The Almohad Empire: Mahdism, Power, and the Making of the Makhzan

The emergence of Muhammad ibn Tumart and the Almohad movement (al-Muwaḥḥidūn) has often been approached through fragmented lenses: doctrinal radicalism, Berber tribal mobilization, or charismatic reform. Such readings, while partially valid, tend to isolate the phenomenon from the deeper transformation of authority taking place in the western Islamic world during the late 5th/11th and early 6th/12th centuries. This article adopts a different perspective. It situates Ibn Tūmart's Mahdist daʿwa within a moment of reconfiguration (taḥawwul) in Islamic legitimacy, when inherited forms of sovereignty were no longer sufficient to command unquestioned obedience.

By this period, the architecture of universal authority had entered a phase of ikhtilāl. The Abbasid caliphate persisted largely as a symbolic reference; the Fatimid project had lost much of its doctrinal vitality; and the Umayyad experience in al-Andalus had dissolved into fragmented polities. What followed was not a civilizational decline, but an exposure (inkishāf) of the limits of caliphal universality. Across the Islamic world, regional powers began to experiment with alternative foundations of legitimacy. Morocco, far from being marginal, became one of the most consequential arenas in which these experiments were tested.

Before the Muwaḥḥidūn, the Almoravid order (a-Murābiṭūn) represented a condition of equilibrium rather than crisis. Built upon Ṣanhāja leadership, Mālikī jurisprudence, and ribāṭ discipline, it governed effectively so long as authority remained socially and doctrinally uncontested. Its weakness did not lie in administrative incapacity, but in the absence of a discursive language capable of responding to challenges that were no longer merely juridical. When legitimacy itself became the object of interrogation, Mālikī fiqh (jurisprudence) alone proved insufficient.

It was within this shifting landscape that Ibn Tūmart emerged—not initially as a Mahdī, but as a teacher, judge, and moral authority shaped by Niẓāmiyya-oriented kalām (speculative theology) and endowed with Idrīsid lineage as latent symbolic capital. His Mahdism must therefore be understood less as a theological eccentricity than as a technology of acceleration, capable of mobilizing obedience rapidly by collapsing doctrine, morality, and sovereignty into a single claim.

Yet the Muwaḥḥidūn project cannot be reduced to Mahdism alone. Alongside revolutionary daʿwa, the Muwaḥḥidūn introduced something equally decisive into Moroccan political history: the makhzan. For the first time, authority was not only asserted doctrinally but organized, displayed, and ritualized—through centralized administration, court hierarchy, official dress, regulated ceremony, refined cuisine, and a visible grammar of power. If the Idrīsids had endowed Morocco with baraka as a source of sacred continuity, the Muwaḥḥidūn endowed it with makhzan as an apparatus of governance and statecraft.

This article argues that the tension between these two forces—Mahdist acceleration and makhzan consolidation—defined both the success and the fragility of the Almohad state. Mahdism proved powerful at inception but difficult to sustain; makhzan proved indispensable but unstable when severed from inherited sanctity. By tracing the Almohad trajectory from ascent to infirāṭ al-sharʿiyya (unravelling of legitimacy), and by contrasting it with the later Marinid reconciliation of makhzan and Idrīsid baraka, this study seeks to illuminate a recurring Moroccan pattern: authority endures not through perpetual correction, but through the careful anchoring of power in memory, lineage, and continuity.

1. The Almoravid Order at Equilibrium

Before the emergence of Ibn Tūmart's challenge, the political order established by the Murābiṭūn represented a moment of equilibrium grounded in an achievement without precedent in Moroccan history. For the first time, a single power succeeded in unifying the Moroccan tribal field under Ṣanhāja leadership while simultaneously binding the two ʿudwas—the ʿudwa of al-Maghrib al-Aqṣā and the ʿudwa of al-Andalus—into one integrated sphere of command. This unification was not symbolic. It entailed direct Moroccan governance over al-Andalus and the consolidation of a vast Ṣanhāja territorial continuum extending southward across the Sahara toward the Niger and Senegal corridors. The authority of the Murābiṭūn was therefore first and foremost territorial, integrative, and geopolitical.

This unprecedented spatial command constituted the backbone of the Murābiṭūn power. Yet territorial unification alone does not explain the regime's stability or its immediate intelligibility to the elites of al-Andalus and the wider western Islamic world. That role was fulfilled by Mālikī jurisprudence, which functioned not merely as law, but as a code of legitimacy. Mālikism carried the symbolic weight of being the madhhab of the imām of Dār al-Hijra and had been adopted by the Umayyads of al-Andalus since the early 3rd/9th century as the marker of Sunnī orthodoxy. By ruling through Mālikism, the Murābiṭūn did not invent legitimacy; they activated an already imperial language of authority, immediately recognizable to Andalusi jurists and scholars as orthodox, Sunnī, and politically lawful.

In the Moroccan context, however, neither Ṣanhāja force nor Mālikī orthodoxy could operate in abstraction. The decisive mediating element was Idrīsid baraka, transmitted and operationalized through the ribāṭ system. Ribāṭs such as Aglū, founded and controlled by Idrīsid lineages, functioned as sites where Mālikī doctrine acquired local authorization and where Ṣanhāja mobilization gained moral recognition. The term isargkinen—used by Masmūda speakers to designate sharīfian lineages—reveals how deeply Idrīsid sanctity was embedded in Moroccan linguistic and social practice. Mālikism did not enter Morocco as an external imposition; it was actively transmitted and legitimized through Idrīsid networks, most notably through Waggāg ibn Zallū (d. 445/1054), the Idrīsid sharīf who anchored Abu Imran al-Fasi's (d. 430/1039) Mālikī network in sharīfian authority. Juridical orthodoxy thus acquired local sanctity by passing through Idrīsid hands, embedding itself within a sacred geography already recognized across Moroccan society. In this sense, Idrīsid baraka did not compete with the Murābiṭūn authority; it enabled it.

The stability of the Murābiṭūn order thus rested on a triple convergence: Ṣanhāja unification produced sovereignty, Mālikism supplied an imperial legitimacy-language, and Idrīsid baraka grounded that legitimacy locally. Within this configuration, Mālikī fiqh fulfilled its proper function as an instrument of administration and normativity. It regulated markets, contracts, worship, and adjudication across a newly unified space. It did not need to theorize sovereignty because sovereignty appeared self-evident, secured by territorial command and reinforced by inherited sanctity.

The geographic placement of Marrakesh, the Murābiṭūn capital founded circa 463/1070, reveals both the logic and the latent vulnerability of this equilibrium. Built at the northern edge of the High Atlas mountains, Marrakesh secured control over trans-Saharan trade routes and military corridors linking the Maghrib to al-Andalus. Yet this logistical advantage came with a structural risk: the capital was embedded in Masmūda territory, the mountain-based Berber confederation whose social depth and defensive mobility contrasted sharply with the desert-based Ṣanhāja origins of the ruling elite. The alternative—building the capital on the Atlantic coast within Ṣanhāja-affiliated zones—was foreclosed by the Murābiṭūn suppression of the Barghawāṭa, whose heterodox Islam and subsequent massacre left the region militarily pacified but politically unreliable. Marrakesh was thus chosen not because it was tribally secure, but because all other options were more dangerous. The capital functioned effectively so long as Masmūda networks remained politically inactive, yet its very existence placed Ṣanhāja sovereignty within the gravitational field of a potential rival confederation.

The ribāṭ system further stabilized this order. Under Murābiṭūn rule, ribāṭs were not alternative centers of authority but nodal points of cohesion, linking ascetic discipline, military readiness, and tribal allegiance. Their role was preservative rather than oppositional, reinforcing obedience rather than contesting command. The field of legitimacy remained singular; no competing moral horizon had yet emerged that required justification beyond precedent and force.

This equilibrium rested on one unstated condition: that legitimacy itself would never become an object of interrogation. So long as authority remained self-evident—secured by conquest, sanctified by baraka, and regulated by fiqh—the system required no further justification. Mālikī silence on speculative theology functioned as a safeguard, preserving unity by avoiding unnecessary articulation of creed. But this silence was conditional. It worked only so long as belief remained implicit and obedience uncontested. Once belief itself became the object of scrutiny, the equilibrium could no longer absorb the pressure without transformation.

What followed was not the failure of unification, but the testing of its foundations. The Murābiṭūn governed effectively until the question of power shifted from who rules to by what right. It is within this transformed horizon, and against the backdrop of a fully unified Moroccan–Andalusi order, that Ibn Tūmart's intervention must be understood.

2. Ibn Tūmart Before the Mahdī Claim

Before any Mahdist claim was articulated, Muhammad ibn Tumart entered the Moroccan field as a figure of authority already formed. His position emerged from an accumulated capital combining learning, discipline, lineage, and timing. Born circa 469-473 AH (1076-1080 CE) in the Masmūda village of Igīlīz in the Sūs region, he bore the name Muhammad ibn 'Abd Allah—conforming to the widespread expectation that the Mahdi should replicate the Prophet's ﷺ own name and patronymic. The name "Tumart" came from his mother, who upon his birth exclaimed in Masmūda Amazigh, "Atumert!" (my joy), making "Tumart" his permanent designation. As an Idrīsid sharīf descended from Imām Idrīs I, he occupied a position within Moroccan society where sharīfian lineage carried inherent moral authority and the expectation of corrective intervention, even in the absence of direct political power.

