The Dabbagh Family of Morocco: Twelve Centuries of Sharīfian Authority

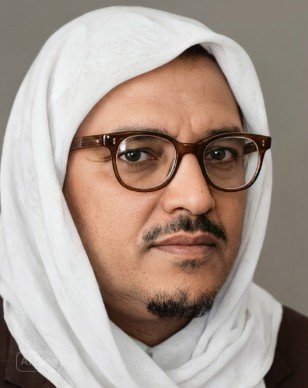

In the 13th/19th century, the Fāsī scholar and mystic Muḥammad ibn ʿAbd al-Ḥadīdh al-Dabbāgh (d. 1291/1874), known as Abū Ṭarbūsh, reported a vision that crystallized his family's self-understanding. As recorded by ʿAbd al-Ḥayy al-Kattānī in al-Maẓāhir al-Samiyya, Abū Ṭarbūsh encountered his Grandfather, the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ, in daylight, near Wādī al-Shurafāʾ in Fez. The Prophet ﷺ commanded him to accompany him to Rāʾs al-Jinān Gate, where they found a great quantity of the finest white flour. When asked his opinion of its quality, Abū Ṭarbūsh confirmed it was of the finest kind. The Prophet ﷺ then declared that the Dabbaghs were the best of his progeny.

This vision, with its imagery of pure white flour symbolizing untainted genealogy and its setting at the Gate of Gardens evoking proximity to Paradise, encapsulates the complex interplay of genealogical authentication, mystical experience, and social authority that characterized the Dabbagh family across twelve centuries. The family was neither the only nor necessarily the most powerful Idrisid lineage in Morocco—they shared Fez's sharīfian landscape with the Jūṭīs (who briefly ruled as sultans). Yet the Dabbaghs achieved a particular form of recognition that allowed them to maintain prominence from Marinid patronage through colonial occupation to the present ʿAlawī period.

“The Dabbagh sharifs bear the title “the Golden Chain” (silsilat al-dhahab), for their noble lineage stands confirmed by the unanimous consensus of the genealogists, transmitted through tawātur.”

This study examines how the Dabbaghs constructed what might be termed an infrastructure of legitimacy: a multi-layered system combining genealogical documentation, economic foundations, spatial positioning, institutional distribution, and continuous charismatic renewal. The family understood that sharīfian distinction required ongoing investment across generations. They accumulated documentary validation transforming their nasab from contested claim into scholarly consensus. They secured economic independence through royal endowments. They concentrated presence in specific urban quarters and controlled pilgrimage sites, creating spatial infrastructure making their baraka accessible. They positioned family members across multiple institutional domains simultaneously, creating redundancy protecting against individual failures. Most importantly, they produced recognized saints across generations, demonstrating that inherited charisma was renewable rather than depleting.

The analysis proceeds chronologically, tracing the family from their origins as descendants of ʿĪsā al-Anwar ibn Idrīs II through their Andalusian period to their settlement in Morocco and contemporary dispersal across Morocco and the Arabian Peninsula.

1. The Genealogical Foundation: From ʿĪsā ibn Idrīs to Granada

All sharīfian authority originates in the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ, through his daughter Fāṭima and her husband ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib, and through their son al-Ḥasan ibn ʿAlī. The Quranic command to show love to the Prophet's family (42:23) established theological foundation that would shape political and social structures across Islamic history.The Ḥasanid lineage reached Morocco through Idrīs ibn ʿAbd Allāh ibn al-Ḥasan ibn al-Ḥasan, known as Mawlāy Idrīs al-Akbar (the Elder/the Greater). He fled to the Maghrib following the failed Ḥasanid uprising at Fakhkh in 169/786, finding refuge among the Awraba Berbers. Between 172-177 AH/788-793 CE, he founded Fez and established an independent Islamic state before being assassinated by ʿAbbāsid agents in 177/793.

His son Idrīs II, known as Mawlāy Idrīs al-Azhar (the Radiant), born after his father's death and raised by his mother Kanza bint Isḥāq and the guardian Rāshid, expanded Fez and consolidated Idrisid authority. In 192/808, he built al-ʿĀliyya on the western bank of Wādī al-Jawāhir, creating a twin-city structure. When he was assassinated in 213/828—again by ʿAbbāsid poison—he left twelve sons.

Among the twelve sons of Mawlāy Idrīs II was ʿĪsā al-Anwar (the Luminous), from whom the Dabbagh family descends. Following their father's death, Kanza bint Isḥāq implemented a strategic dispersion, assigning each grandson a different region to prevent the concentration that had made assassination so effective. ʿĪsā received governance of Tadla and surrounding territories in central Morocco, with his capital at Āyit ʿIṭṭāb.

ʿĪsā functioned as an autonomous amir exercising full sovereign powers. He minted silver dirhams bearing his name and Idrisid claims to authority—numismatic evidence from Wazzaqur mint in 225/840 survives. He administered justice, maintained military forces, and governed his territories as an Idrisid prince. Control of the silver mines at Jabal ʿAwwām and surrounding areas gave him command over the raw material essential for coinage, making his territories economically vital to Idrisid legitimacy.

When ʿĪsā's brother Muḥammad, ruling from Fez with nominal authority over his siblings, attempted to monopolize minting rights, ʿĪsā refused subordination and struck his own coins. Military confrontation followed. ʿĪsā was defeated at Wādī al-ʿAbīd but withdrew strategically into the interior rather than surrendering. When both Muḥammad and his brother ʿUmar were assassinated in 221/836, ʿĪsā re-emerged, restored his emirate, and expanded southward. Numismatic evidence demonstrates that between 266/880 and 279/893, descendants of ʿĪsā controlled Fez itself, with coins struck there bearing names from his branch.

Isāwi Dirham

Silver dirham issued under Imām'Isa ibn Idris al-Anwar at Wazzaqur mint in 225/840.

From ʿĪsā al-Anwar descended numerous Idrisid lineages, including the Manalis (Zabadis), Buzidis, ʿAmmuris, and others. What would distinguish the Dabbagh branch from these related families was not descent itself—which was widely shared—but later accumulation of scholarly achievement, mystical authority, royal recognition, and institutional positioning.

Following the eventual collapse of centralized Idrisid political authority in the late 3rd/9th and early 4th/10th centuries, descendants of ʿĪsā al-Anwar dispersed across Morocco. The ancestors of the Dabbagh family established themselves in Sabta, the strategic port controlling the southern shore of the Strait of Gibraltar.

Sabta functioned as cosmopolitan entrepôt connecting al-Andalus, the Maghrib, and Mediterranean trade networks. For an Idrisid family stripped of political power, the city offered opportunity to rebuild social position through scholarship and commerce. Sabta's sharif community provided marriage partners preserving genealogical consciousness, while its urban environment maintained connection to learning that might have been lost through rural dispersal. Most importantly, Sabta's proximity to al-Andalus created possibilities for the trans-Mediterranean migration that would define the next chapter of family history.

2. The Andalusian Period: Scholarship and Service in Granada

In 479/1086, the Almoravid sultan Yūsuf ibn Tāshfīn prepared to cross the Strait to wage jihad against Christian kingdoms advancing across Iberia. Ibn Tāshfīn commanded an empire from Senegal to Zaragoza, yet he would not wage war without an Idrisid sharif at his side. The sources specify his intention: bi-qaṣd al-tabarruk bihi—for seeking blessing through him.

The sharif was Abū al-Ḥasan ʿAlī ibn ʿAbd al-Raḥmān al-Dākhil, whose title commemorated his crossing into al-Andalus and distinguished him as founder of the family's Iberian presence. His genealogy traced through ʿĪsā ibn Aḥmad ibn Muḥammad ibn ʿĪsā ibn Idrīs, connecting him to the Tadla imamate. This moment reveals fundamental structures: even a sultan commanding vast military power understood warfare as requiring spiritual dimension, accessed through proximity to the Prophet's descendants. The sharif's presence transformed military campaign into worship, his baraka flowing into the army.

“Their ancestor, ʿAlī ibn ʿAbd al-Raḥmān ibn ʿĪsā ibn Aḥmad ibn Muḥammad ibn ʿĪsā ibn Idrīs, settled in Granada in 479/1086 during the reign of Yūsuf ibn Tāshfīn al-Lamtūnī.”

Abū al-Ḥasan ʿAlī's crossing represented strategic repositioning from Maghribi marginality to Andalusian centrality. Where the family had lost political authority in Morocco, they might recover social standing in al-Andalus through genealogical distinction combined with scholarly achievement.

Following the Almoravid campaigns, Abū al-Ḥasan ʿAlī settled in Granada. The family's establishment was not as desperate refugees but as honored migrants whose sharif status immediately positioned them within Granada's elite. Granada under Nasrid rule became one of al-Andalus's premier centers of Islamic civilization.

The family pursued clear strategy: convert genealogical capital into scholarly credentials. They used sharīfian status to access educational opportunities while demonstrating competence justifying authority independent of bloodline. This dual foundation—noble descent validated by scholarly achievement—characterized their approach across generations.

The Andalusian trajectory reached its apex in Abū al-Qāsim Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad al-Sharīf al-Gharnāṭī (d. 760/1359), who served as chief judge of Granada under Nasrid sultans Abū al-Ḥajjāj Yūsuf I (d. 755/1354) and Muḥammad V (d. 793/1391). Al-Sharīf was among the preeminent scholars of his age, recognized for mastery across grammar, Quranic exegesis, legal theory, prosody, and rhetoric.

