al-Ibrīz is more than a mere hagiography; it is a scholarly testimonial of the divine knowledge that flowed from the unlettered Shaykh. It stands as a critical work of Gnostic Jurisprudence (Fiqh 'Irfānī), using the analytical rigor of an Ijtihād-level scholar to systematically record and validate the secrets of a great saint, thereby immortalizing the Shaykh's spiritual station through the lens of academic verification.

Where al-Dabbāgh’s teachings were fluid, spontaneous, and overwhelmingly experiential, Ibn al-Mubārak imposed order: introductions, thematic chapters, logical divisions, and cross-references. He took a living torrent and set it into the channels of scholastic clarity. The book’s twelve chapters reflect this ambition. They move from prophetic sayings to cosmology, from the nature of the saintly hierarchy to the mysteries of creation, from the afterlife to the structure of paradise and hell. Each section captures a different aspect of the saint’s multidimensional teaching:

Chapter 1: Hadīth—Questions Posed by The Compiler, Answered through Unveiling.

Chapter 2: Qurʾān—Syriac Etymologies, Secrets of The Abbreviated Letters, Esoteric Exegesis.

Chapter 3: The Metaphysics of Spiritual Darkness.

Chapter 4: The Dīwān of The Saints and Its Unseen Operations.

Chapter 5: The Meaning of Taking a Shaykh and The Dynamics of Spiritual Will.

Chapter 6: The Inheritance of Earlier Shaykhs, The Transmission of Litanies, The Nature of Divine Names.

Chapter 7: Interpretations of Difficult Sayings By Earlier Masters.

Chapter 8: The Creation Of Adam, Human Form as The Summit Of Divine Artistry.

Chapter 9: Luminous and Dark Openings, The Difference Between Majdhūb And Fool, And Types Of Spiritual Illumination.

Chapter 10: The Barzakh and The Movement of Souls.

Chapter 11: The Structure of Paradise and Its Hierarchy.

Chapter 12: Descriptions of Hell and Its Metaphysical Realities.

Far from serving as a mere transmitter of his master's words, ibn al-Mubārak positions himself as a critical scholar and textual analyst. His methodology involves several distinctive features. First, he demonstrates particular concern for establishing correlations between al-Dabbagh’s statements and the opinions of jurists. This comparative approach serves a dual purpose: it validates the soundness of the master's pronouncements and highlights his remarkable rank in divinely-bestowed knowledge despite his ummiyya. Second, when transmitting his shaykh’s Quranic exegesis or derivations from prophetic traditions, the author follows a consistent pattern: he presents al-Dabbagh's interpretation, then subjects it to scrutiny by citing the opinions of eminent scholars, before ultimately defending and advocating for his master's position. He establishes himself as a rigorous critic and examiner of every opinion and statement, adding clarification and explanation that demonstrate correctness through both spiritual taste and rational proof.

The diversity of Al-Ibrīz’s source material reveals the breadth of this enterprise. Across its pages, Ibn al-Mubārak draws on hadith collections and their commentaries, works of uṣūl, manuals of fiqh, Sufi treatises, studies of Qurʾānic readings, and tafsīr. Quantitatively, he cites ninety-nine hadith-related works forty-eight times, forty-two citations from twenty-three works in uṣūl, thirty-nine citations from twenty-four juridical works, thirty-seven references from nineteen Sufi texts, twenty-two citations from eleven works on qirāʾāt, and eighteen citations drawn from five exegeses (tafsīr). In total, he engages 139 distinct works, producing 266 citations. Yet what matters truly is not only the quantity but the pattern. His hadith sources range from foundational compendia to specialized commentaries, including al-ʿAsqalānī, al-Nawawī, al-Suyūṭī and Ibn ʿAbd al-Barr. His work in legal theory shows particular depth, frequently invoking al-Ghazālī in disputes, alongside al-Juwaynī and al-Subkī. The text thus situates al-Dabbāgh’s words within a densely populated intellectual universe. The saint does not float above tradition; he speaks from within it, and the jurist ensures that every echo and resonance is audible.