His intellectual formation unfolded in Baghdad between approximately 500 and 511 (1106-1117), where he encountered the Niẓāmiyya institutional system and the synthesis articulated by Abū Ḥāmid al-Ghazālī (d. 505/1111). The Niẓāmiyya project, established under Seljuq patronage, represented a composite Sunnī order that refused to separate law, theology, and spirituality. It combined Shāfiʿī fiqh, Ashʿarī kalām, and a regulated form of taṣawwuf into a single grammar of authority designed to stabilize belief and obedience against both Shiʿi imamate doctrines and unregulated philosophical speculation.

Ibn Tūmart's encounter with al-Ghazālī (d. 505/1111) and exposure to the teachings of al-Ghazālī's master, al-Juwaynī (d. 478/1085), proved formative. He absorbed from their creedal works—particularly al-Juwaynī's systematic theology and al-Ghazālī's doctrinal texts—a synthesis of kalām, fiqh, and taṣawwuf as an integrated apparatus of authority. More decisively, he internalized a principle that would become central to his later challenge: that al-naẓar ʿaqlī (rational inquiry) constitutes a religious obligation within faith, not outside it. The suspension of reason, in this framework, was not piety but a gateway to doctrinal deviation. This transformed taqlīd—the reliance on inherited precedent—from a virtue of restraint into a potential site of error when it became the suspension of critical examination.

Ibn Tūmart's mastery of taʾwīl—the disciplined interpretation of ambiguous scriptural passages—equipped him with a technology of authority that Mālikī jurisprudence in the Maghrib had historically avoided. Where Mālikism preserved unity through silence on speculative theology, Ashʿarī kalām provided tools for adjudicating belief when challenged. What Ibn Tūmart carried back to Morocco was therefore not merely doctrine, but an institutional grammar of Sunnī power: a fully formed system for defining orthodoxy, identifying error, and enforcing alignment through intellectual rather than merely juridical means. This comprehensive mastery—spanning uṣūl al-dīn, uṣūl al-fiqh, kalām, and the systematic refutation of doctrinal deviation—led Ibn Khaldun to assess him as baḥrun lā sāḥila lahu (a sea without shore), a figure whose learning proved so vast and penetrating that its limits could not be discerned.

Ibn Tūmart's return to the Maghrib was not a retreat but a calculated redeployment of accumulated authority. His journey westward reveals a consistent pattern: the testing of existing power through moral enforcement before doctrinal challenge. In Alexandria, he disputed with the prominent Mālikī jurist Abū Bakr al-Ṭurṭūshī (d. 525/1130) over the meaning of the Quranic imperative al-amr bi'l-maʿrūf wa-l-nahy ʿan al-munkar (to command right and forbid wrong). The disagreement was not merely academic; it concerned whether this principle authorized direct intervention against authority or remained confined to exhortation and personal conduct.

During his sea passage from Egypt to Ifrīqiya, sources report that Ibn Tūmart so persistently admonished the ship's crew that they keelhauled him, dragging him behind the vessel. That he survived this ordeal—whether through resilience or hagiographic embellishment—reinforced his reputation for uncompromising moral severity. At the port of Mahdiya, then center of the Zirid emirate under Yaḥyā ibn Tamīm (d. 515/1121), he established himself on the steps of the local mosque, teaching uṣūl al-dīn and uṣūl al-fiqh to all comers. His fluency and pedagogical authority drew large crowds, prompting the Zirid emir to convene a council of Mālikī scholars to examine his teachings. Once convinced he harbored no political ambitions in their emirate, these jurists were sufficiently impressed that the emir himself requested Ibn Tūmart's blessing.

At Bijāya, then a major center of Ḥammādid enclave, Ibn Tūmart's method escalated from teaching to physical enforcement. During an Eid al-Fiṭr celebration, he beat with his staff both men and women whom he found mixing together in the public prayer area, provoking popular outrage and official intervention. After being requested to leave the city, he gathered sympathizers who ransacked the commercial quarter, smashing wine jars and destroying shops where alcohol was sold, all while chanting Quranic verses. This was ḥisba—the enforcement of communal moral standards—enacted not through legal procedure but through direct action.

It was at the nearby village of Mallala that Ibn Tūmart encountered the figure who would become his successor: ʿAbd al-Muʾmin ibn ʿAlī (d. 558/1163). The hagiographic account of their meeting, recorded by Ibn Tūmart's companion Abū Bakr al-Baydhaq, presents the encounter as providentially determined. Whether or not the details are historically precise, the narrative reveals how authority was understood to operate: Ibn Tūmart identified ʿAbd al-Muʾmin not through consultation or selection, but through recognition of divine signs.

“Know that when ʿAbd al-Muʾmin went to the Imām, he met [Ibn Tūmart’s] students on the road and accompanied them to the door of the mosque. The Infallible One (al-Ma’sūm) raised his head and bade him stand before him, saying, ‘Come in, young man.’ But ʿAbd al-Muʾmin wanted to sit among the others, so the Imām, the Infallible Guided One, said, ‘Come near, young man.’ As he was coming nearer the Infallible Imām came up to him until he was beside him and said to him, ‘What is your name, oh youth?’ ʿAbd al-Muʾmin,’ he replied. Then the Infallible One said, ‘And your father is Ali?’ ‘,Yes,’ he replied. The others were amazed at this. Then [Ibn Tumart] said, ‘Where are you from?’ ‘From near Tlemcen,’ he replied, ‘From the plain of Gumlya’. Then the Infallible One said, ‘From Tajra, no?’ ‘Yes,’ he replied. The others were even more amazed. Then the Infallible One said, ‘Where do you wish to go, oh youth?’ “He answered, ‘Sidi, to the East to acquire knowledge there’. The Pure One said, ‘You have found in the West that knowledge you wish to partake of in the East’. When it was time for the students to depart from the lecture, the Khalifa wanted to depart as well, but the Infallible One said, ‘Stay with us, young man,’ and he answered, ‘Yes, oh faqih. So he stayed with us, and when night fell, the Pure Imām called me: ‘Oh Abu Bakr! Bring me the book with the red cover.’ So I brought it to him, and he said, ‘Light a lamp.’ After that, he began to read to the Khalifa. While I was polishing the lamp I heard him say, ‘The Divine Command that entails the life of religion will be carried out only by ʿAbd al-Muʾmin Ibn Ali, Sirāj al-Muwaḥḥidīn (Lamp of the Almohads). The Khalifa wept at hearing these words and said, ‘Of faqih, I know nothing of this. I am only a man seeking that which will cleanse me of my sins’. The Infallible One said to him, ‘The cleansing of your sins is the restoration of the world by your hand.’ Then he gave him the book and said, ‘Blessed are the people you will lead, and accursed are they who oppose you, from the first of them to the last. Great is he who invokes God. God will bless you in life, guide you, and purify you from your fears and worries’.”

'Abd al-Mu'min's claimed descent operated on dual registers. Patrilineally, he traced ancestry to the Arab tribe of Qays through the Banū Sulaym, fulfilling a prophetic ḥadīth stating that the restorer of Islam would come from Qays. Matrilineally, however, he claimed descent from Gannuna bint Idrīs II, linking him directly to Idrīsid sharīfian lineage. His birth in Tlemcen was itself connected to the legacy of Muhammad ibn Sulayman, nephew and companion of Idrīs I who had accompanied him alongside Rāshid, grounding 'Abd al-Mu'min's presence in that city within a deep Idrīsid genealogy of migration and settlement. These genealogical claims, whether historically verifiable or strategically constructed, were politically decisive: in a Maghribi context where even the Ṣanhāja Murābiṭūn claimed affinity with the Ḥimyar Arabs, the association of leadership with both Arabian lineage and Idrisid sanctity proved doubly operative.

From Mallala, Ibn Tūmart and his growing following moved to Fez, the Idrīsid capital. At the Qarawiyyīn mosque complex, he taught what sources describe as Ashʿarī doctrine, directly challenging the Mālikī scholarly establishment. The response was swift: accused of teachings that would "ruin the minds of the masses," he was expelled from the city. This expulsion is significant not for its severity—he was not imprisoned or executed—but for what it reveals about the nature of the threat he posed. Fez, a center of both Mālikī jurisprudence and emergent Sufi networks like the Ḥarāzimī Rābiṭa, could not absorb Ibn Tūmart's challenge without risking an alliance between doctrinal critique and spiritual authority that might destabilize Murābiṭūn legitimacy.

The final urban confrontation occurred in Marrakesh itself, where Ibn Tūmart established himself at the Mosque of the Earthen Minaret and began delivering lectures on uṣūl al-dīn and kalām. The crisis came when he and his companions encountered the sister of Sultan ʿAlī ibn Yūsuf ibn Tāshfīn unveiled in the street, accompanied by veiled male guards in the Ṣanhāja Tuareg fashion. Ibn Tūmart admonished them with ḥadīths prohibiting members of opposite sexes from resembling each other, and when ignored, his followers threw stones until the royal group was forced to retreat. This was not merely moral correction; it was a public challenge to the symbols of Almoravid power.