“Among them was our master the sharīf Abū al-Qāsim al-Gharnāṭī, namely Sīdī Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad ibn ʿAlī ibn Aḥmad ibn Hārūn ibn Shaykh Sīdī Muḥammad known as Kannūn ibn ʿAbd Allāh known as Mindīl ibn ʿAlī ibn Abī Zayd ʿAbd al-Raḥmān ibn ʿĪsā ibn Aḥmad ibn Aḥmad ibn ʿAlī ibn ʿĪsā ibn Idrīs ibn Idrīs.”

His students shaped Islamic thought for generations: Ibrāhīm ibn Mūsā al-Shāṭibī (d. 790/1388), author of foundational work on higher objectives of Islamic law (al-Muwāfaqāt); Muḥammad ibn Juzayy (d. 757/1356), Quranic commentator; Ibn Zamrak (d. 793/1390), court poet whose verses adorn the Alhambra; Aḥmad ibn Qunfudh (d. 810/1407), biographer; and Ibn al-Khaṭīb himself.

Ibn al-Khaṭīb, the famous Marinid and Nasrid vizier and historian, described Abū al-Qāsim as unique in his generation, surpassing others in dignity, nobility, mastery of linguistic sciences, judicial authority, and eloquence. Ibn Khaldūn, the foundational historical theorist, studied under him and called him "the master of the world in majesty, dignity, and leadership, and the imam of language."

Abū al-Qāsim’s noble lineage commanded such recognition in Granada that even Abū al-Ḥasan ʿAlī ibn al-Jayyāb (d. 749/1348), the emirate's chief secretary and one of al-Andalus's foremost poets, celebrated it publicly. When congratulating him on the birth of a child, Ibn al-Jayyāb composed verses honoring the prophetic descent:

Welcome to a descendant of the Banū Hāshim,

From glory's tree he traces his noble line,

And hail to the son of the Imam who,

Struck down Marḥab on Khaybar's day.

However, Ibn al-Khaṭīb made an error, tracing him to Muḥammad ibn al-Ḥasan ibn ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib—a line genealogists unanimously agree produced no descendants. Later genealogists like al-Faḍīlī al-ʿAlawī in al-Durar al-Bahiyya had to correct this mistake: “No attention should be given to what Ibn al-Khaṭīb mentioned when tracing the lineage of al-Sharīf al-Gharnāṭī to Muḥammad ibn al-Ḥasan ibn ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib, for the genealogists are unanimous that he left no descendants. Nor should attention be given to those who traced his lineage through Yaḥyā al-Jūṭī, for this is clear error, as a group of authoritative imams have explicitly stated.”

Al-Sharīf served diplomatically as well. In 757/1356, he led an embassy to Marin sultan Abū ʿInān in Fez, mediating a delicate situation. His mission succeeded, demonstrating how sharīfian identity transcended particular polities, creating authority that different Muslim rulers recognized even when political interests conflicted.

His literary production demonstrated scholarly range: Rafʿ al-Ḥujub al-Masṭūra (commentary on Ḥāzim's Maqṣūra), Sharḥ al-Qaṣīda al-Khazrajiyya (on prosody, becoming standard reference), al-Taqyīd al-Jalīl (grammar commentary), al-Durra al-Naḥwiyya (on elementary grammar), and Sharḥ al-Tanbīh (Shāfiʿī jurisprudence).

His grandeur in Granada provoked envy, particularly among Sabta's scholarly elite who resented his prominence. In verses defending his position, he wrote:

In al-Andalus I shelter in a wing,

Spacious for glory, shade spreading wide for eminence,

In splendid Granada I settled,

Safe from time's vicissitudes in sanctuary,

Not like another place where dwellings emptied, tribes grew distant,

And glory's covenant was betrayed,

Its haunts denied me, though I was known,

Only through my people [the Dabbaghs] in former days,

Were it not for the tents of the Prophet's Family there,

What nobility and generosity they possess!

And youths from the descendants of al-Zahrāʾ, generous souls,

Commanding loyalty and mercy,

I would say: may no rain cloud ever water it,

Save poison's dregs or fresh-spilled blood,

Let no tear fall upon it from grief,

Nor teeth gnash from regret,

What harm if my homeland cast me out or grew distant?

Mine is the honor of al-Baṭḥāʾ and the Sacred Precinct.

“The shaykh of the age in majesty, dignity, and leadership; the master of eloquence in weaving both verse and prose.”

His son Abū al-Maʿālī al-Ṭayyib succeeded him as chief judge, demonstrating successful intergenerational reproduction of elite status through combined genealogical and scholarly capital.After several centuries of establishment in Granada, where they had achieved the highest levels of scholarly and judicial distinction, the family faced the decision to return to Morocco. The first to make this reverse migration was Abū al-ʿAbbās Aḥmad ibn Abī al-Qāsim Muḥammad ibn Ibrāhīm ibn ʿUmar, known as al-Qādim (the one who came), who arrived in Sala (Salé) in 790/1388.

This migration came not as refugee flight—Granada would not fall to Christian forces until 897/1492, more than a century later—but as strategic repositioning. The family had observed political instability in Granada, where succession disputes among Nasrid princes periodically disrupted the kingdom. Meanwhile, the Marinid dynasty in Morocco actively sought to attract Andalusian scholars and sharifs, offering patronage and positions to enhance their own legitimacy.

3. Migration and Marinid Patronage: Settlement in Salé and Return to Fez

Aḥmad ibn Abī al-Qāsim al-Qādim's arrival in Salé was facilitated by Marinid sultanic patronage, specifically that of Abū al-ʿAbbās Aḥmad ibn Sālim al-Mustanṣir billāh, who ruled from 760/1359 to 796/1393. The sultan received Aḥmad with extraordinary honor, providing substantial stipends from the royal treasury in recognition of his noble lineage and his family's distinguished service to the Nasrid dynasty. The Marinids and Nasrids competed for elite talent, with figures like Ibn al-Khaṭīb and Ibn Khaldūn moving between the two courts. The Marinids, having displaced the Almohads whose authority rested on Mahdist claims, actively sought sharīfian support to legitimate their rule.

This royal patronage was not merely charitable gesture but calculated political investment. The Marinids, despite their military success in unifying Morocco, lacked the genealogical distinction that Islamic political culture increasingly valued. Supporting sharīfian families allowed them to demonstrate piety, access baraka through association with the Prophet's ﷺ descendants, and create networks of obligation with families whose religious authority complemented Marinid temporal power. A sharīf from Granada's judicial elite—descendant of the kingdom's chief judge and from the family that had taught Ibn al-Khaṭīb himself—offered valuable symbolic capital, demonstrating that prophetic descendants recognized Marinid authority.

The specific form of Marinid support proved crucial for the family's long-term establishment. Rather than providing one-time gifts or irregular stipends dependent on sultanic favor, the Marinids granted the Dabbaghs permanent revenue rights from the Dār al-Dabbāgh, the state-controlled tanning facility in Salé. A royal decree dated 790/1388 formalized this arrangement, assigning them regular payments from the tanning house's tax revenues. This endowment provided economic independence, freeing the family from dependence on teaching fees, judicial salaries, or commercial ventures while creating institutional continuity that would survive individual sultans' deaths and dynastic transitions.

The administrative designation became their surname. The genealogist ʿAbd al-Salām al-Qādirī al-Ḥasanī (d. 1110/1698) clarified in al-Durr al-Sanī li-man bi-Fās min Ahl al-Nasab al-Ḥasanī wa-l-Ḥusaynī: “They were never known to practice the tanning craft. Rather, the reason for the name [Dabbagh] is what I found in a decree they still possess, dated 790/1388, ordering that their stipend be drawn from the revenue of the Dār al-Dabbāgh in Salé when they resided there. Thus the name derived from the intensive form of dabgh (tanning) on account of that.”

The revenue assignment from the tanning house had an unintended consequence that would permanently mark the family's identity. Despite never practicing the trade of leather-working themselves, their association with the Dār al-Dabbāgh led to their designation as "al-Dabbāgh," initially as administrative notation indicating their revenue source but eventually crystallizing as family surname. The nisba transformed from bureaucratic label to genealogical marker, a process the family initially resisted as demeaning to their sharīfian dignity. The etymological issue troubled later family members sufficiently that genealogists felt compelled to clarify that the name derived not from actual craft practice, considered inappropriate for sharifs, but from revenue administration, an acceptable form of economic engagement.

“Among the sharifs I met in Salé when I visited the city seeking baraka an ziyāra were the ʿĪsāwī sharifs, descendants of Shaykh ʿUmar al-Dabbāgh ibn ʿAbd al-Raḥīm ibn ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz ibn Abī ʿAbd Allāh Hārūn. Sayyid ʿUmar had two sons: Ibrāhīm and Muḥammad.”

The family's migration from Salé to Fez occurred in the opening years of the 9th/15th century, as documented in surviving royal decrees. This relocation represented more than change of residence; it constituted symbolic and practical reclamation of their Idrisid heritage. Fez was not merely Morocco's largest city and intellectual capital but the ancient foundation of Idrīs al-Akbar and Idrīs al-Azhar, the sacred geography from which Idrisid authority had originally emanated. For descendants of ʿĪsā ibn Idrīs, returning to Fez meant returning to the city their ancestor's father had built and ruled, reactivating genealogical connections dormant during centuries of Andalusian residence.