A striking feature of ibn al-Mubārak's methodology concerns his treatment of Sufi topics. Despite the work's mystical content, he notably refrains from extensively supporting his master's statements with citations from earlier Sufi authorities. The major exception occurs in the sixth chapter on the spiritual guide (shaykh al-tarbiya), where he quotes from al-Suhrawardī's ʿAwārif al-Maʿārif while completing his commentary on verses that the Shaykh had not addressed. This selective citation pattern suggests ibn al-Mubārak's confidence in the self-authenticating nature of his master's inspired knowledge, requiring validation primarily through juridical and scriptural sources rather than mystical precedent.

A particularly striking feature of Ibn al-Mubārak’s method lies in his treatment of Sufi precedent. Despite the work’s mystical content, he is notably restrained in citing earlier Sufi masters as external support for his master. The major exception is the sixth chapter on the spiritual guide (shaykh al-tarbiya), where he draws on al-Suhrawardī’s ʿAwārif al-Maʿārif to complete commentary on verses the Shaykh had not addressed. This relative silence is deeply revealing. It suggests that Ibn al-Mubārak considered al-Dabbāgh’s inspired knowledge to be self-authenticating, needing validation primarily through juridical and scriptural sources rather than mystical quotation. The omission becomes a statement: Sufi authority here does not require a chain of Sufi texts; it requires alignment with Qurʾān, hadith, and the principles of fiqh.

Analysis of his citation patterns shows that Ibn al-Mubārak typically references each work only once or twice, with rare exceptions in discussions of foundational theological issues. This economy of citation signals a concern for concision and textual clarity. He is thorough without being verbose, dense without being burdensome. The effect on the reader is subtle: confidence in the author’s learning without exhaustion. The jurist’s erudition serves the saint’s presence rather than overshadowing it.

The most complex issue in studying Al-Ibrīz, however, is the multiplicity and variety of its titles. This is fundamentally rooted in the author's oversight in explicitly mentioning the title in the book's opening sermon (khuṭbat al-kitāb) or conclusion. This omission, which the author is criticized for, was the direct cause of the diverse names circulating for the same text. The proliferation of variant titles is not merely a technical bibliographic curiosity but reflects deeper questions about the work's intended nature and scope.

Three principal titles have dominated the manuscript tradition and modern editions, each encoding a distinct interpretive framework:

Al-Ibrīz min Kalām Sayyidinā ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz al-Dabbāgh ("Pure Gold from the Words of Our Master ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz al-Dabbāgh"): This formulation, appearing as the core element across nearly all versions, privileges orality and direct transmission. The term kalām (speech, discourse) positions the text explicitly as transcription—a written monument to oral teaching, emphasizing fidelity to the shaykh's actual utterances rather than biographical reconstruction or systematic theology.

Al-Dhahab Al-Ibriz fī Manāqib al-Shaykh ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz al-Dabbāgh (“The Purest Gold on the Narratives of our Master ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz al-Dabbāgh”): The substitution of manāqib (virtuous deeds, hagiographical narratives) fundamentally reorients the text toward the genre of saintly biography (sīra), foregrounding miraculous acts (karāmāt), exemplary conduct, and the construction of sanctity rather than doctrinal exposition.

Al-Tāj wal-Ibriz fī ʿUlūm Mawlānā ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz (The Crown and Pure Gold on the Sciences of our Master Abd al-Aziz): This version, adopted by the scholar al-Murābiṭī in Taysīr al-Mawāhib—the second major hagiographical work celebrating al-Dabbāgh's life—recasts the text as systematic knowledge (ʿulūm), presenting it as an organized repository of mystical sciences rather than spontaneous oral instruction or narrative biography. The addition of al-tāj (“the crown”) heightens the work’s honorific register, subtly aligning it with al-Dabbāgh’s third authority—the supra-scholarly rank poised between sainthood and political legitimacy—thus marking the text as the sovereign summit of Moroccan Sufism.

What decisively transforms this bibliographic puzzle into compelling historical testimony is the substantial body of elegiac and commemorative poetry composed by al-Murābiṭī and other disciples, which repeatedly and explicitly invokes the work's title, al-Tāj wa-al-Ibrīz.