At this stage, Mahdism remained unnecessary. Ibn Tūmart's authority operated through iṣlāḥ (correction), imtiḥān (examination), and ḥukm (judgment), exercised through an Ashʿarī–Niẓāmiyya grammar foreign to Murābiṭūn intellectual culture. He functioned as a measuring rod applied to an order whose legitimacy had never been compelled to justify itself discursively. Only when this challenge failed to unsettle an authority grounded in territorial unity, Mālikī orthodoxy, and inherited sanctity did a more radical claim become structurally conceivable.

3. The Mālikī–Ashʿarī Fault Line

The confrontation that crystallized around Ibn Tūmart did not originate in administrative failure or political dissent, but in a challenge to doctrinal authority articulated through lived disputation. The Murābiṭūn caliphate, despite its territorial integration and juridical coherence, operated within a Mālikī framework that had never required systematic public articulation of belief. Orthodoxy functioned through precedent, communal practice, and judicial continuity, resting on the assumption that doctrinal correctness was inherited rather than debated. Ibn Tūmart's arrival disrupted this equilibrium by forcing belief itself into the public arena, transforming what had long remained implicit into an object of scrutiny.

The specific fault line emerged around questions of divine attributes and anthropomorphism (tajsīm). Ibn Tūmart employed a sharp binary opposition: tawḥīd versus tashbīh (divine unity versus corporeal comparison). By accusing Mālikī scholars of permitting anthropomorphic understandings of God—whether through literal readings of ambiguous Quranic passages or through pedagogical tolerance of popular conceptions—he transformed a theological disagreement into a test of orthodoxy. This was not mere scholarly description; it was mobilizing rhetoric that placed opponents in the category of "those who liken God to creation" (al-mushabbihūn), thereby disqualifying their authority to speak on matters of belief.Here's the corrected version with Arabic-first ordering throughout:

Mālikī jurisprudence had historically contained such questions through restraint rather than argument. The dominant position, articulated by Mālik ibn Anas himself, was to affirm the Quranic text bi-lā kayf (without asking how), accepting divine attributes as mentioned in scripture without speculating on their modality. This approach preserved communal unity by avoiding divisive speculation and maintaining focus on legal practice rather than theological dispute. Yet once Ibn Tūmart forced the question into public disputation—demanding that scholars defend their position using the tools of kalām—this restraint appeared not as wisdom but as incapacity.

The munāẓarāt (formal disputations) that took place at Marrakesh and later at Aghmat revealed the structural asymmetry. Ibn Tūmart possessed the discursive instruments—Ashʿarī dialectic, ta'wīl (interpretive methodology), systematic theology—to prosecute his challenge. Mālikī scholars, trained in juridical reasoning and transmission of precedent, lacked an equivalent apparatus for defending belief once it was problematized through kalām. They could appeal to the authority of Mālik and the consensus of earlier generations, but they could not argue doctrine on the terrain Ibn Tūmart imposed. When he asked them to list the sources of truth and falsehood, and they replied that ẓann (opinion) was the basis of legal certainty, he exposed what he framed as their fundamental error: conflating juridical probability with theological certainty.

The political crisis this produced was immediate. Mālikī jurists, alarmed by Ibn Tūmart's growing influence and the destabilizing effect of his public challenges, petitioned Sultan ʿAlī ibn Yūsuf (r. 500–537/1107–1143) to have him executed. Their argument was not merely that he was doctrinally deviant, but that his teachings threatened public order by undermining the authority of established scholars and encouraging disobedience. The charge was framed in Khārijī terms—accusing him of declaring other Muslims unbelievers and justifying rebellion—but the deeper anxiety was that belief had become inseparable from obedience. If Ibn Tūmart's critique stood unanswered, the doctrinal foundations of Murābiṭūn's legitimacy would be exposed as indefensible.

The sultan's decision to release Ibn Tūmart rather than execute him reveals the impossible position the regime faced. Execution risked converting doctrinal defeat into martyrdom. Ibn Tūmart's Idrīsid lineage, his ascetic reputation, and his mastery of kalām meant that killing him would not silence the challenge but amplify it, transforming him into a symbol of learned piety crushed by worldly power. Release, however, deferred the problem without resolving it. Ibn Tūmart left the urban arena—first to the Banī Ḥayḍūs cemetery just outside Marrakesh's walls, then to Aghmat for further debates, and finally under armed escort by Ismā'īl Igīg and one hundred of his kinsmen into the High Atlas mountains. This was not retreat; it was relocation from disputation to mobilization.

The crisis had crossed a threshold: a doctrine that could not defend itself discursively could no longer command obedience morally. Mālikī fiqh could regulate conduct with exceptional effectiveness, yet it lacked a structured language for adjudicating challenges to the foundations of belief once they were posed explicitly in the public sphere. What had functioned as restraint now appeared as evasion; what had been prudence now appeared as vulnerability. Ibn Tūmart had exposed the limits of juridical silence, and the existing order possessed no instrument capable of responding without destabilizing itself. What followed was not Ibn Tūmart's defeat, but his transformation—from urban examiner to mountain prophet.

4. Geography as Vulnerability

The political geography of Almoravid Morocco was structured around three competing tribal configurations, each occupying distinct ecological and economic zones. The Ṣanhāja, desert-based and Saharan-oriented, controlled trans-Saharan trade networks and military corridors extending from the Niger and Senegal rivers northward through Morocco and into al-Andalus. The Masmūda, mountain-based in the High and Anti-Atlas ranges, maintained highly localized social structures, defensive mobility, and cultural autonomy grounded in mountain agriculture and pastoral economies. The Barghawāṭa and related Ṣanhāja groups, positioned along the Atlantic plains, had developed heterodox Islamic practices that the Murābiṭūn regarded as heretical and subsequently suppressed through violent conquest.

Marrakesh, founded circa 462/1070 by Yūsuf ibn Tāshfīn (r. 453–500/1061–1106), represented a strategic compromise shaped by these tribal geographies. Its location at the northern edge of the High Atlas secured several advantages: proximity to trans-Saharan caravan termini, control over agricultural production in the Ḥawz plain, and a central position for coordinating military campaigns into both al-Andalus and the deeper Sahara. The site appeared neutral—a plain between tribal worlds—and offered logistical efficiency for an expanding empire. Yet this placement embedded Ṣanhāja sovereignty within Masmūda territory, creating a structural vulnerability that would remain latent only so long as the mountain confederation remained politically inactive.

The alternative—establishing the capital on the Atlantic coast within Ṣanhāja-affiliated zones—had been foreclosed by the Almoravid campaigns against the Barghawāṭa. These populations, concentrated in the Tāmesna plain and along the Atlantic littoral, had developed distinctive religious practices that diverged sharply from Mālikī orthodoxy. The Murābiṭūn suppression of the Barghawāṭa between approximately 453-473/1060-1080 was not merely military conquest but religious extirpation, leaving the region militarily pacified yet politically radioactive. Tribal loyalty there had been destroyed rather than secured; the massacres precluded the establishment of a capital that would depend on local support and agricultural surplus. The Atlantic coast offered maritime access and commercial advantages, yet it could not provide the social foundation for stable rule.

Marrakesh was thus chosen not because it was tribally secure, but because all other options were more dangerous. The capital functioned as a foreign implant in Masmūda lands—administratively effective yet socially unanchored. This worked so long as Masmūda networks accepted Ṣanhāja rule or remained fragmented enough to pose no collective challenge. The ribāṭ system, mediating between central authority and local populations through Idrīsid sanctity and ascetic discipline, helped stabilize this arrangement by providing sites where Mālikī orthodoxy acquired local legitimacy. Yet the geographic contradiction remained: Ṣanhāja sovereignty operated from a position of maximal exposure to the very confederation whose demographic depth and mountain mobility could, if mobilized, transform Marrakesh's hinterland into a zone of siege.

Geography did not doom the Murābiṭūn; it established the terrain on which political contestation would unfold once legitimacy was challenged. A capital embedded in Masmūda territory could be governed from successfully, but it could not be defended against a Masmūda mobilization that converted social infrastructure into military advantage. Ibn Tūmart's later establishment of his ribāṭ at approximately thirty kilometers south of Marrakesh, deeper into the High Atlas, would activate this latent vulnerability by demonstrating that proximity to the capital could function as encirclement rather than subordination. The geography that had enabled Almoravid expansion—centrality, trade access, military reach—became the geography that limited Almoravid resilience once authority was contested from within the mountain zone itself.

5. The Ribāṭ of Tinmal

The transition to Mahdism did not mark a rupture in Ibn Tūmart's trajectory so much as the exhaustion of all lesser instruments of authority. Once doctrinal critique, pedagogical superiority, and sharīfian presence failed to dislodge an order grounded in territorial unification, Mālikī orthodoxy, and inherited sanctity, a totalizing claim became structurally available and politically efficient. Mahdism emerged as a method rather than a vision of eschatological transformation: a technology for collapsing belief, obedience, and command into a single, non-negotiable principle that could override juristic debate, tribal mediation, and inherited legitimacy in one decisive move.