The Dabbaghs settled specifically in Ḥūmat al-ʿUyūn, the "Quarter of Springs", the old city on the Qarawiyyīn side of the Wādī Fās. This neighborhood became known as a sharīfian enclave, densely populated by various Idrisid families who created a concentrated geography of baraka in the heart of Fez. Spatial proximity facilitated marriage alliances, collective assertion of sharīfian privileges, mutual authentication of genealogical claims, and coordination of political strategies vis-à-vis ruling authorities. The first Dabbagh residence in Fez, located at ʿAyn al-Baghl within the ʿUyūn quarter, remained in family possession for centuries, serving as symbolic anchor of their Fāsī presence even as various branches established additional properties elsewhere in the city.

The timing of the Dabbagh return to Fez coincided with broader movements of Idrisid families reestablishing themselves in their ancestral capital. Genealogists noted that the Dabbaghs were among the first Idrisid sharīfs to return to Fez after the long period of dispersion that followed the collapse of Idrisid political authority in the 4th/10th century. Their early return gave them temporal precedence in reoccupying sharīfian space and positioned them advantageously for claiming endowment rights, administrative positions, and social recognition as the 9th/15th century progressed.

The revenue assignment from the tanning house had an unintended consequence that would permanently mark the family's identity. Despite never practicing the trade of leather-working themselves, their association with the Dār al-Dabbāgh led to their designation as "al-Dabbāgh," initially as administrative notation indicating their revenue source but eventually crystallizing as family surname. The nisba transformed from bureaucratic label to genealogical marker, a process the family initially resisted as demeaning to their sharīfian dignity. The etymological issue troubled later family members sufficiently that genealogists felt compelled to clarify that the name derived not from actual craft practice, considered inappropriate for sharifs, but from revenue administration, an acceptable form of economic engagement.

The family's migration from Salé to Fez occurred in the opening years of the 9th/15th century, as documented in surviving royal decrees. This relocation represented more than change of residence; it constituted symbolic and practical reclamation of their Idrisid heritage. Fez was not merely Morocco's largest city and intellectual capital but the ancient foundation of Idrīs al-Akbar and Idrīs al-Azhar, the sacred geography from which Idrisid authority had originally emanated. For descendants of ʿĪsā al-Anwar ibn Idrīs al-Azhar, returning to Fez meant returning to the city their ancestor's father had built and ruled, reactivating genealogical connections dormant during centuries of Andalusian residence.

The Dabbaghs settled specifically in Ḥūmat al-ʿUyūn, the "Quarter of Springs", the old city on the Qarawiyyīn side of the Wādī Fās. This neighborhood became known as a sharīfian enclave, densely populated by various Idrisid families who created a concentrated geography of baraka in the heart of Fez. Spatial proximity facilitated marriage alliances, collective assertion of sharīfian privileges, mutual authentication of genealogical claims, and coordination of political strategies vis-à-vis ruling authorities. The first Dabbagh residence in Fez, located at ʿAyn al-Baghl within the ʿUyūn quarter, remained in family possession for centuries, serving as symbolic anchor of their Fāsī presence even as various branches established additional properties elsewhere in the city.

The timing of the Dabbagh return to Fez coincided with broader movements of Idrisid families reestablishing themselves in their ancestral capital. Genealogists noted that the Dabbaghs were among the first Idrisid sharīfs to return to Fez after the long period of dispersion that followed the collapse of Idrisid political authority in the 4th/10th century. Their early return gave them temporal precedence in reoccupying sharīfian space and positioned them advantageously for claiming endowment rights, administrative positions, and social recognition as the 9th/15th century progressed.

“The house of the Dabbāghs in Fez possesses renown and clarity in sharīfian lineage, and authenticity in the exalted Idrīsid branch.”

The family's establishment in Fez created foundation for the institutional density they would develop over subsequent centuries. Proximity to the Qarawiyyīn mosque-university, Morocco's premier center of Islamic learning, provided educational opportunities for family members and teaching positions for qualified scholars. The concentration of sharīfian families in adjacent quarters created marriage markets that allowed preservation of genealogical purity through endogamous alliances while building networks of kinship that crosscut different Idrisid branches. Access to royal courts created opportunities for judicial appointments, diplomatic service, and accumulation of patronage.

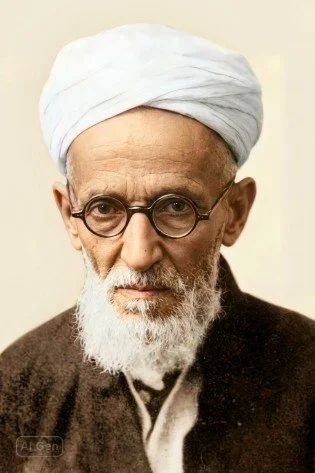

4. Mawlay ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz: From Scholarship to Sanctity

The transformation of the Dabbagh family from respected sharīfs into custodians of living charisma occurred through Abū Fāris ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz ibn Masʿūd al-Dabbāgh (d. 1131/1719), whose mystical teachings, recorded by his disciple Aḥmad ibn al-Mubārak in al-Ibrīz min Kalām Sayyidī ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz al-Dabbāgh, transformed how Moroccan Islam understood the relationship between prophetic lineage and spiritual knowledge. The text became one of the Maghreb's most widely circulated mystical works, studied from Fez to Timbuktu to Cairo, ensuring that the Dabbagh name would be permanently associated with Sufi sanctity and esoteric knowledge.

Mawlay ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz's spiritual authority, as presented in al-Ibrīz, combined several elements that proved revolutionary for Moroccan Sufism. His mystical knowledge was characterized as direct divine bestowal (fatḥ) rather than acquisition through human teachers, positioning him as recipient of unmediated illumination from God. He claimed no shaykh in the conventional sense, instead attributing his initiation to al-Khiḍr—the mysterious prophetic figure who in Islamic tradition serves as guide to those whom God chooses to teach directly.

This claim to Khiḍrian initiation was not unprecedented in Islamic mysticism, but Mawlay ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz articulated it with unusual specificity and theological sophistication. He described the mechanics of spiritual unveiling (kashf), the hierarchies of sainthood (wilāya), and the cosmic functions of prophets and saints in language that combined Sufi metaphysics with accessible narrative. His teachings emphasized that prophetic descent itself constituted not merely social distinction but metaphysical reality with implications for spiritual capacity and divine favor. This theological validation of sharīfian status had profound implications: it suggested that genealogical connection to the Prophet ﷺ created predisposition toward spiritual realization, though it did not guarantee it without personal effort and divine grace.

Al-Ibrīz presented detailed visions of the unseen world—descriptions of paradise, hell, the spiritual hierarchy of saints, and cosmic realities beyond ordinary perception. These were not abstract theological speculations but concrete descriptions claiming direct visionary access. Mawlay ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz described encountering the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ in visions, conversing with him, receiving instruction from him, and witnessing realities of the barzakh (the intermediate realm between death and resurrection).

The text addressed questions that troubled Moroccan Islam: How do saints know what they know? What is the relationship between Islamic law (sharīʿa) and mystical realization (ḥaqīqa)? Can prophetic guidance continue after the Prophet's ﷺ death? How should Muslims understand the intercession (tawassul) sought from saints and the Prophet's ﷺ family? Mawlay ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz's answers to these questions, grounded in claimed direct experience rather than mere textual interpretation, provided framework that would shape Moroccan religious culture for generations.

His explanation of baraka proved particularly influential. He argued that baraka was not metaphorical concept but real spiritual substance that flowed through prophetic lineage, accumulated in saints' bodies and tombs, and could be transmitted through physical contact, proximity, and devotional practices. This materialization of spiritual authority validated practices already widespread in Moroccan Islam—tomb visitation, seeking blessings from sharīfs, touching sacred objects—while providing them with sophisticated theological justification.

Al-Ibrīz achieved extraordinary circulation within decades of its composition. Manuscripts multiplied across Morocco and beyond, studied in Sufi lodges, taught in madrasas, copied by students seeking spiritual advancement. The text's accessibility proved crucial to its success: while containing sophisticated metaphysical doctrines, it was structured as dialogues between master and disciple, making complex ideas comprehensible to readers without advanced theological training.

The text influenced subsequent Moroccan Sufi authors profoundly. Later shaykhs cited al-Ibrīz as authoritative reference on contested questions of mystical doctrine. Aḥmad ibn ʿAjība (d. 1224/1809), whose own mystical writings would become influential, engaged extensively with Mawlay ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz's teachings. Mawlay ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz's explanations of spiritual stations, the nature of sainthood, and the relationship between sharīʿa and ḥaqīqa became standard reference points in Maghribī mystical discourse.

“The blessed sharīf Abū Fāris Mawlay ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz ibn Masʿūd al-Dabbāgh... Their house in Fez enjoys wide renown. Our master, the learned ḥāfiẓ Sīdī Aḥmad ibn al-Mubārak al-Lamṭī al-Sijilmāsī, composed his biography describing him with the loftiest attributes of divine knowledge, recounting marvels of spiritual unveiling and prophetic mysteries in a work titled al-Ibrīz fī Manāqib al-Shaykh ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz, filling an entire volume with extravagant praise of his sanctity. The book claims al-Dabbāgh received knowledge from teachers unknown to any of us—neither we nor anyone in our time recognizes them! He states he encountered them in Fez. His disciples spread throughout Fez, Taza, and beyond, outdoing one another in lauding him and transmitting astounding miracles attributed to him. He was laid to rest outside Bāb al-Futūḥ near Rawḍat al-Anwār, between the tombs of al-Darrās ibn Ismāʿīl and ʿAlī ibn Ṣāliḥ. A dome was erected over his grave for pilgrims, standing intact to this very day.”

