The Idrīsid Imamate: From Ancient Morocco to the Ribāṭ Age

Long before Mawlāy Idrīs crossed the mountains into Walīlī (Volubilis), Morocco was already an ancient and self-conscious civilization. To the Greeks, it was the land of the Mauroi; to the Romans, it was Mauretania Tingitana, a kingdom whose rulers negotiated with emperors and whose cavalry rode in distant provinces from Britannia to Syria. The celebrated Juba II—scholar, geographer, and philosopher—reigned here with his queen Cleopatra Selene, daughter of Egypt’s last pharaoh. Their capital at Volubilis stood as one of the great cities of the Mediterranean world, where Roman administration, local Moorish culture, and Hellenistic learning blended into a uniquely Moroccan synthesis. Across the plains and coastal zones, cities like Sala, Tingis, and Tamuda flourished with commerce, agriculture, stone architecture, and maritime trade. Christianity spread early through these regions; bishops and monastic communities became part of the Moroccan landscape. Even the Canary Islands lay within Morocco’s maritime sphere, confirming that this was not a marginal land but a sovereign world with deep cultural roots.

When Islam arrived in the 1st/7th century, it encountered not a tribal vacuum but a society already formed by centuries of statehood, diplomacy, and spiritual traditions. Early Arab commanders, including ʿUqba ibn Nāfiʿ, met communities capable of political negotiation, conversion, and alliance. Islam settled into Moroccan life through teaching, kinship, and gradual integration rather than collapse or destruction. Yet Morocco did far more than adopt Islam; it became the western frontier of the Islamic world and one of its most decisive military actors. Under Ṭāriq ibn Ziyād, Moroccan forces crossed the strait that now bears his name, opening al-Andalus and transforming the history of Europe and the Mediterranean. The conquest of Iberia was not merely an Arab initiative; it was a Maghrebi-led movement, carried by the discipline, courage, and strategic genius of the Amazigh tribes. For the first time, Morocco’s ancient martial energies were directed onto a new civilizational horizon.

This world of cities, tribes, and Islamic expansion was shaken profoundly by the great Berber Revolt of the 2nd/8th century. The decisive confrontation, the Battle of al-Ashrāf, shattered the Umayyad army and severed the line that had once tied Damascus to the Maghrib and al-Andalus. From that moment, the western Islamic world became autonomous. Khārijite emirates—fierce, doctrinal, militarily trained—rose across Morocco. They wielded power, collected taxes, wrote law, and commanded armies, yet they lacked the one ingredient that could unite the land: prophetic legitimacy. The Umayyads could no longer impose authority; the Abbasids, distant and distrusted, held no moral claim over Morocco. The region stood at once strong and ungoverned, ancient and fractured, Islamic yet without a rightful Imām.

Thus, when Mawlāy Idrīs ibn ʿAbd Allāh, grandson of the Prophet ﷺ, survivor of Fakh, and bearer of the Ḥusaynī party described in Al-Ibrīz—the party that upholds the Muhammadan truth when kings betray it—arrived at Volubilis in 172/789, he did not enter chaos or emptiness. He entered a landscape waiting for a moral axis. In the East, the descendants of the Prophet ﷺ had been slaughtered at Karbalāʾ and persecuted at Fakh; but in the West, a people shaped by ancient sovereignty, Christian memory, and new Islamic ethics stood ready to receive a lineage that carried not merely political grievance but the residue of Prophetic authority.

From this point, the tone of history changes. Mawlāy Idrīs was not a fugitive seeking protection; he was the sole surviving standard-bearer of a stalled Islamic revolution, the Zaydi revolt that had tried to rescue the caliphate from tyranny and restore it to the House of Muḥammad ﷺ. His mission in the Maghrib cannot be reduced to a claim for justice or an escape from Abbasid violence. He embodied a messianic possibility, a continuation of the Prophetic project in a world where the East had collapsed under despotism.

In him converged several currents: the Qurashī ancestry that made him heir to the Muhammadan kingdom; the Zaydi ethos that demanded a ruler act or fall; the Ḥusaynī spirit that saw martyrdom as a political testimony; and the Maghribi longing for a unifying, legitimate imam. He arrived not as a stranger but as the culmination of a Prophetic horizon migrating westward. In the meeting between Mawlāy Idrīs and the Awraba chieftains, Morocco’s ancient kingdoms met the surviving remnant of the Prophet’s ﷺ household. The imamate did not begin in Morocco with a refugee; it began with the Muhammadan trust relocating itself to the one land still capable of receiving it.