The concept of tawḥīd—divine unity—functioned in Ibn Tūmart's discourse not merely as theological doctrine but as a comprehensive criterion (mīzān) by which both beliefs and authorities could be measured. This transformation from creed to standard was the key to the entire project. If God's oneness was absolute and indivisible, then the community acknowledging it must likewise be unified in belief, practice, and command. Fragmented authority, competing juridical schools, and doctrinal ambiguity all represented failures of tawḥīd when understood as a governing principle rather than an abstract theological proposition. The movement's self-designation as al-Muwaḥḥidūn—the Unitarians—signaled this dual claim: affirmation of God's absolute unity in doctrine, and enforcement of political unity as its necessary consequence.

The choice of Tinmal, in the High Atlas south of Marrakesh, as the institutional center of this transformation was strategically calculated before it was symbolically meaningful. Tinmal is not an abstract mountain retreat but a Masmūda-oriented geography situated approximately thirty kilometers from Marrakesh—close enough to exert constant pressure on the capital while remaining anchored in upland terrain where Masmūda networks and mountain mobility constituted advantages rather than constraints. Its proximity mattered: the movement did not withdraw from power but positioned itself beside it, within striking distance of the city that embodied Almoravid sovereignty, yet embedded in social and geographic terrain where Ṣanhāja administrative reach proved limited.

This geographic positioning exploited the Murābiṭūn capital's placement within Masmūda lands, transforming Marrakesh's logistical centrality into a vulnerability. The ribāṭ at Tinmal became a counter-capital: a site of doctrinal production, military organization, and communal discipline positioned to demonstrate that proximity to Marrakesh could function as encirclement rather than subordination. Where the Murābiṭūn state governed through administration and juridical procedure, the Almohad ribāṭ governed through totalized pedagogy and permanent mobilization.

Within the ribāṭ, Mahdism was transmitted not as speculative doctrine but as systematic discipline. The space functioned as what might be termed a creed laboratory: a site where teaching, indoctrination, collective training, and ritual enforcement produced alignment through immersive communal life. Ibn Tūmart's text Aʿazz mā yuṭlab (The Dearest of What Is Sought) was not written for individual contemplation but as part of a pedagogical apparatus designed to standardize belief, regulate conduct, and eliminate deviation before it could crystallize into dissent. The ribāṭ absorbed Ashʿarī kalām, ethical rigor, and elements of institutional taṣawwuf, subordinating them all to a singular authority whose judgments were not examinable because they proceeded from the Mahdī's providential mandate.

Critically, this pedagogy operated bilingually. Ibn Tūmart's creed was taught in both Arabic and Tamazight, with a specialized class of ḥuffāẓ and ṭalaba undertaking its dissemination. This bilingual transmission was not merely pragmatic but constitutive: it allowed the movement to penetrate social strata that Mālikī jurisprudence, transmitted primarily in Arabic through urban scholarly networks, had never fully reached. By teaching tawḥīd in the language of everyday life, the Almohad daʿwa mobilized populations who had previously encountered Islamic authority only through the mediated presence of Mālikī jurists or Idrīsid ribāṭs. The movement thus achieved mass reach without requiring elite filtering, converting linguistic accessibility into political cohesion.

The Mahdī claim itself drew force from Ibn Tūmart's Idrīsid lineage while exceeding it through a claim to providential mandate. In a Moroccan context where sharīfian descent functioned as accumulated moral capital, the combination of ancestry and Mahdism produced double legitimation: Idrīsid lineage supplied inherited credibility and local recognition, while the Mahdī status supplied present absolutism and eschatological urgency. This was not the absent, deferred Mahdism of Twelver Shiʿism, nor the expectational Mahdism of general Sunni tradition. Ibn Tūmart presented himself as a founding leader whose mission was operational and immediate: to restore correct belief, eliminate corruption, and build a righteous polity now, not in some indefinite future.

In this respect, Ibn Tūmart's Mahdism most closely resembled the Fatimid model of a state-founding Mahdī who combined religious and political authority in a single figure. Yet the Moroccan context—tribal, ribāṭ-oriented, and shaped by Idrīsid memory rather than Ismaʿili metaphysics—produced a distinct configuration. Where Fatimid authority depended on esoteric knowledge (bāṭin) and hierarchical initiation, Almohad authority depended on public pedagogy and communal discipline. The ribāṭ replaced the dār al-ḥikma as the site of doctrinal transmission, and Masmūda tribal networks replaced urban Ismaʿili networks as the social infrastructure of expansion.

This structure also reveals the Muwaḥḥidūn escalation of Moroccan Sufi logic. In earlier Moroccan ribāṭs, authority was built on wilāya (sainthood) and baraka, operating through charisma, asceticism, and pedagogical influence without necessarily claiming political sovereignty. Ibn Tūmart captured this logic—the appeal to moral superiority, the creation of disciplined communities, the use of local languages for teaching—but escalated it to the rank of Mahdī, thereby placing spiritual legitimacy not alongside political power but at its very foundation. Where Sufi wilāya mediated between state and society, Mahdism collapsed that distinction, making doctrinal alignment the condition of political inclusion.

The effectiveness of this system explains the speed of Almohad expansion after Ibn Tūmart's death in 524 AH (1130 CE). The ribāṭ had produced not merely believers but cadres trained to treat doctrine as command and command as salvation. Mobilization could proceed rapidly because alignment had been manufactured through total immersion rather than negotiated through juridical consultation. Yet this same intensity sealed the limits of the model. A structure built on permanent exception and unquestionable authority required constant reinforcement and proved difficult to normalize once the founding figure disappeared. The ribāṭ could accelerate history by collapsing legitimacy into presence; it could not routinize authority across generations without diluting the absolutism that made it effective.

6. Revolutionary Organization Before the State

Ibn Tūmart's genius extended beyond doctrinal mobilization to institutional design. He created a framework capable of surviving his death and scaling into empire. The organizational nucleus was al-Jamāʿa al-ʿAshara (the Assembly of Ten), a decision-making body comprising those who first acknowledged him as Mahdī in a cave near his hometown of Iglī-n-Waraghan upon his return from the East. This revolutionary vanguard was modeled explicitly on the Prophet's ﷺ al-Muhājirūn al-Awwalūn (the First Emigrants)—those who abandoned everything to follow divine guidance.

The composition of the Assembly reveals Ibn Tūmart's strategic calculation. All three major Berber confederations were represented—Ṣanhāja, Masmūda, and Zanāta—alongside claims to Qays ʿAylān Arab descent, creating a microcosm of Maghribi diversity unified under Mahdist doctrine. Loyalty flowed from recognition of the Mahdī's mandate, transcending kinship.

ʿAbd al-Mu'min ibn ʿAlī al-Qaysī stood first among them. Al-Baydhaq claims both patrilineal descent from Sulaymān ibn Manṣūr of Qays ʿAylān (through an Andalusian adopted into the Maṭmāṭa Amazighs) and matrilineal sharīfian descent through his mother, Ṭālu bint ʿAṭiyya, from Lalla Gannūna, daughter of Idrīs II. His birth in Tlemcen—called Āghādīr by the Murābiṭūn and second only to Fez in Idrīsid lineage concentration—grounded him in profoundly Moroccan sharīfian geography. The Banū Gannūna clan of the Gumiya tribe held reputation for leadership and learning throughout Tlemcen's hinterlands.

ʿAbd Allāh ibn Muḥsin al-Wansharīsī, known as al-Bashīr, served as chief strategist. He selected the six tribes of the High and Anti-Atlas that would form the Muwaḥḥidūn military-administrative core. His miraculous firāsa (perception) became legendary among the companions. He fell at the Battle of al-Baḥīra (2 Jumādā I 524/11 April 1130). ʿAbd al-Mu'min witnessed his death, concealed his body, and told survivors that al-Bashīr had been "raised to heaven" (rufiʿa ilā al-samā')—transforming catastrophe into divine sign.

Abū Ḥafṣ ʿUmar ibn Yaḥyā al-Hintātī, a Berber shaykh (chief) of the Hintāta tribe of the High Atlas, bore the original name Faska (ʿīd/festivity). As shield-bearer of the Mahdī and among the greatest Almohad military commanders, his leadership reminded Ibn Tūmart of the second Caliph, earning him the honorary name ʿUmar. He became ancestor of the Ḥafṣid dynasty—a Moroccan lineage that ruled Ifrīqiya from Tunis (626-982/1229-1574), extending Muwaḥḥidūn Moroccan authority eastward even after the collapse of the unified empire. He died of plague in 571/1176.

Abū Ḥafṣ ʿUmar ibn ʿAlī al-Ṣanhājī displayed such piety that ʿAbd al-Mu'min refused to appoint him to administrative posts "for fear of tainting him." After his death in 536/1141, his sons held ceremonial precedence in all military processions—sanctity transformed into inherited rank.

Abū al-Rabīʿ Sulaymān ibn Makhlūf al-Haḍratī served as personal secretary to Ibn Tūmart and died at al-Baḥīra 524/1130. Ismāʿīl ibn Yassallālī al-Hazrajī, called Ismāʿīl Igīg, first gained notice by leading one hundred kinsmen to extract Ibn Tūmart from Almoravid pursuit. Later he served as chief judge and battle commander of the Hargha (Ibn Tūmart's own tribe). He sacrificed himself by taking ʿAbd al-Mu'min's place in bed when assassins came—loyalty unto death.