Al-Murābiṭī, in his jīmiyya (rhyming in jīm), declares:

وَلَنَا قَدُّ الْعُلَمَاءِ نَجْلُ مُبَارَكِ * فِي التَّاجِ مَا يُشْفِي الصُّدُورَ وَمُثْلِجِ

And we have the foremost among scholars, the son of Mubārak,

In the Crown is what heals hearts and brings coolness.

In al-Shanqīṭī's zayniyya (rhyming in zayn), the title appears with even greater specificity:

مَنْ يُرْوَى وَيَرِدْ مَعَالِيهِ * يَنْظُرْ فِي التَّاجِ بِالحِجَا

Whoever seeks to drink and attain his lofty stations,

let him lookWith his discernment in the Book of the Crown and Pure Gold.

The jurist Muḥammad ibn al-Ḥasan al-Tāzī, in his elegy, celebrates the work's uniqueness:

كِتَابُ التَّاجِ وَالإِبْرِيزِ فِيهِ * هُدىً وَبُعْدٌ عَنْ طَرِيقِ الظَّلاَمْ

The Book of the Crown and Pure Gold—you will find in it

Guidance and distance from darkness.

Another poet invites readers to the text as a spiritual watering-place:

فَيَا ظَامِئًا مَنْهَلَ تَاجٍ بِرَبِّنَا * تَنَلْ مِنْهُ أَحْلَى مِنْ شَهَادَةِ وَالذِّكْرِ

O you who thirst—by God, come to the watering-place of the Crown,

You will obtain from it what is sweeter than honey and sugar.

The jurist Adawsh, in his rāʾiyya, provides critical testimony to Ibn al-Mubārak's scholarly credentials:

كَفَى شَاهِدًا عَدْلاً لَنَا ابْنُ مُبَارِكٍ * مُرَصِّعُ تَاجِ الْعِلْمِ مِنْ خَالِصِ التِّبْرِ

Sufficient for us as a just witness is Ibn Mubārak,

Who adorned the Crown of knowledge with Pure Gold.

The hypothesis that al-Tāj wa-al-Ibrīz represents Ibn al-Mubārak's original conception thus gains substantial evidentiary support. This poetic corpus—spanning multiple compositions and meters—provides contemporary witness to how the text circulated and was recognized within al-Dabbāgh's immediate community, strongly suggesting that Al-Ibrīz had achieved sufficient recognition to warrant formal literary commemoration, possibly indicating that drafts or completed sections were known to the shaykh's followers during his lifetime or immediately after his death in 1132/1720.

What remains certain is that this titular multiplicity, far from mere bibliographic confusion, opens a window onto the sociology of knowledge production in early modern Morocco: a text composed through oral dictation, transcribed across years of accumulated sessions, circulated in recognizable form among disciples who celebrated it in formal verse, yet transmitted through manuscripts that encoded competing interpretations of its essence—whether as faithful transcription, hagiographical narrative, or systematic exposition of mystical sciences. The poetic archive proves what the manuscripts obscure: that Al-Ibrīz, under whatever name, was recognized as extraordinary from its earliest circulation.

By the time Ibn al-Mubārak completed the final edition of al-Ibrīz in 1136/1724—four years after al-Dabbāgh’s passing—he was only forty-two years old. This date coincided with a critical phase of spiritual and intellectual resurgence in Morocco, granting the book immediate and unparalleled recognition. It enjoyed total acceptance among both the elite and the general public, and its reputation spread rapidly by travelers (tatāyarat bihi al-rukbān).

This widespread reception, achieved immediately upon its release from the scholarly and religious capital of Morocco, Fez, demonstrates that the city’s status as a global center for Mālikī jurisprudence and Sufi schools served as a multiplier for the text's authority. Emerging from the strict academic environment of the Idrisīd Presence, and overseen by a jurist like Ibn al-Mubārak , the text secured immediate diffusion and legitimacy within the network of scholars and saints across all regions.

The influence of Al-Ibrīz was such that it soon generated its own refined “political“ tradition. The Fāsī jurist Muḥammad b. ʿĀmir al-Muʿaddanī al-Tādilī (d. 1234/1819) produced an abridgment titled al-Qawl al-Wajīz fī Tahdhīb al-Ibrīz, composed at the request of the Salafī-leaning Sultan Mawlāy Sulaymān (r. 1206–1238/1792–1822). The work opens with a substantial four-part introduction, including an expanded biography of Ibn al-Mubārak. Its purpose was clear: the sultan had expressed concern over certain ecstatic utterances attributed to al-Dabbāgh, and he instructed al-Muʿaddanī to remove them in order to make the text more accessible—and less troubling—to a broader readership.