The text shaped how generations of Moroccan saints understood spiritual authority. It provided template for recognizing authentic saints: they possessed direct knowledge of unseen realities, demonstrated moral perfection, maintained scrupulous adherence to Islamic law despite their elevated spiritual states, and exhibited humility rather than claiming superiority. These criteria influenced how Moroccans evaluated subsequent claimants to spiritual authority, creating standards against which all would be measured.

Mawlay ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz's teachings emphasized the continuing spiritual presence of the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ and the possibility of direct access to prophetic guidance through vision and unveiling. This emphasis profoundly influenced the development of distinctly Moroccan forms of devotional practice. The proliferation of prophetic prayers (ṣalawāt ʿalā al-nabī), the centrality of dreams and visions in spiritual life, the expectation that saints could encounter the Prophet ﷺ directly—all these became characteristic features of Moroccan Sufism, shaped significantly by the model al-Ibrīz provided.

His insistence on the spiritual significance of sharīfian lineage contributed to the intensification of sharīfian veneration in 12th/18th and 13th/19th century Morocco. While respect for the Prophet's ﷺ descendants had always existed, Mawlay ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz's theological articulation of why sharīfian descent mattered spiritually provided intellectual framework that elevated this veneration from popular sentiment to theological necessity. Moroccan Sufism after al-Ibrīz increasingly emphasized love of Ahl al-Bayt as essential component of spiritual realization, not merely as pious sentiment but as pathway to accessing prophetic baraka.

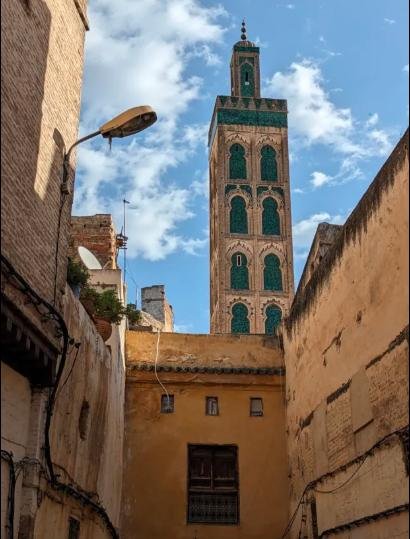

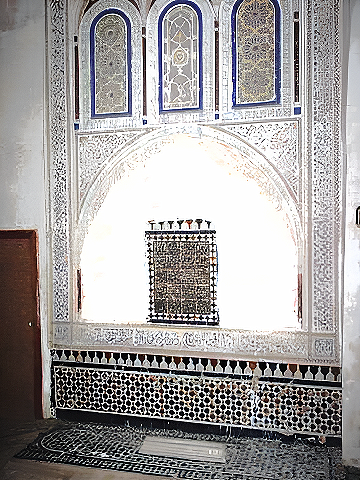

Mawlay ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz's tomb at Bāb al-Futūḥ in Fez became important pilgrimage site immediately following his death. The shrine attracted visitors seeking baraka, intercession, and spiritual guidance from the deceased saint. Pilgrims reported miracles (karāmāt) occurring at the tomb: illnesses cured, problems resolved, spiritual states granted. These reports circulated orally and in writing, reinforcing belief in Mawlay ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz's continuing spiritual efficacy even after death.

The tomb's location at Bāb al-Futūḥ positioned it within the urban fabric of Fez in ways that made it accessible to ordinary believers. Unlike remote rural shrines requiring special pilgrimage journeys, Mawlay ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz's tomb could be visited as part of daily urban life. This accessibility democratized access to his baraka, allowing not just elite scholars but common people to participate in devotional practices centered on his memory.

The shrine became site where multiple forms of authority intersected. Scholars came to pray before undertaking difficult intellectual work. Sufis came seeking spiritual inspiration. Ordinary believers came with practical needs—health, marriage, livelihood. The tomb functioned as multi-purpose sacred site accommodating diverse devotional needs while maintaining its identity as resting place of a saint whose spiritual authority derived from both genealogical distinction and mystical attainment.

Mawlay ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz's influence extended far beyond his immediate disciples and descendants. Al-Ibrīz shaped how Moroccan Islam conceived the relationship between visible and invisible worlds, between this life and the next, between human effort and divine grace. His teachings provided language for articulating experiences that had previously remained private or ineffable, creating shared vocabulary for discussing spiritual realities.

His model of sanctity—sharīfian descent combined with mystical realization, adherence to Islamic law united with visionary experience, humility despite extraordinary spiritual states—became template that subsequent Moroccan saints consciously or unconsciously emulated. Even saints who never read al-Ibrīz operated within religious culture that his teachings had shaped, responding to expectations and criteria his example had established.

The text's continuing relevance into the modern period demonstrates its capacity to speak across historical contexts. While produced in early 12th/18th century Fez, al-Ibrīz continued to be read, studied, and cited into the colonial period and beyond. Modern Moroccan intellectuals engaged with it as artifact of authentic Moroccan Islamic tradition, proof that Morocco had produced sophisticated mystical thought independent of Ottoman or Eastern influences.

For the Dabbagh family, Mawlay ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz's legacy created form of capital that transcended ordinary genealogical distinction. Where many sharīfian families could claim noble descent, the Dabbaghs could claim descent from a saint whose teachings had demonstrably shaped Moroccan religious culture. This gave them authority that mere bloodline alone could not provide—authority grounded in both genealogy and the continuing intellectual and spiritual influence of their most famous ancestor.

5. The Six-Branch Architecture: Geographic and Functional Diversification

By the late 12th/18th and early 13th/19th centuries, the Dabbagh family had evolved from a concentrated lineage in Fez into a distributed network comprising six distinct branches. Each branch occupied specific geographic locations and pursued differentiated economic strategies. This structural diversification represented both organic demographic expansion and deliberate positioning across multiple institutional contexts, creating systemic resilience where disruptions affecting one branch would not compromise the family's aggregate position.

All six branches traced their lineage to a common progenitor, Abū Zayd ʿAbd al-Raḥmān ibn al-Qāsim ibn al-Qāsim ibn Abī al-ʿAbbās Aḥmad, establishing him as the genealogical convergence point in Fez following their return from Andalusia. From this shared node, the Dabbāgh lineage gradually unfolded into a multi-branch configuration that, by the late 12th/18th and early 13th/19th centuries, had assumed a clearly articulated six-branch structure.

This transformation marked a shift from a relatively concentrated familial presence in Fez to a distributed architecture spanning multiple regions and institutional settings. Each branch settled in a distinct geographic zone and cultivated a differentiated economic profile—urban commerce, artisanal production, landholding, religious service, or intermediary roles linking state authority, local society, and markets. Such differentiation was not accidental: it reflected both organic demographic growth and an adaptive logic aimed at embedding the family across diverse social and economic fields.