Muḥammad ʿAbd al-Wāḥid al-Sharqī came from Mallala in the Bijāya region and was adopted into the Mahdī's household. His mother financed his journey west with Ibn Tūmart—maternal blessing consecrating revolutionary commitment. Abū ʿImrān Mūsā ibn Tammāra al-Gadmiyūwī served as Amīn al-Jamāʿa (Trustee of the Assembly) and close aide to Ibn Tūmart. He was killed at al-Baḥīra 524/1130.

ʿAbd Allāh ibn Yaʿlatān Tāzī Zanātī served as standard-bearer in three battles and tribal leader (muqaddam) of Ganfīsa. He rejected Almohad doctrine after Ibn Tūmart's death and was killed by his own tribe when attempting to defect to the Murābiṭūn—proof that doctrinal alignment trumped kinship. Abū Yaḥyā Abū Bakr ibn Iggit died at al-Baḥīra 524/1130. His son later governed Córdoba under ʿAbd al-Mu'min—dynasty building through merit.

By 517/1123, armed conflict with the Murābiṭūn had begun. Ibn Tūmart's forces achieved successive victories, eventually besieging Marrakesh itself. Sultan ʿAlī ibn Yūsuf ibn Tāshfīn personally led a massive army from the capital, confronting the Muwaḥḥidūn near a large orchard (bustān, in local Arabic called al-Baḥīra/the pool) before one of Marrakesh's walls.

On 2 Jumādā I 524/11 April 1130, catastrophe struck. The Almoravid forces crushed the Almohad army—killing all except approximately four hundred survivors. Most of al-Jamāʿa al-ʿAshara perished in the slaughter. Al-Bashīr, Abū al-Rabīʿ Sulaymān ibn Makhlūf al-Haḍratī, Abū ʿImrān Mūsā ibn Tammāra al-Gadmiyūwī, and Abū Yaḥyā Abū Bakr ibn Iggit all died that afternoon—four of the original ten wiped out in a single battle.

Ibn Tūmart, already ill, received news of the devastating defeat. His condition worsened rapidly. He died shortly afterward in 524/1130 or 525/1131, never having controlled territory beyond the mountain ribāṭ at Tinmal. His closest companions concealed his death from the broader movement for an extended period—some sources say years—to prevent total disintegration, especially given the catastrophe at al-Baḥīra had occurred mere months earlier.

Before his death, Ibn Tūmart designated ʿAbd al-Mu'min ibn ʿAlī as khalīfa. The surviving companions gave him al-bayʿa al-khāṣṣa (the private pledge) in Ramaḍān 524/August 1130 while concealing the Mahdī's death. Only later—possibly 526/1132 or 527/1133—did the broader Muwaḥḥidūn community give al-bayʿa al-ʿāmma (the public pledge) at the mosque of Tinmal.

Al-Baydhaq's Kitāb al-Ansāb fī Maʿrifat al-Aṣḥāb reveals fifty-two early followers who remained in Egypt and Syria when Ibn Tūmart returned to Morocco. Their names—al-Lakhmī, al-Iskandarānī, al-ʿAbīdī, al-Yamānī, Ibn Hilāl, al-Ḥijāzī, al-Dimashqī, al-Harwī—map an eastern network spanning Alexandria to Herat. Ibn Tūmart's protector in the Mashriq (East) was a jurist named al-Ḥaḍramī; his principal Syrian aides were Faḍl ibn Rāshid, Ḥusayn ibn Janāḥ al-Ḥalabī, and ʿAbd Allāh ibn Fatḥ al-Makkī.

Their placement reveals strategic positioning rather than lack of commitment. Ibn Tūmart's Mahdist claim carried universal scope, never merely Maghribi ambition. The doctrine of tawḥīd (divine unity) recognized no regional boundaries; divine oneness demanded political unity across the entire dār al-Islām (abode of Islam). These fifty-two served as potential infrastructure for expansion eastward—scholarly networks, ideological foundations, a fifth column awaiting the moment.

The Muwaḥḥidūn empire's confinement to the Maghrib and al-Andalus resulted from historical contingency. Ibn Tūmart died before eastward expansion became feasible. ʿAbd al-Mu'min spent decades consolidating the West. By the time Muwaḥḥidūn power peaked, the window had closed—Ayyubid Egypt, succession crises, and logistical limits redirected energy inward.

The eastern network reveals the original scope: Ibn Tūmart intended an Islamic restoration reaching Damascus, Baghdad, and beyond. The Assembly of Ten functioned as revolutionary cell; the fifty-two in the East served as advance guard; the ribāṭ at Tinmal operated as prototype, never final form. What ʿAbd al-Mu'min built—makhzan, empire, administration—translated a universal project into Maghribi reality.

ʿAbd al-Mu'min thus inherited a shattered movement: the Mahdī dead, most of al-Jamāʿa al-ʿAshara killed, the army destroyed, and the Murābiṭūn state triumphant. That he rebuilt from this ruin into an empire spanning three regions demonstrates extraordinary political skill—yet it also explains why he turned to his Zanāta kinship networks from Tlemcen. The original Masmūda coalition lay in ruins. The project required reconstruction from the ground up, and ʿAbd al-Mu'min rebuilt it around those he could trust through kinship when doctrinal loyalty had proven catastrophically insufficient at al-Baḥīra.

7. ‘Abd al-Mu’imin Conquest and Consolidation (541-558/1147-1163)

After receiving al-bayʿa al-ʿāmma (the public pledge) at Tinmal in 526/1132 or 527/1133, ʿAbd al-Mu'min faced the task of translating Mahdist mobilization into territorial control. His strategy proved methodical. He avoided repeating the catastrophic frontal assault that had destroyed the army at al-Baḥīra, instead employing guerrilla tactics: raiding Almoravid villages, disrupting supply lines, accumulating resources through targeted operations while avoiding pitched battles that might invite disaster.

He exploited Almoravid vulnerabilities systematically. The ruling dynasty faced mounting pressure in al-Andalus as Christian kingdoms advanced southward. Natural disasters compounded instability: a catastrophic flood struck Tangier in 532/1138, and mass emigration from the Maghrib to al-Andalus occurred in 535/1141 as populations fled deteriorating conditions. During this window, ʿAbd al-Mu'min conquered: Darʿa, Sūs, Sijilmāsa, Wādī Warghah. By late 535/1141, Muwaḥḥidūn strength had grown substantially, and momentum shifted decisively.

In 539/1144, he launched major offensives against Murābiṭūn forces commanded by Tāshfīn ibn ʿAlī. Battles lasted two months and ended with Almohad victories at Tlemcen, then Wahrān. At Wahrān, Tāshfīn ibn ʿAlī was killed in combat—a blow that collapsed Almoravid command structure across the Maghrib. As Almohad armies marched toward Marrakesh, the Murābiṭūn dynasty fragmented internally. Isḥāq ibn ʿAlī deposed his nephew Ibrāhīm ibn Tāshfīn and seized what remained of central authority, creating chaos that facilitated Muwaḥḥidūn advance.

ʿAbd al-Mu'min secured the north methodically: Fez, Salé, Sabta. In early 542/1147, he besieged Marrakesh for nine months. The city fell at the beginning of that year. Almoravid princes, including the young Isḥāq, were executed—standard practice for eliminating rival claimants to sovereignty. Simultaneously, the Murābiṭūn Andalusi fleet commander, ʿAlī ibn ʿĪsā ibn Maymūn, submitted to ʿAbd al-Mu'min and pledged allegiance, transferring naval power to Almohad control. A dynasty that had ruled for a century ended.

The consolidation of Muwaḥḥidūn power required dismantling Almoravid legitimacy structures. Mālikī scholars who had provided juridical authorization for the previous regime faced systematic neutralization through political rather than violent means. ʿAbd al-Mu'min invited prominent ʿulamā' to recognize Almohad authority and undergo examination of their doctrinal positions. Some, like ʿAlī ibn Ḥarzihim (d. 559/1163), were released after demonstrating submission. Abū Bakr ibn al-ʿArabī faced trial in Marrakesh, was released, and died shortly in Fez in 543/1148 of natural causes. Others received house arrest: Qāḍī ʿIyāḍ (who died in confinement in 544/1149), Ibn Barrajān (d. 536/1141), al-Suhaylī (d. 581/1185), and Ibn al-ʿArrīf (d. 536/1141). This approach removed scholars from public influence without creating martyrs whose deaths might rally opposition. Their moral authority was eliminated through isolation, demonstrating calculated pragmatism.