All of this—the love, the structure, the reception, the titles, the acceptance, the refinement—must be read together to understand what Al-Ibrīz does to its readers. It is not simply a book about a saint; it is a machine for producing a saintly image inside the reader’s imagination. The author writes as jurist, reporter, and storyteller at once. He frames scenes with the clarity of a novelist while maintaining the precision of a scholar. The effect is powerful: al-Dabbāgh becomes distant enough to be revered, close enough to be loved, miraculous without estrangement, simple yet inexhaustible. Through this weaving, the reader does not merely observe Sufism—he begins to inhabit its consciousness.

The index sketches a conceptual cartography—spiritual opening vs. withdrawal (salb), hidden vs. cultivated shaykhs, sincere vs. utilitarian disciples, luminous vs. dark veils, beneficial vs. harmful invocations, heavenly vs. infernal architectures—yet none of these axes circumscribe al-Dabbāgh himself. Rather than delimiting him, this map expands the points of entry into his figure, allowing the reader to approach his presence from multiple, unfolding angles. Each reader chooses, consciously or unconsciously, the aspect that resonates most deeply with his own state. One reader enters through the fear of death and discovers in the Shaykh a guide across the barzakh. Another approaches through the dilemma of true and false teachers and encounters in him a criterion of discernment. A young murīd arrives by way of the tales of companionship and sees in him the master he longs to meet. The same text, the same chapters—yet each unveils a different Dabbāgh.

Ibn al-Mubārak writes with this multiplicity in mind. He does not present a flat, unilinear portrait. Instead, he alternates between intimate scenes and cosmic teachings, between Fez as a concrete city and Fez as a spiritual axis, between small miracles and vast theophanies. He describes the Shaykh laughing, traveling, correcting, consoling, suffering, unveiling, and teaching. He allows al-Dabbāgh to speak of ascent (tara’qqī) in sainthood, in a tone that transforms abstract doctrine into inhabited worlds. He reports the Shaykh’s discourse on the types of visions, the marks distinguishing authentic unveiling from false imagination, the features separating a true spiritual guide from a false one. He lets the reader feel the terror of being stripped after a gift, and the mercy that can follow. At the same time, he warns him against sinking into the chronically recycled, folkloric conditions of sainthood that tradition often repeats, and prevents him from falling into the trap of karamāt-literature that fashions mythical, unreachable figures. Reading these passages, the seeker does not simply “learn” about the unseen; he feels brushed by it.

In this sense, Al-Ibrīz is a theatre of presence. The reader becomes one more companion sitting in the Shaykh’s circle, walking the streets of Fez at his side, listening to the currents that pass between master and disciple. The city itself becomes a vast zawiya and a field of inner combat, where perceptions are stripped and rebuilt. As the reader moves through these pages, he shares in Ahmad ibn al-Mubārak’s own awakenings—moments when the Shaykh redirects his gaze away from the glamour of saints and toward the stark truth that love accepts no rivals, that a single heart can be a full portion, and that the seeker brings nothing but receptivity. These subtle disclosures accumulate not as anecdotes but as shifts in awareness, teaching the reader how Sufi knowledge settles into memory: quietly, decisively, and without spectacle.

Because of this, Al-Ibrīz never stabilizes into a single, definitive image. It remains permanently re-readable. The reader who returns to it after years finds a different book, not because the ink has changed, but because his inner state has changed. New chapters come to the foreground; new episodes strike the heart; old stories take on darker or brighter hues. A young disciple recognizes himself in the eager murīd whose questions stumble into wisdom; an older seeker recognizes himself in the one who undergoes salb after fatḥ. The Shaykh remains the same; the reader does not. The book’s narrative philosophy is precisely to exploit this changing subjectivity, to ensure that al-Dabbāgh is never reduced to a fixed icon. He is always a presence in motion.