The Branches

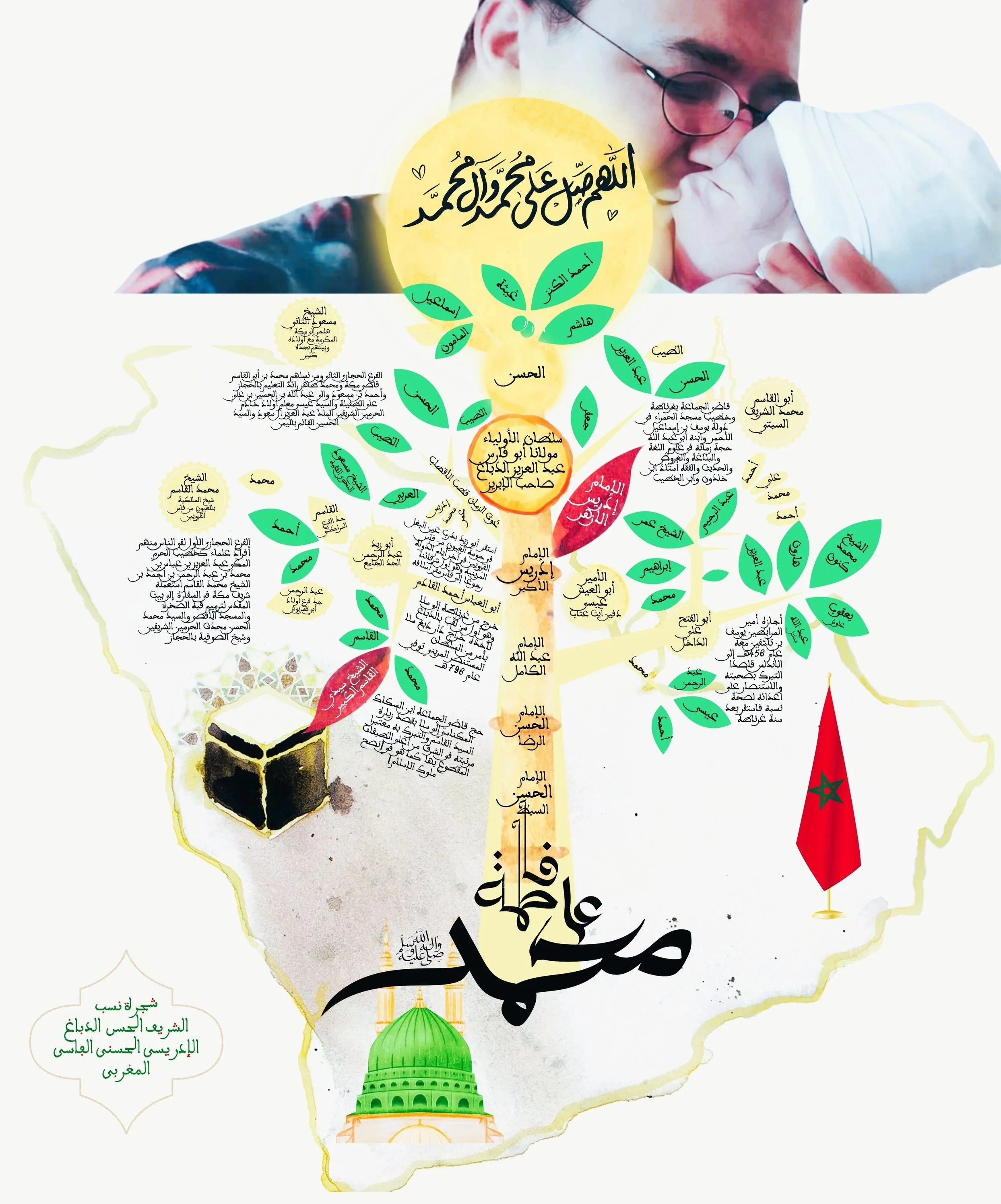

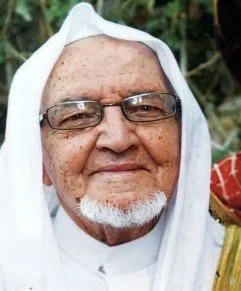

Infographic family tree (mushajjar) of the al-Dabbāgh lineage, visually mapping the six branches of the family and including El Hassane Debbarh, founder of DAR.SIRR, within a symbolic framework that integrates Prophetic descent, spiritual transmission, and Moroccan geographic anchoring.

5.1. Descendants of Mawlay ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz ibn Masʿūd

This branch represents one of the later distinguished lines of the family, emerging through Mawlāy ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz ibn Masʿūd ibn Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad ibn ʿAbd al-Raḥmān. It did not mark the origin of the lineage, which had already been established in Fez for generations, but rather a reorganization of descent into clearly identifiable branches during the late Saʿdian and early ʿAlawī periods.

The immediate ancestors of this branch were already integrated into Fez’s scholarly and religious environment. Aḥmad ibn ʿAbd al-Raḥmān (active 931/ 1524) appears among the sharīfian families of the city during the final Waṭṭāsid decades. His grandson, Aḥmad ibn Muḥammad (active 956 /1549), lived through the Saʿdian conquest of Fez and the reconfiguration of authority that followed. The family maintained its position through scholarly activity and association with established religious circles rather than political office.

The next generation, Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad (active late 10th/16th century), lived during the reign of al-Manṣūr al-Dhahabī (r. 986–1012/1578–1603), when Fez remained a major center of learning. His son, Aḥmad ibn Muḥammad (active 1075/1664), experienced the political fragmentation that followed the decline of Saʿdian power. During this period, family lines began to differentiate more clearly, with some descendants remaining in Fez and others relocating to different regions, including the Ḥijāz.

Masʿūd ibn Aḥmad (d. 1111/1699) consolidated this branch within Fez. Known as a jurist and grammarian, he avoided public office and focused on teaching and writing. His scholarly works, including a commentary on Ibn Mālik’s Alfiyya, reflect the family’s continued engagement with legal and linguistic studies. Through Masʿūd’s sons, especially ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz, this line became clearly distinguishable from other branches of the family.

With Abū Fāris ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz ibn Masʿūd (d. 1131/1719), this branch acquired its most visible figure. ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz, discussed fully in Section 4, produced al-Ibrīz min Kalām Sayyidī ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz al-Dabbāgh through Aḥmad ibn al-Mubārak's compilation. His claim to Khiḍrian initiation, his detailed visions, his theological insistence that prophetic descent affected spiritual capacity—these transformed family identity from scholarly and saintly to something approaching prophetic authority itself. His tomb at Bāb al-Futūḥ became pilgrimage destination, creating permanent infrastructure of sanctity.

“The Dabbaghs abound with saints and righteous men, virtuous scholars living their knowledge, marked by chastity and dignity, humility and devotion. In their midst stands the Axis of the Sphere, the Sun of Exalted Mysteries piercing the unseen of both worlds—Abū Fāris, our master ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz, son of the learned jurist and grammarian our master Masʿūd—through whom their nobility ascends to the very summit.”

Through Idrīs came ʿUmar ibn Muḥammad ibn Idrīs, who occupied the position of preacher (khaṭīb) at Masjid al-Dīwān in Fez and established close relations with Aḥmad al-Tijānī (d. 1230/1815), founder of the Tijāniyya order. ʿUmar's marriage to the daughter of poet Ḥamdūn ibn al-Ḥājj al-Sulamī (d. 1232/1816) embedded him within Fez's literary and scholarly elite.

Through Fāṭima's line came the Sharīf Ḥamīd, grandson of ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz through the matrilineal line. When the young ʿArabī al-Darqāwī (d. 1239/1823) sought spiritual guidance, Ḥamīd directed him toward ʿAlī al-Jamāl (d. 1192/1778), initiating the chain that produced the Darqāwiyya order, one of 19th-century Morocco's most influential Sufi movements.

From ʿUmar ibn Muḥammad descended Muḥammad ibn ʿUmar (d. 1285/1868), described in biographical sources as possessing extraordinary spiritual states, being among the people of kashf, having excellent character and pleasant company, spreading knowledge widely, and gathering many students around him. He cultivated malāmatī spirituality—a spiritual orientation deliberately concealing extraordinary states beneath ordinary appearance and claimed direct contact with al-Khiḍr. His controversial announcement of Shamharūsh al-Jinnī's death divided Fez between supporters and critics.

Muḥammad ibn ʿUmar fathered three sons: Al-Ḥabīb ibn Muḥammad ibn ʿUmar (d. 1326/1908), he represented the consolidation of this lineage, functioning as repository of multiple transmission chains. Sulaymān ibn Muḥammad ibn ʿUmar (d. 1291/1874) - Son of Muḥammad ibn ʿUmar, he maintained the family's spiritual traditions in Fez. ʿAllāl ibn Muḥammad ibn ʿUmar - Another son who carried forward the family's presence in the city.

5.2. The Lineage of Mawlay al-ʿArabī ibn Masʿūd

This branch descended from Mawlay al-ʿArabī ibn Masʿūd, brother of Mawlay ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz. Al-ʿArabī was one of the heirs of his brother's secrets (wārith asrār akhīhi), demonstrating that the charismatic authority of ʿShaykh Abd al-ʿAzīz extended beyond his direct patrilineal descendants to other branches of the family through spiritual transmission. This spiritual inheritance positioned al-ʿArabī's descendants as carriers of the mystical knowledge that had made their uncle famous throughout Morocco.

From al-ʿArabī descended al-Ṭayyib ibn al-Ḥasan ibn al-Ṭayyib ibn al-ʿArabī, who would father six sons and establish what became the most numerous and abundant of all the Dabbagh branches, producing extensive progeny that would spread across both Morocco and the Ḥijāz.

Al-Ṭayyib fathered six sons, each of whom established distinct lineages: Al-ʿArabī ibn al-Ṭayyib produced a well-documented genealogical chain that remained in Fez. ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz ibn al-Ṭayyib (d. 1321/1903), the second son, was described by Ibn Sūda in Itḥāf al-Muṭāliʿ as "religious, worshipful, devout, a master teacher". Known as “Hazz”, he died on the third of Shawwāl and was buried at his home in Burj al-Shurafāʾ in Fez al-Qarawiyyīn. According to Fihrist al-Shuyūkh, Hazz was the one who instructed Muḥammad ibn Jaʿfar al-Kattānī to instruct at the Qarawiyyīn—suggesting significant spiritual authority despite limited biographical information.

“ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz ibn al-Ṭayyib, known as Hazz, was one of the Dabbāgh sharifs known in Fez, a righteous saint (walī ṣāliḥ) renowned for goodness and righteousness.”

Masʿūd ibn al-Ṭayyib (d. 1311/1893), the third son, migrated to the Ḥijāz, creating the geographic split that would define this lineage. His six sons pursued divergent paths, with most establishing the Arabian presence that forms the sixth branch, addressed below.

Al-Ḥasan ibn al-Ṭayyib, the fourth son, established a lineage that remained in Fez. Al-Ḥasan fathered al-Ṭayyib, who fathered Jaʿfar, who fathered al-Ḥasan, who fathered ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz, who fathered al-Ḥasan. This al-Ḥasan produced four children who continued the line in Fez: Aḥmad al-Kanz, Hāchim, Ismāʿīl, and El Mamun.

ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz ibn Aḥmad ibn al-Ṭayyib al-Dabbāgh, known as Hazz (d. 1321/1903), died on the third of Shawwāl and was buried at his home in Burj al-Shurafāʾ in Fez al-Qarawiyyīn. Ibn Sūda described him in al-Itḥāf as "a righteous saint, recognized for goodness and rectitude." According to Fihrist al-Shuyūkh, Hazz was the one who instructed Muḥammad ibn Jaʿfar al-Kattānī (d. 1345/1927) to instruct at the Qarawiyyīn—suggesting significant spiritual authority despite limited biographical information.

The branch exemplifies the family's pattern of maintaining both sedentary and mobile segments. The majority of al-Ṭayyib's sons and their descendants remained in Fez, maintaining properties in the ʿUyūn quarter alongside the first branch and participating in the city's scholarly and administrative networks. This Fez contingent ensured continuity of family presence in Morocco's intellectual capital while preserving access to the Qarawiyyīn's educational resources and the spiritual geography centered on Mawlay ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz's tomb. Simultaneously, Masʿūd's migration to the Ḥijāz created an Arabian presence that allowed the family to maintain connection to both Morocco and the holy cities, creating networks spanning the Islamic world's most significant spiritual centers. The contrast between Muḥammad's choice to remain in Fez and Abū al-Qāsim's residence in the Ḥijāz demonstrates how even within single sibling groups, different members pursued different geographic strategies while maintaining collective family identity.

5.3. The 'Abd al-Rahman/Abū Tarbush Line in Fez

The third branch descends from ʿAbd al-Raḥmān ibn Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad ibn Abī Zayd ʿAbd al-Raḥmān. Its historical significance crystallized in the figure of Muḥammad, known as Abū Ṭarbūsh, ibn ʿAbd al-Ḥafīẓ (d. 1291/1874), whose career offers a revealing case study of how spiritual authority functioned in 13th/19th-century Fez.

The principal sources for Abū Ṭarbūsh’s life are Salwat al-Anfās by Muḥammad ibn Jaʿfar al-Kattānī and Fihris al-Fahāris by ʿAbd al-Ḥayy al-Kattānī. Both authors were direct disciples who studied with Abū Ṭarbūsh and received ḥadīth transmissions from him, lending their testimony particular weight. These works consistently report that Abū Ṭarbūsh openly declared himself quṭb within the scholarly and Sufi circles of Fez—an assertion affirmed by contemporaries rather than shaped retrospectively by later hagiography.

During his formation, Abū Ṭarbūsh acquired several Sufi affiliations. Nevertheless, he attributed his spiritual authority primarily to his ancestor Mawlay Idrīs II, founder of al-ʿĀliyya and central source of Idrisid baraka in Fez. He claimed to consult Mawlay Idrīs on major matters and to receive instruction from him. When disciples sought permission to establish a zāwiya, Abū Ṭarbūsh reportedly replied that Mawlay Idrīs had refused, saying in Darija: Kathrū al-zawāwī wa-qalla man yudāwī (“Zāwiyas have multiplied, yet few are those who truly heal”). As a result, Abū Ṭarbūsh never founded a formal lodge, instead teaching and receiving disciples in various locations throughout Fez.

This claim served clear social and symbolic functions. It positioned Abū Ṭarbūsh above rival shaykhs by asserting unmediated access to Fez’s primordial source of baraka, while simultaneously legitimizing his refusal to institutionalize his following. Whether these consultations were experienced as visionary encounters or functioned as Abū Ṭarbūsh’s own authoritative reasoning attributed to a higher source is ultimately secondary; what matters is their role in structuring authority and insulating him from competition within an increasingly crowded Sufi landscape.

Abū Ṭarbūsh’s outward appearance reinforced this ambiguity. He wore the red Moroccan ṭarbūsh rather than the scholarly turban, a choice that earned him his nickname and visually distinguished him from the formal ʿulamāʾ. Yet he also taught Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī annually during the three sacred months at the zāwiya of ʿAbd al-Qādir al-Fāsī, attracting students from Fez’s most prominent families. His profile thus combined charismatic spiritual claims with recognized scholarly competence, allowing him to appeal simultaneously to mystical and learned constituencies.

Upon his death, Abū Ṭarbūsh was buried in the zāwiya of ʿAbd al-Qādir al-Fāsī, specifically in the corner to the left of the prayer niche—the very place where he had taught. This burial effectively transformed his teaching space into a shrine, ensuring that his bodily presence remained embedded within the locus of his authority.

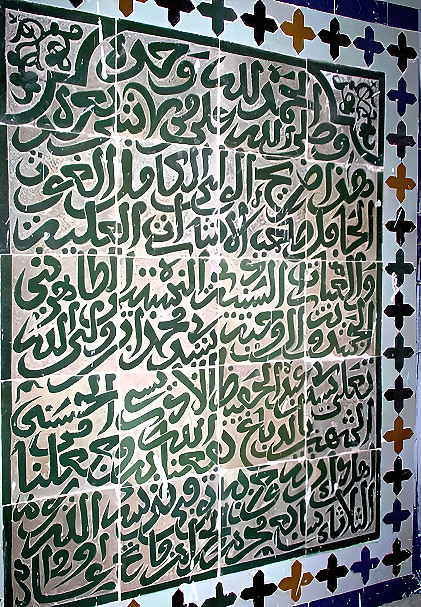

The location carried further significance. Abū Ṭarbūsh was interred alongside ʿAbd al-Qādir al-Fāsī himself and his son Abū Zayd. Beyond his spiritual stature, ʿAbd al-Qādir had served as Shaykh al-Jamāʿa of Fez and was the principal signatory of the 1140 genealogical certificate that authenticated the Dabbagh family’s sharifian descent through eighty scholarly signatures. That document confirmed their lineage from ʿĪsā al-Anwar and their hereditary custodianship of the shrine of Sīdī ʿAlī ibn Ḥirzihim.

“My shaykh and my blessing, the righteous master, the sincere guide, the one who directs to God, who seeks in his spiritual path the presence of God, the exemplary invoker, the knower of God Most High, Abū ʿAbd Allāh Sīdī Muḥammad called Abū Ṭarbūsh—because he would place a ṭarbūsh (fez) on his head and nothing more... He would openly declare his sainthood, inform others of his great elevation and station, relate many of God’s blessings upon him, and mention some of what God had honored him with and bestowed upon him... He would also meet with our Master Mawlay Idrīs al-Azhar, asking him about many matters that arose, and Mawlay Idrīs would answer in ways that satisfied hearts. Among these instances: when a group of his companions asked permission to build a zāwiya where they could gather with him, he delayed them at that time. Then he informed them that he had seen our Master Mawlay Idrīs, may God be pleased with him, and sought his permission for this. Mawlay Idrīs told him: ‘O my son Muḥammad al-Dabbāgh! Do not build yourself a zāwiya. Let the cosmos be your zāwiya—zāwiyas have multiplied while those who truly heal have diminished.’ So he did not build a zāwiya, and continued meeting with them in various mosques, houses, gardens, and places of leisure, nothing more... People would seek him for their important needs, which would be fulfilled through the unseen and spiritual power (himma). Miracles and extraordinary occurrences manifested through him, many became his disciples, and great good appeared through his hands... He would recite the entire Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī annually during the three months at the zāwiya of Sīdī ʿAbd al-Qādir al-Fāsī, in the corner to the right of the prayer niche... I received from him the ḥadīth musalsla with the Prophetic handshake and interlocking of fingers; he shook my hand and interlocked fingers with me at the Idrīsid shrine... He would most often seek refuge in the Qarawiyyīn Mosque near the retreat cell, and at the shrine of our Master Mawlay Idrīs by the chair facing the courtyard pavilion, to the left of one facing the dome. A trustworthy person informed me that he vowed to visit our master Idrīs, may God be pleased with him, for forty days, asking God to let him meet the Pole of the Age. He said: ‘After completing the forty days, I happened to open a shop for buying and selling, having previously been a student of knowledge. As soon as I entered it, Sīdī Muḥammad al-Dabbāgh came to me, entered with me, sat down, and said: “People come to the Pole, and among them are those upon whom the Truth Most High bestows favor, so the Pole comes to them!”‘ He said: ‘I did not grasp the meaning of his words—that he was indicating to me that he was the Pole and that he had come to me—until some time later!’ Then this informant mentioned another story to me: Sīdī Muḥammad al-Dabbāgh came to someone, and that person said to him: ‘O master, I ask you by God to tell me where the Pole is at this time?’ and words to this effect. He replied: ‘Ḥawzī’ (in my possession). The man thought he was telling him the Pole was from the Ḥawz region, but he was actually indicating that the Pole’s station was in his possession and dominion, that he himself held it.””

Securing burial for Abū Ṭarbūsh beside the scholar who had validated the family’s genealogy established a lasting spatial convergence between documentary legitimacy and charismatic authority. Visitors to the zāwiya encountered both forms of validation side by side: the grave of the administrator-scholar who certified bloodlines and the grave of the mystic who claimed direct instruction from Mawlay Idrīs II.

Finally, the vision at Wādī al-Shurafāʾ, in which Abū Ṭarbūsh reported that the Prophet ﷺ declared the Dabbaghs and the Kattānīs the finest of his progeny, became a narrative resource mobilized by both families in later generations. In particular, the connection with the al-Kattānī family proved decisive. As the Kattānīs rose to prominence within Fez’s scholarly elite, many attributed their ascent to the baraka transmitted through their discipleship with Abū Ṭarbūsh, embedding his legacy within the long-term reconfiguration of Morocco’s sharifian and scholarly hierarchies.