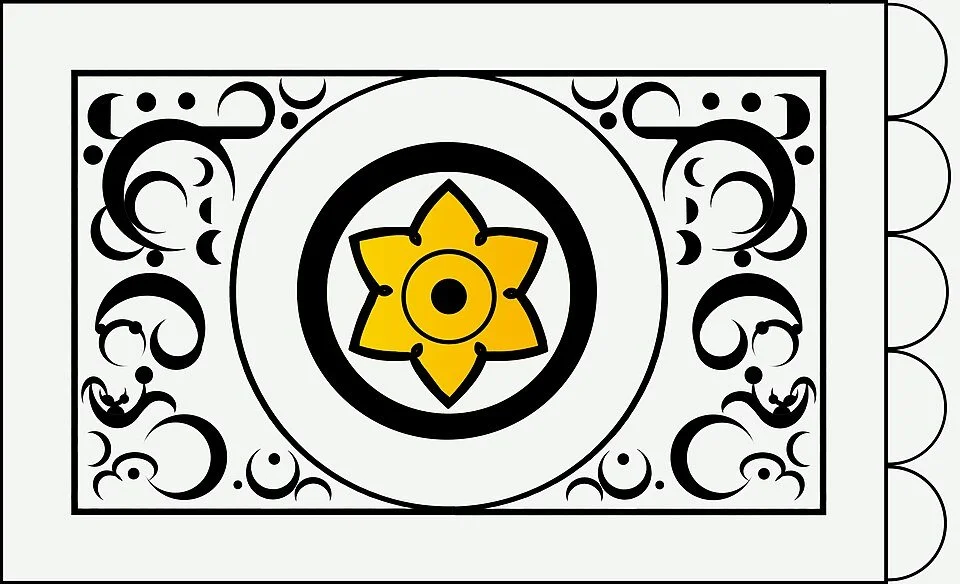

Mural depiction of the white banner of the Muwaḥḥidūn (Almohads) during the defense of Mayurqa (626–627/1228–1231), showing half-moon symbols and a central floral emblem resembling Narcissus jonquilla. The banner represents Almohad sovereignty and jihād authority in al-Andalus, confronting the Aragonese invasion led by James I (r. 609–672/1213–1276). Despite the fall of Mayurqa in 627/1229 and the death of the Almohad governor Abū Yaḥyā, the imagery preserves the visual language of Almohad legitimacy and resistance.

The Muwaḥḥidūn regime also eliminated the ahl al-dhimma (protected non-Muslim) status that had characterized earlier Islamic rule in the Maghrib and al-Andalus. ʿAbd al-Mu'min granted a seven-month grace period, then required Jews and Christians to choose: convert to Islam, emigrate, or face consequences. This policy targeted strategic threats during the Crusade era—Jewish communities integrated into Almoravid economic networks (finance, trade, tax collection) and Christian populations potentially aligned with Reconquista kingdoms actively reclaiming Iberian territory. Most chose conversion or peaceful emigration; figures like Mūsā ibn Maymūn (Maimonides) left for Ayyubid Egypt, where he immediately prospered as court physician to Ṣalāḥ al-Dīn—undermining later accounts of persecution that have been instrumentalized by modern Zionist historiography. The forced conversions addressed wartime security: dismantling Almoravid infrastructure and neutralizing potential collaborators while Crusader states carved up the Levant and Christian kingdoms pressed southward in Iberia.

With Marrakesh secured and the Andalusi fleet under his command, ʿAbd al-Mu'min recovered territories lost during al-Murābiṭūn collapse. His armies moved across al-Andalus: Ronda, Labla, Mértola, Silves, Beja, Badajoz. Seville became the Almohad capital in Iberia, anchoring authority across the southern peninsula. Málaga fell, then within two years Jaén, Córdoba, and Granada. The Almohad reconquest reversed Christian gains and re-established Muslim control over approximately half of al-Andalus.

Simultaneously, he directed eastern expansion into Ifrīqiya. In 548/1153, Muwaḥḥidūn forces entered Bijāya. ʿAbd al-Mu'min personally led campaigns southward, taking Tunis by force (ʿanwatan), then al-Mahdiya (held by Christians), the island of Jerba, Tripoli, and the Ifrīqiyan coast. By 555/1160, his armies had expelled Christians from Tozeur, Bilād al-Jarīd, and Gafsa, completing conquest of the eastern Maghrib. The empire stretched from Tripoli to the Atlantic, incorporating all of Morocco, northern modern Algeria, Tunisia, western Libya, and roughly half of al-Andalus. The Almohads became the first power to unify the entire Maghrib—excluding only Barqa and territories eastward toward Egypt.

“ʿAbd al-Mu’min ruled with wisdom and righteousness. He excelled among the Almohads in virtue, knowledge, piety, and horsemanship. White-skinned with reddish cheeks, dark eyes, tall stature, long fine eyebrows, an aquiline nose, and a thick beard, he was fluent in speech and deeply familiar with the sayings of the Prophet ﷺ. Well-read and learned in matters of faith and worldly affairs, he mastered grammar and history. His morals were beyond reproach and his judgment sound. A generous warrior, enterprising and imposing, strong and victorious, he never—through God’s help—attacked a country without capturing it, nor an army without vanquishing it. He was particularly fond of men of letters and scholars, and was himself a skilled poet. Infallible in judgment as he was powerful, he was so modest that he gave the impression of possessing nothing. He liked neither diversions nor distractions and never rested. The whole of al-Maghrib became subject to him, and al-Andalus fell into his hands. From the Christians he took Mahdiya in Ifrīqiya and Almería, Évora, Baeza, and Badajoz in al-Andalus.”

As ʿAbd al-Mu'min consolidated authority following Marrakesh's conquest, he faced a structural reality: kinship remained the most reliable basis for trust and command in governing a vast empire. His solution was systematic redistribution of power. He distanced Masmūda tribes—who had formed Ibn Tūmart's original base—from positions of real authority and elevated Arab tribes, particularly Banū Hilāl and Banū Sulaym, alongside members of his own Zanāta confederation. He assigned his Kūmī tribe as personal guard, creating protective insulation from potential rivals.

This restructuring became urgent after Ibn Tūmart's brothers, ʿĪsā and ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz, attempted to overthrow him in 549/1154. The revolt failed, demonstrating that even familial ties to the Mahdī carried no automatic legitimacy once ʿAbd al-Mu'min controlled state apparatus. Survivors of al-Jamāʿa al-ʿAshara (the Assembly of Ten) received ceremonial honors—Abū Ḥafṣ ʿUmar al-Hintātī remained prominent until death in 571/1176, and sons of Abū Ḥafṣ ʿUmar al-Ṣanhājī (who died 536/1141) held precedence in military processions—yet real power concentrated in Zanāta hands.

The pattern mirrored what had come before: just as Ibn Tūmart replaced Almoravid Ṣanhāja dominance with Masmūda mobilization, ʿAbd al-Mu'min now elevated Zanāta allies. Doctrinal purity, which had justified overthrowing Almoravids for relying on tribal solidarity rather than tawḥīd (divine unity), gave way to dynastic calculation. The Muwaḥḥidūn empire, built on transcending kinship through belief, reconstituted itself through kinship networks professing correct doctrine. This established a destabilizing precedent: each subsequent caliph would attempt rebuilding coalitions around his own base, eroding doctrinal cohesion that had enabled initial mobilization.

In 558/1163, ʿAbd al-Mu'min prepared for his most ambitious campaign: crossing the Mediterranean to eliminate Christian kingdoms of Iberia entirely. He left Marrakesh at the head of massive armies and reached Ribāṭ al-Fatḥ (Rabat) in Salé. The plan divided forces into four divisions targeting Coimbra (Portugal's capital), Fernando de León, Alfonso VIII of Castile, and Barcelona simultaneously.

The campaign never materialized. ʿAbd al-Mu'min fell suddenly ill and died on 15 Jumādā II 558/1163 at Salé. His thirty-four-year reign ended. He had transformed a movement shattered at al-Baḥīra into an empire controlling all of Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, western Libya, and approximately half of al-Andalus. Ibn Tūmart had died controlling nothing beyond Tinmal; ʿAbd al-Mu'min left an empire unprecedented in Maghribi history, making him one of Morocco's greatest rulers of the twelfth century.

Yet succession immediately proved unstable. He designated his son Muḥammad as heir—a choice reflecting dynastic logic. Muḥammad proved unfit: reckless, afflicted with leprosy (judhām), known to drink wine. He ruled briefly before the Almohad elite deposed him and installed his brother Abū Yaʿqūb Yūsuf. The ease with which succession was contested revealed what ʿAbd al-Mu'min's brilliance had temporarily obscured: Mahdism provided no stable mechanism for transmitting authority across generations. The empire would endure another century, yet fragility embedded in its foundations—tension between doctrinal absolutism and pragmatic governance, between revolutionary origins and dynastic rule—would define its trajectory toward eventual collapse.

8. The Almohad Zenith - Makhzan, Culture, and Imperial Reach (558–595/1163–1199)

Abū Yaʿqūb Yūsuf inherited an empire at its territorial peak. His reign focused on administrative consolidation, cultural patronage, and maintaining the conquests his father had achieved. He continued military campaigns in al-Andalus, pressuring Christian kingdoms and defending Almohad territories, yet his most enduring contributions lay in transforming the Muwaḥḥidūn court into a center of learning rivaling Baghdad and Cairo.

The caliph surrounded himself with philosophers, physicians, and scholars. Ibn Ṭufayl served as his personal physician and introduced him to the works of Aristotle and Greek philosophy transmitted through Arabic translation. More significantly, Ibn Ṭufayl brought the young Ibn Rushd (Averroes) to court, initiating a period of unprecedented philosophical patronage. Abū Yaʿqūb commissioned Ibn Rushd to write commentaries on Aristotelian texts, seeking to reconcile Greek rationalism with Islamic theology. These commentaries would later profoundly influence European scholasticism, transmitted through Latin translations in the thirteenth century.

This intellectual openness created tension with conservative Mālikī ʿulamā' who viewed philosophy as threatening to orthodox belief. Abū Yaʿqūb navigated this carefully, maintaining philosophical inquiry within court circles while avoiding public endorsement that might alienate the juridical establishment whose support remained essential for governance. The balance held during his reign, allowing rational speculation to flourish without provoking the kind of doctrinal crisis that could destabilize the regime.

Abū Yaʿqūb died in 580/1184 during a campaign against Portuguese forces at Santarém, wounded in battle and succumbing shortly thereafter. His death transferred power to his son Yaʿqūb, who would preside over the empire's greatest military triumph and most visible cultural achievements.

Yaʿqūb inherited the title al-Manṣūr (the Victorious) after his decisive victory at the Battle of al-Arak (Alarcos) in 591/1195, where Almohad forces crushed a coalition of Christian kingdoms led by Alfonso VIII of Castile. The battle represented the zenith of Almohad military power in Europe, temporarily reversing Christian advances and demonstrating that the empire could still project force effectively across the Mediterranean. Yet al-Manṣūr's most enduring legacy lay in the creation of makhzan (state apparatus) as a comprehensive system of governance, ceremony, and cultural production.

If ʿAbd al-Mu'min had built the territorial empire, al-Manṣūr gave it institutional form and aesthetic coherence. The term makhzan—initially denoting treasury or storehouse—evolved under his reign to designate the entire complex of centralized administration, fiscal management, military organization, ceremonial protocol, and cultural patronage that distinguished state power from tribal leadership or ribāṭ discipline. The makhzan became visible through material culture as much as administrative procedure.

Muwaḥḥidūn officials adopted distinctive dress codes that marked their status. The Moroccan qafṭān (caftan)—a specific style of robe associated with al-Manṣūr's court—became recognized as makhzan attire, distinguishing courtiers and administrators from common subjects. Court ceremony was regulated and hierarchized, creating a grammar of precedence and protocol that made power legible through ritual performance. Seating arrangements, order of procession, forms of address, and gestural etiquette all communicated rank within the administrative hierarchy. This was governance made visible: authority announced through clothing, movement, and spatial positioning before any words were spoken.

Cuisine became refined and codified, transforming courtly dining into a marker of sophistication and an instrument of patronage. Muwaḥḥidūn court kitchens developed elaborate preparations that distinguished elite consumption from common sustenance, incorporating ingredients and techniques that signaled membership in the ruling class. Meals served political functions, creating occasions for negotiation, alliance-building, and displays of wealth that reinforced hierarchy.

Most distinctively Muwaḥḥidūn was the institutionalization of al-qirāʾa al-jamāʿiyya (collective Quranic recitation). Unlike the individualized recitation traditions that dominated Mālikī practice, the Almohads organized synchronized group recitation sessions that functioned simultaneously as doctrinal reinforcement, communal discipline, and public display of tawḥīd (divine unity). This practice transformed the Quran from a text transmitted through individual chains of authority into a performance of collective unity mirroring their theological insistence on absolute divine oneness. The synchronized voice reciting God's word became a sonic manifestation of Muwaḥḥidī principles: unity in belief producing unity in practice, both publicly performed.

The Muwaḥḥidūn court also elevated malhūn (vernacular poetry), composed in Moroccan dārija (vernacular Arabic) rather than classical fuṣḥā (classical Arabic). This created a distinctively Moroccan poetic voice that made court culture accessible beyond Arabic-literate elites. Malhūn would outlast the dynasty itself, migrating from palace to zāwiya and marketplace, embedding Almohad cultural innovations into Moroccan society long after the state collapsed.

Al-Manṣūr's architectural program transformed the Maghribi and Andalusi landscape into a canvas for projecting Almohad authority. These structures shared a common architectural vocabulary: monumental vertical scale, geometric precision reflecting tawḥīd theology, and axial symmetry manifesting cosmic order under singular divine and political authority.

Jāmiʿ al-Kutubiyya (the Koutoubia Mosque) in Marrakesh, founded by ʿAbd al-Mu'min in 542/1147, established the template. Its seventy-seven-meter minaret dominated the city skyline, visible for kilometers in all directions. The tower's square base, sebka (diamond lattice) decoration, and internal ramp system (allowing riders on horseback to ascend) became signature elements of Almohad design.

Manārat al-Khīrālda (the Giralda) in Seville, begun during ʿAbd al-Mu'min's reign in the 544/1150s and completed under his successors, rose to one hundred and four meters. The tower still stands today, testifying to Almohad engineering and aesthetic achievement. Seville functioned as the Muwaḥḥidūn capital in al-Andalus, and the Giralda announced that authority across the Mediterranean from a structure whose height exceeded anything Christian kingdoms had built in Iberia.

Burj al-Dhahab (the Torre del Oro/Tower of Gold) in Seville served military and symbolic functions simultaneously. This dodecagonal watchtower controlled naval access to the city via the Guadalquivir River, its golden tiles giving the structure its name while making Muwaḥḥidūn surveillance visible to all who approached by water.

Under al-Manṣūr, the most ambitious project began: Ṣawmaʿat Ḥassān (the Hassan Tower) in Rabat, initiated around 593/1197. Had it been completed, the minaret would have exceeded sixty meters as part of the largest mosque complex in the western Islamic world. Al-Manṣūr's death in 595/1199 halted construction, leaving the tower incomplete—a monument to ambition that exceeded the dynasty's endurance. The unfinished structure nevertheless demonstrated the scale of Almohad architectural vision.

Bāb al-Udāya (the Ceremonial Gate of the Kasbah of the Udayas) in Rabat, added by al-Manṣūr in the late 1190s/590s, transformed the fortress ʿAbd al-Mu'min had established into a monumental entrance announcing imperial authority. The gate's refined stonework, monumental proportions, and decorative program made state power legible through architecture.

These structures collectively created an Muwaḥḥidūn architectural identity: three great minarets (Koutoubia completed, Giralda completed, Hassan incomplete) forming an unfinished trilogy spanning the empire from Marrakesh to Seville to Rabat. All employed square bases, sebka decoration, internal ramps, and heights ranging from sixty to over one hundred meters. The vertical assertion of authority made Almohad sovereignty visible across urban landscapes, announcing makhzan presence before any administrative decree was issued.

The intellectual flourishing that had begun under Abū Yaʿqūb Yūsuf continued into al-Manṣūr's early reign. Ibn Rushd remained at court, producing his major philosophical works including commentaries on Aristotle that would shape European thought for centuries. The Muwaḥḥidūn court library collected manuscripts from across the Islamic world, and scholars found patronage that enabled sustained intellectual production.

Yet this openness remained conditional and tactical. The critical moment came in 591/1195, when al-Manṣūr prepared for the decisive confrontation with Alfonso VIII of Castile at Alarcos. Andalusi Mālikī ʿulamā', whose support was necessary for military mobilization against Christian forces, remained hostile to philosophy, viewing it as incompatible with orthodox Sunnī belief. Al-Manṣūr faced a choice: retain philosophical patronage and risk alienating the juridical establishment he needed for the campaign, or sideline philosophy to secure ʿulamā' support.

He chose battlefield victory. Ibn Rushd was removed from court, his works placed under scrutiny, and philosophical teaching curtailed. The Almohad triumph at Alarcos—which earned al-Manṣūr his title and temporarily halted Christian advances—came at the cost of intellectual openness. The decision revealed that even a regime built on doctrinal innovation could not afford to alienate conservative juridical opinion when political survival was at stake. Philosophy had been permitted so long as it remained politically costless; once it threatened to undermine the coalition necessary for military success, it was sacrificed.

Ibn Rushd died in 595/1199, the same year as al-Manṣūr, symbolically closing the era of Almohad philosophical patronage. His works survived through transmission to Europe via Latin translation, where they influenced Thomas Aquinas and the development of scholasticism, yet within the Almohad empire, falsafa never recovered the prominence it had briefly enjoyed. The regime's relationship to rationalist thought proved tactical rather than structural, deployed when useful and abandoned when inconvenient.

The Muwaḥḥidūn empire's reach extended beyond the Maghrib and al-Andalus into strategic alliance with the Ayyubid dynasty in the Levant. The Crusader presence in Jerusalem and the coastal Levant represented a shared Sunnī concern, and the Almohads provided naval and military support for Ayyubid campaigns against Crusader states. This cooperation culminated in support for Ṣalāḥ al-Dīn al-Ayyūbī (Saladin) during the period leading to the Battle of Ḥiṭṭīn in 583/1187, where Ayyubid forces decisively defeated the Crusader army and recaptured Jerusalem.

Muwaḥḥidūn naval power in the Mediterranean enabled the transport of supplies, troops, and material support to Ayyubid territories. The fleet that ʿAbd al-Mu'min had built and that his successors maintained provided strategic depth for Sunnī resistance to Crusader expansion. Ṣalāḥ al-Dīn's reported statement—"Lā athiqu illā bi-l-Maghāriba" ("I trust no one but the Moroccans")—reflected the reliability of Almohad support during a period when other Muslim powers pursued fragmented and often competing interests.

This alliance represented the peak of Muwaḥḥidūn prestige. From the Atlantic to Palestine, the empire functioned as a pillar of Sunnī power, projecting authority across three continents and coordinating with the most successful Muslim military leader of the era. The Almohads were recognized as essential partners in the defense of Islamic territories against Christian expansion, demonstrating that their reach exceeded regional Maghribi concerns and extended into the strategic calculations of the broader Islamic world.