Later members of this branch sustained the family's religious authority. Ibrāhīm ibn Abī Ṭarbūsh (d. 1329/1911), emerges from sources as a figure of considerable scholarly standing. ʿAbd al-Ḥafīẓ ibn al-Ṭāhir al-Fāsī al-Fihrī devoted extended treatment to him in Riyāḍ al-Janna, describing him as "among the highest of his time in rank, and most noble in distinction, a great scholar, ḥadīth specialist, Sufi."

Ibrāhīm conducted annual recitations of Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī during Rajab and Shaʿbān for approximately forty years at the Fāsī zāwiya, completing the text in about forty sessions before assemblies of scholars and notables. ʿAbd al-Ḥafīẓ's father regularly attended these sessions. The account emphasizes Ibrāhīm's pleasant company, copious benefits, illuminated countenance, constant remembrance and worship, quick tears, humble heart, elevated spiritual aspiration, and abstinence. He was described as "venerated by elite and common people alike, greatly humble, gentle, loving toward people of goodness."

Ibrāhīm studied with multiple Fez scholars, particularly depending on Abū al-ʿAbbās al-Warghiyālī. From his father Muḥammad he received extensive training, hearing ḥadīth works from him repeatedly—Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī more than twenty times alone. During pilgrimage to Mecca, he received authorizations from Aḥmad Daḥlān, Abū al-Maḥāsin al-Qāwuqjī al-Ṭarāblusī (who transmitted from al-Sanūsī, al-Marghīnī, al-Baʿalawī, al-ʿAydarūs al-Saqqāf, al-ʿAṭṭās, and ʿAbd al-Qādir al-Kūhān), Ḥasan al-ʿAdawī (from whom he received the Shādhiliyya order), Aḥmad ibn Manṣūr al-Rifāʿī (from whom he received the Rifāʿiyya), and Aḥmad al-Dahhān in Mecca (from whom he received the Idrīsī divine names with their sciences, properties, and permissions for their use). His funeral attracted large crowds, and people greatly mourned his loss.

Muḥammad ibn Idrīs ibn ʿAbd al-Hādī ibn ʿAbd al-Raḥmān (d. 1350/1931) was described as a man of letters, poet, and well-read scholar from Fez. He was among the perfect knowers and righteous attainers, abundant in litanies and remembrances, performing night vigils, abstemious toward the world, devoted to his Lord, indifferent to worldly matters, finding intimacy with his Master in secret and private conversation, knowing the secrets of God's majesty, silent and dignified, speaking only when necessary, constantly contemplative, pure of heart, illuminated within, constantly engaged in righteous deeds, devoted to Quranic recitation, immersed in love of his grandfather the Messenger of God. He authored a significant work containing numerous prayers upon the Prophet ﷺ titled Miftāḥ al-Asrār fī-mā Yataʿallaq bi-l-Ṣalāt ʿalā Sayyid al-Abrār (The Key of Secrets Concerning Prayer upon the Master of the Righteous). The work survives in the National Library, comprising 189 pages. Ibn Sūda included his biography in Itḥāf al-Muṭāliʿ.

Muḥammad ibn al-Hādī ibn Muḥammad ibn ʿAbd al-Hādī ibn ʿAbd al-Raḥmān (d. 1284/1867) served as muqaddam of the Kuntiyya in Fez. The Kuntiyya represented one of several Qādiriyya branches active in Morocco, distinguished by its Saharan origins and extensive networks reaching into West Africa. His role provided institutional platform connecting the family to devotional networks extending beyond Fez.

Four brothers from an earlier generation—Aḥmad ibn ʿAbd al-Raḥmān, Idrīs ibn ʿAbd al-Raḥmān, Mḥammad ibn ʿAbd al-Raḥmān, and ʿAbd al-Mālik ibn ʿAbd al-Raḥmān—signed the bayʿa document for Sultan Mawlāy al-Yazīd ibn Muḥammad ibn ʿAbd Allāh (r. 1204–1206/1792–1795). Their inclusion demonstrates the branch's integration into Fez's class of notables whose endorsement was sought for dynastic transitions. That four brothers signed together indicates the family's collective political positioning.

A subsidiary line maintained presence in Fez through Muḥammad ibn ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz ibn Muḥammad (d. 1428/2008), who served as conservator of the Qarawiyyīn Library for over twenty-three years while authoring works on literature and history.

The branch remained concentrated in Fez's ʿUyūn quarter, maintaining the residential pattern that facilitated sharīfian networks and collective assertion of privileges.

5.4. The Marrakesh Lineage

The fourth branch descended from Idrīs ibn al-Qāsim ibn Abī Zayd ʿAbd al-Raḥmān, establishing itself in Marrakesh. The city functioned as Morocco's southern capital with distinct opportunities from Fez's saturated sharīfian landscape. Marrakesh possessed its own religious establishment, commercial networks, and patronage structures, allowing family members to build reputations independent of northern comparisons.

Muḥammad al-Dabbāgh (d. 1210/1795) served as judge of Agadir, demonstrating the branch's success in securing judicial appointments in southern Morocco's urban centers. The position required legal expertise and political networks extending beyond Marrakesh into the Sūs region.

Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad ibn al-Ḥasan, known as al-Faqīh ibn al-Ḥasan (d. 1371/1952), achieved appointment as shaykh al-jamāʿa of Marrakesh, the city's highest religious office. This occurred during the late colonial or early independence period, demonstrating sustained religious authority through political transformations. The position involved supervising mosques, madrasas, and endowments, requiring both scholarly credentials and administrative capacity. That he held this office into 1371/1952 suggests he navigated the transition from French protectorate to Moroccan independence while maintaining institutional position.

The branch's most dramatic adaptation appeared in Idrīs ibn al-Ṭayyib ibn Ibrāhīm al-Dabbāgh's career trajectory. He served as Morocco's ambassador to Italy (1959-1961) during the early independence period, then as Minister of Commerce, Industry, Mines, and Maritime Navigation (1963), and subsequently as vice-president of Banque Commerciale du Maroc. This progression from diplomacy through ministerial office to banking leadership demonstrates how sharīfian credentials could be translated into political and economic capital in postcolonial Morocco. The ʿAlawī monarchy's policy of promoting sharīfs into state positions created opportunities for families like the Dabbaghs to transition from traditional religious vocations into modern professional and political roles while maintaining their genealogical identity.

Descendants of ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz ibn al-Walīd ibn Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad ibn ʿAlī ibn ʿAbd al-Raḥmān ibn Aḥmad ibn Idrīs remained permanently established in Marrakesh into the contemporary period.

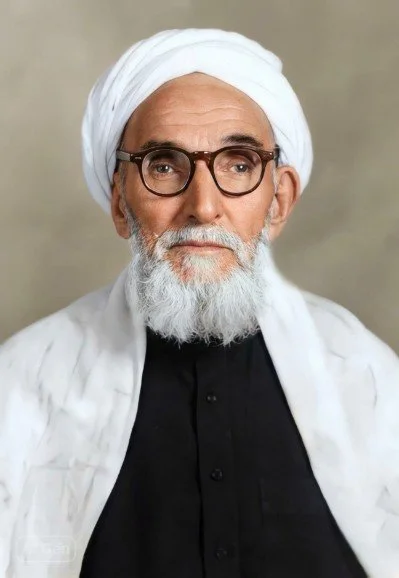

5.5. The ḥaramayn Mālikī Imams

Geographic expansion eastward produced the family's most distinguished institutional achievement: monopolization of the Mālikī imam position at Mecca's Sacred Mosque across multiple generations. This branch descended from Muḥammad al-Qāsim, known as shaykh al-Mālikiyya, ibn Muḥammad al-Ṣaghīr ibn Aḥmad ibn Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad ibn ʿAbd al-Raḥmān, who had entered Fez from Salé. In Meccan context, the family became known as al-Mālikis, their identity defined by institutional function rather than genealogical distinction alone.

The Mālikī imamate passed through successive generations, creating hereditary association between the Dabbagh name and this prestigious position. The complete genealogical chain demonstrates the family's careful documentation of their line:

ʿAbbās ibn ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz ibn Muḥammad ibn ʿAbd al-Raḥmān ibn Aḥmad ibn Muḥammad al-Qāsim (d. 1353/1935) held the Mālikī imam position while simultaneously serving in diplomatic capacities for Sharīf Ḥusayn ibn ʿAlī, the Hashemite ruler of the Ḥijāz. His diplomatic assignments took him to Jerusalem to supervise restoration of the Dome of the Rock and al-Aqṣā Mosque, and to Abyssinia to oversee mosque construction. These missions combined religious authority with political service, demonstrating how the family's Mālikī legal expertise and sharīfian status translated into trusted roles under Hashemite authority.

ʿAbbās ibn ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz ibn Muḥammad (1335-1391) succeeded his father in the imam position, maintaining the family's hold on this office through the dramatic political transition from Hashemite to Saudi rule over the Ḥijāz in 1924-1925. His ability to retain the position despite regime change suggests the family had established sufficiently deep roots in Meccan society that their institutional role transcended particular political authorities.