Yet this moment of maximum extension also marked the empire's zenith. Al-Manṣūr died in 595/1199, and with his death, the combination of military success, architectural ambition, and trans-regional alliance began to unravel. The structures he had built—institutional, cultural, and political—would outlast him, yet the cohesion that had sustained them depended on continuous successful leadership and military victory. Once either faltered, the fragility embedded in Muwaḥḥidūn foundations would become apparent.

9. The Unraveling of Legitimacy (595-668/1199-1269)

The Muwaḥḥidūn collapse reveals a fundamental mismatch between doctrine and geography. Ibn Tūmart's tawḥīd was conceived as universal principle—God's oneness admits no regional variation, no compromise with local practice, no accommodation of difference. This universalism made rapid expansion possible: the doctrine traveled because it claimed to transcend place. The Almohads conquered from Tripoli to the Atlantic precisely because their message denied the legitimacy of regional particularism. Every existing authority structure—Almoravid, Mālikī, Idrīsid—was delegitimized as deviation from singular truth.

The problem emerged when universal doctrine had to govern particular places. Al-Andalus required perpetual military mobilization against Christian kingdoms. Ifrīqiya demanded management of Mediterranean trade networks and diplomatic relations with Italian maritime republics. Morocco itself contained Amazigh tribal confederations with distinct customary practices, Idrīsid sharīfian networks commanding local baraka (spiritual power), and urban centers where Mālikī juridical tradition remained embedded in social reproduction. Governing this diversity required flexibility that Mahdist absolutism could not provide without undermining its own premise.

The defeat at al-ʿUqāb (Las Navas de Tolosa, 609/1212) exposed this impossibility. The battle mattered less as military event than as revelation of structural limits. If tawḥīd guaranteed divine favor, and divine favor manifested in victory, then defeat announced either doctrinal failure or leadership corruption. No third interpretation existed within the Mahdist framework. The regime could not respond by acknowledging that battlefield outcomes reflect contingent factors—logistics, terrain, numerical superiority—because doing so would admit that God's support operates through mundane causation rather than direct intervention. Mahdism had eliminated the space between theology and politics; al-ʿUqāb revealed the cost of that elimination.

Morocco possessed a legitimacy structure predating both Almoravids and Almohads: Idrīsid sharīfian sanctity rooted in prophetic descent and centuries of localized baraka accumulation. The Idrīsids had never governed through Mahdist claims or military conquest. Their authority operated through genealogy, miracle-working, intercession, and embeddedness in regional networks. This was legitimacy as presence rather than doctrine, as inherited sanctity rather than revolutionary mandate.

The Muwaḥḥidūn had marginalized Idrīsid networks during consolidation, viewing them as competitors to Mahdist authority. Ibn Tūmart's doctrine required singular source of legitimacy; Idrīsid sanctity offered distributed baraka operating independently of state control. The regime could not tolerate this alternative precisely because it functioned: communities recognized Idrīsid sharīfs as sources of blessing, mediation, and spiritual guidance regardless of who controlled Marrakesh. This was legitimacy the state could neither monopolize nor eliminate.

As Mahdism weakened after al-ʿUqāb, Idrīsid networks resurged. The assassination of Mawlāy ʿAbd al-Salām ibn Mashīsh around 625-626/1227-1228 and the execution of Muḥammad ibn Yaʿqūb ibn ʿAbd Allāh, who had established an Idrīsid ribāṭ in Āyt ʿĪtāb near Marrakesh, by al-Rashīd (630-640/1232-1242) demonstrate regime response: violence against figures whose sanctity derived from genealogy rather than state appointment. The repression revealed fatal misrecognition. Idrīsid baraka operated through kinship, zāwiya networks, and local devotion—structures that violence could not dislodge because they were embedded in social fabric rather than dependent on individual leaders. Killing sharīfs did not eliminate sharīfian authority; it demonstrated that the regime possessed no framework for coexisting with forms of legitimacy it had not created.

The contrast with Almoravid practice is instructive. The Murābiṭūn had incorporated Idrīsid networks, channeling Mālikism through sharīfian intermediaries like Waggāg ibn Zallū (d. 445/1054). This created mutual reinforcement: Mālikī fuqahā' gained sanctity through association with prophetic descent; Idrīsid sharīfs gained institutional position through juridical competence. The Almohads, demanding doctrinal monopoly, could not pursue this path. By attacking Idrīsid sanctity, they undermined the moral geography that had allowed earlier regimes to govern Morocco without constant coercion.

Idrīs al-Ma'mūn's repudiation of Ibn Tūmart in 626/1228 represented an attempt to solve the Mahdist legitimacy crisis through subtraction. Having conquered Marrakesh with fifteen thousand Christian cavalry provided by Fernando III of Castile—surrendering fortresses, building a church for Spanish troops, stipulating that Christian conversions to Islam be rejected—he confronted the doctrinal problem directly. He removed Ibn Tūmart's name from sikka (coinage) and khuṭba (Friday sermon), eliminated Amazigh liturgical innovations, and declared: "There is no Mahdī except ʿĪsā ibn Maryam (Jesus son of Mary)... This [Ibn Tūmart's claim] was a bidʿa (innovation) which we have removed." He went further, calling Ibn Tūmart and followers kuffār (unbelievers) while retaining the title Amīr al-Mu'minīn (Commander of the Faithful).

The logic appeared straightforward: Mahdism had become obstacle to governance, alienating Mālikī scholars, preventing diplomatic flexibility, and generating succession crises through its inability to routinize charismatic authority. By declaring the doctrine fraudulent, al-Ma'mūn hoped to gain administrative freedom while preserving dynastic claim. The calculation was that administrative competence and military power could substitute for doctrinal legitimacy.

The calculation was wrong. Legitimacy that had been unified and indivisible under Mahdist doctrine became infinitely divisible once the doctrine was withdrawn. Provincial governors who had submitted because the regime claimed divine mandate now possessed no reason to continue obedience once that mandate was declared fraudulent. Abū Zakariyyā' Yaḥyā in Ifrīqiya—himself a Moroccan and descendant of Abū Ḥafṣ ʿUmar al-Hintātī from al-Jamāʿa al-ʿAshara (the Assembly of Ten)—proclaimed independence and founded the Ḥafṣid dynasty (626-982/1229-1574). His reasoning was impeccable: if Ibn Tūmart's claim was false, what bound Ifrīqiya to Marrakesh? Shared administrative practice? Institutional continuity? These were insufficient without the doctrinal framework that had originally unified them.

Al-Ma'mūn's trajectory reveals the impossibility of post-Mahdist legitimacy within the Almohad framework. He died in 630/1232 rushing between military crises, having stabilized nothing. His repudiation accelerated fragmentation rather than arresting it because he had no alternative legitimacy structure to offer. He could not invoke Idrīsid sanctity (having repressed it), could not appeal to Mālikī consensus (having marginalized it), could not claim dynastic right (having declared the dynasty's founder a heretic). What remained was force: Christian mercenaries, executed elders, besieged cities. This was governance reduced to coercion, authority stripped of consent.

The Muwaḥḥidūn trajectory from 524-668/1130-1269 demonstrates that Mahdism functions as inception mechanism rather than inheritance structure. Ibn Tūmart mobilized through crisis: he presented himself as divinely appointed corrector arriving at the moment of civilizational deviation. This claim worked because it addressed a felt need for restoration. The Murābiṭūn had ossified; Mālikism had become rigid; religious practice had deviated from purity. Ibn Tūmart offered return to origins, and his claim was credible precisely because the situation appeared to demand such intervention.

His successors inherited symbols without substance. They possessed the title khalīfa, commanded the administrative apparatus, invoked the Mahdī's memory. They could not credibly claim the same mandate because the crisis that had made Mahdism necessary—or at least plausible—no longer obtained. If Ibn Tūmart had already restored correct belief, what justified continued absolute obedience to descendants who lacked his prophetic recognition? The question had no satisfactory answer within Mahdist logic.

The first seventy years (524-595/1130-1199) succeeded because ʿAbd al-Mu'min, Abū Yaʿqūb Yūsuf, and Yaʿqūb al-Manṣūr could present themselves as preservers and enforcers of the Mahdī's restoration. They governed through Ibn Tūmart's reflected authority, extending his project geographically and institutionally. The claim remained credible so long as expansion continued and military success demonstrated divine favor. Al-ʿUqāb shattered this narrative. Subsequent caliphs (610-668/1213-1269) averaged less than eight years each because succession had become contest resolved through violence rather than transmission governed by recognized principle.

The deeper problem was that Mahdism precludes the very compromises that enable dynastic endurance. Successful dynasties develop mechanisms for managing elite competition, incorporating regional powers, and accommodating doctrinal diversity. The Marinids would later demonstrate this by positioning themselves as restorers of Idrīsid memory rather than as revolutionary correctors. They could negotiate with Mālikī ʿulamā', honor sharīfian lineages, and govern through coalition because they made no claim to absolute doctrinal mandate. The Almohads, bound by their Mahdist origins, could not pursue these paths without repudiating their founding premise—and when al-Ma'mūn attempted precisely that repudiation, the empire dissolved.