Muḥammad al-Ḥasan ibn ʿAlawī ibn ʿAbbās ibn ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz (d. 1425/2004) achieved particular prominence, earning the titles muḥaddith al-ḥaramayn al-sharīfayn and shaykh al-ṣūfiyya bi-l-Ḥijāz. When he died, funeral prayers were held in the Sacred Mosque, and he was buried in al-Muʿallāh cemetery in a majestic funeral. Crown Prince ʿAbd Allāh ibn ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz Āl Saʿūd (later King ʿAbd Allāh) attended the burial ceremonies on behalf of his brother King Fahd, indicating the family's continuing recognition at the highest levels of Saudi authority despite their Mālikī rather than Ḥanbalī affiliation and their historical associations with the displaced Hashemite rulers.

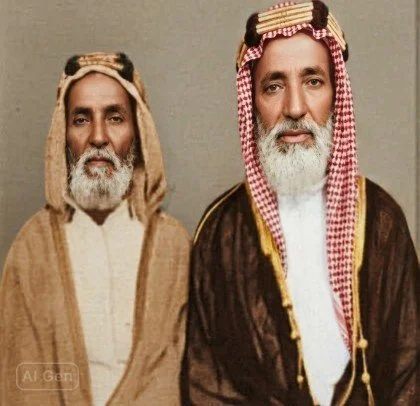

5.6. The Medinese Restoration

During Sultan Mawlay al-Ḥasan I's reign (1290-1311/1873-1894), Masʿūd ibn al-Ṭayyib ibn al-Ḥasan ibn al-Ṭayyib ibn al-ʿArabī ibn Masʿūd ibn Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad ibn ʿAbd al-Raḥmān (d. 1311/1893) undertook pilgrimage to the Ḥijāz. The holy cities under Hashemite rule proved particularly welcoming to sharifs, and Masʿūd found the environment conducive enough to relocate his family. Sources describe him as a walī ṣāliḥ. He died and was buried in Mecca.

Masʿūd fathered six sons. Two returned to Morocco while four remained in Arabia, their descendants navigating the 1924-1925 transition from Hashemite to Saudi rule.

Muḥammad ibn Masʿūd (d. 1340/1922) remained in Fez, becoming a Tijānī muqaddam under al-ʿArabī al-ʿAlamī of Zarhūn (d. 1320/1902). His teachers included Muḥammad ibn al-Madanī Kannūn, Aḥmad ibn Bannānī, and ʿAbd al-Mālik al-ʿAlawī al-Ḍarīr. ʿAbd al-Ḥafīẓ al-Fāsī al-Fihrī described him as al-faqīh al-ṣūfī, al-khayr al-dhākir, al-mutaʿabbid al-ṣāliḥ al-waqūr, baqiyyat al-salaf. He composed versified Sufi works, including a poem on Sufi orders that Aḥmad ibn Muḥammad al-Khaḍīr al-ʿImrānī commented upon in Saʿd al-Shumūs fī Makārim al-Akhlāq wa-Qamʿ al-Nufūs. He was buried at Bāb al-Futūḥ.

Abū al-Qāsim ibn Masʿūd (d. 1351/1931) established a household in the Ḥijāz before returning to Morocco to marry his cousin Lalla Ghīta, daughter of Jaʿfar ibn al-Ṭayyib. He settled in Marrakesh. ʿAbd al-Ḥayy al-Kattānī mentioned him in Fihris al-Fahāris, noting his correspondence with scholars in Mecca.

Aḥmad ibn Masʿūd (d. 1394/1974) was born in Medina, memorized the Quran, and was appointed judge of al-ʿAqaba under Sharīf Ḥusayn ibn ʿAlī. After the Saudi conquest, he relocated to Transjordan, connecting with Amīr ʿAbd Allāh. He was appointed to education in Ṭufīla, then in 1383/1946 became chief judge there. He donated his library to the University of Jordan and maintained friendship with Prince al-Ḥasan ibn Ṭalāl. He died in Riyadh. Jordan's Ministry of Education named a school in Ṭufīla after him.

Muḥammad Ṭāhir ibn Masʿūd (d. 1378/1966) became pioneer of education in the Ḥijāz. King ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz appointed him Minister of Education. He established schools across regions and founded a school for preparing foreign scholarship students. Before unification, he served as Secretary-General of the Ḥijāzī National Party.

Al-Ḥusayn ibn ʿAbd Allāh ibn Masʿūd (d. 1381/1962) fled Mecca to Ḥaḍramawt when Saudi forces arrived. He founded Falāḥ schools across Ḥaḍramawt, al-Mukallā, ʿAdan, and Yāfiʿ. He adopted the title al-Dāʿī ilā Allāh and built military force. British authorities arrested him in 1380/1961 and delivered him to Saudi custody. He died in Jīzān prison the following year.

ʿĪsā ibn ʿAbd Allāh ibn Masʿūd (d. 1434/2013) joined teaching at age 16. He taught at Madrasat al-Anjāl in Riyadh, educating King ʿAbd Allāh, King Fahd, Prince Mutʿib, and Prince Ṭalāl. Crown Prince ʿAbd Allāh attended his burial in Ṭāʾif's cemetery of ʿAbd Allāh ibn al-ʿAbbās.

The branch's geographic distribution across Morocco, Jordan, and the Arabian Peninsula, combined with members' diverse responses to political upheaval—accommodation, resistance, or specialized service—demonstrates adaptive strategies ensuring family survival across multiple regimes.

6. Conclusion: Survival, Scholarship, Sanctity

The Dabbagh family's fourteen-century trajectory from the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ through the Idrīsid founding of Morocco to the present demonstrates how sharīfian families maintained position through embodying sanctity, scholarship, and social authority that political powers required for legitimacy. This was not royal power but something more durable: religious authority rooted in prophetic genealogy, scholarly transmission, and recognized baraka.

Morocco remained fundamentally Idrīsid regardless of which dynasty held political power. Fez was founded by Idrīs I, its sacred geography organized around Idrīsid tombs and sanctuaries. Subsequent rulers—Marinids, Saʿdians, ʿAlawīs—governed Morocco politically, but the religious and cultural foundations remained Idrīsid. Sharīfian families like the Dabbaghs maintained authority derived from that founding reality.

Three elements sustained this position. First, sanctity created recognition that politics alone could not provide. Mawlay ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz's tomb at Bāb al-Futūḥ became pilgrimage site through popular recognition of his spiritual station. Abū Ṭarbūsh's burial alongside ʿAbd al-Qādir al-Fāsī linked the family to the scholar who had authenticated their genealogy with eighty signatures. The vision at Wādī al-Shurafāʾ, whatever its historical status, functioned as narrative validating the family's position. These forms of authority existed alongside but independent of political power.

Second, scholarship provided indispensable services across changing regimes. The family's consistent production of judges, muftis, ḥadīth specialists, and teachers meant they controlled knowledge political authorities needed. The 1140/1727 certificate demonstrated embeddedness in scholarly networks. Muḥammad al-Ḥasan ibn ʿAlawī's over one hundred works on Islamic sciences in 20th-century Mecca continued this tradition. Regimes required such scholars to staff institutions and legitimate decisions.

Third, prophetic descent commanded recognition across political boundaries. When Aḥmad ibn Masʿūd relocated from Hashemite Ḥijāz to Jordanian Ṭufīla, his sharīfian status secured position. When Muḥammad Ṭāhir served Saudi Arabia despite previous Hashemite associations, his credentials transcended political divisions. When ʿĪsā taught Saudi princes, his authority derived partly from genealogy. Sharīfian families belonged to networks spanning the Islamic world, recognized wherever they settled.

The family's geographic distribution across Fez, Marrakesh, Mecca, Medina, Jeddah, and Riyadh reflected these networks rather than mere migration. Sharīfs moved between cities maintaining scholarly contacts, accessing pilgrimage opportunities, and positioning family members across multiple centers. Abū al-Qāsim's correspondence from Marrakesh with Meccan scholars, documented in Fihris al-Fahāris, exemplified these connections.

Economic resources sustained this positioning. The 790/1388 Marinid grant of revenue from the Dār al-Dabbāgh in Sala, later reinforced by Alawid endowment of one hundred fertile hectares at Sīdī Harāzem, provided foundation. The family built substantial homes in Fez's ʿUyūn quarter, maintained endowments, held teaching positions, and received support through Sufi networks. Aḥmad ibn Masʿūd's library donation to the University of Jordan indicated resources beyond subsistence. Economic stability allowed focus on scholarship and spiritual practice rather than constant struggle for survival.

The family's fourteen-century persistence demonstrates that sharīfian status, when combined with genuine scholarship and recognized sanctity, created position that new political authorities found necessary to acknowledge. They did not rule, but they occupied space rulers could not ignore. They did not command armies, but they commanded respect based on genealogy, knowledge, and baraka. They served successive regimes while maintaining identity rooted in Idrīsid heritage and prophetic descent.

As long as Morocco remembers its Idrīsid founding, as long as Muslims value chains of transmission connecting them to the Prophet ﷺ, as long as people recognize sanctity in particular lineages, sharīfian families like the Dabbaghs will maintain position. They endure not through political power but through embodying forms of authority—genealogical, scholarly, spiritual—that Islamic societies continue to recognize as legitimate. The infrastructure they built across fourteen centuries—tombs, books, networks, documented genealogies—functions still, connecting contemporary generations to foundational moments of Moroccan Islamic history.