This is the moment when Morocco ceased being only an ancient country and became—through Mawlāy Idrīs—the custodian of Prophetic legitimacy, the western sanctuary of the Muhammadan line, and the horizon from which many believed the future renewal of Islam would one day rise.

I. The Eastern Lineage of Revolt: From Medina to Fakh

The story of Mawlāy Idrīs ibn ʿAbd Allāh does not begin at Walīlī, nor even with the Abbasid persecution that forced him westward. Its roots lie in Medina, where the earliest fissures of Islamic political life produced a distinct moral tradition within the House of the Prophet ﷺ. This tradition—shaped not by sectarian ideology but by a relentless commitment to justice, transparency, and ethical governance—formed a lineage of principled defiance extending from the first generation of Ahl al-Bayt to the upheavals of the second Islamic century.

After Karbalāʾ, the descendants of Imām al-Ḥasan al-Sibṭ ibn ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib (d. 50/670) emerged in Medina as a quiet but persistent alternative to imperial models of rule. Their patriarch, ʿAbd Allāh al-Kāmil ibn al-Ḥasan al-Ridā (d. 145/762), embodied piety, restraint, and open critique of Umayyad excess. His household preserved a vision of leadership grounded not in conquest but in the moral constitution of Qurʾānic rule. This atmosphere produced a series of ethical revolts, whose aims were not doctrinal separation but restoration of legitimacy. Zayd ibn ʿAlī al-Sajjād (d. 122/740)—great-grandson of Imām al-Ḥusayn ibn ʿAlī (d. 61/680)—initiated the clearest expression of this ethos. His uprising in Kūfa articulated what became the Zaydi imprint: resistance to injustice, insistence on accountability, and the refusal to sanction rulers whose authority contradicted Qur’ānic ethics. Although later Zaydism took on theological contours, Imām Zayd himself fought on ethical grounds, not sectarian ones.

His martyrdom generated successors. Yaḥyā ibn Zayd fell in Khurasan in 125/743. The uprising of al-Nafs al-Zakiyya in Medina signaled the widespread conviction that the caliphate required a leader of prophetic descent to restore justice. Meanwhile, Abbasid promises of supporting Ahl al-Bayt dissolved once they gained power in 132/750. Medina became a monitored zone, and the Hasanids realized that the new dynasty intended not partnership but containment. The House of ʿAbd Allāh al-Kāmil became a symbolic conscience for the Ummah, representing the ethical horizon of the prophetic family in contrast to the increasingly rigid structures of caliphal politics.

Into this genealogy was born Idrīs ibn ʿAbd Allāh, a great-grandson of al-Ḥasan whose political instinct was shaped by the living memory of the Prophet ﷺ and by the intellectual climate of Medina, where Ahl al-Bayt were regarded as the “living essence of knowledge,” to borrow Imam ʿAlī’s terminology. In sermons attributed to him, ʿAlī defines his family as the loci of divine knowledge, the pillars of Islam, the custodians of revelation, and the gates through which the faith must be approached. Such statements were not metaphysical claims; they articulated a political principle: legitimacy and justice were inseparable from the moral authority of the Prophet’s household. Zayd expressed the same ideal in verse, describing Ahl al-Bayt as “the lights before creation” and “the axis of truth.” Idrīs inherited this worldview not as an ideological program but as the natural horizon of a family that had long been treated as the conscience of the Muslim community.

This lineage reached its tragic apex in the massacre of Fakh in 169/786, often called “the second Karbalāʾ.” When al-Ḥusayn ibn ʿAlī al-Ḥasanī rose against Abbasid tyranny near Mecca, he represented the cumulative grievances of decades. The revolt was quickly crushed; the aftermath was brutal. Bodies were left exposed; families terrorized; heads sent to Baghdad. Early Islamic memory treated the event as seismic. Reports circulated that the Prophet ﷺ had foretold a righteous descendant who would be slain at Fakh and whose martyrdom would be doubly rewarded. The moral trauma of the valley near Mecca, where Companions had once walked, became emblematic of Abbasid collapse of legitimacy. Mawlāy Idrīs escaped the battlefield with his brother Yaḥyā, carrying wounds and the certainty that the East could no longer shelter Ahl al-Bayt.

Yet his departure was not merely flight. Yaḥyā is reported to have said to him: “We have a banner that will rise in the West at the end of time. God will manifest the truth through its people. Perhaps it will be you—or a man from your descendants.” This statement—preserved in al-Rāzī’s Akhbār Fakh—and echoed in Moroccan collective memory, reframes Idrīs’s journey as the continuation of a prophetic trajectory rather than the relocation of a defeated partisan.

Two further traditions reinforced this logic. One, preserved by al-Ifrānī and cited from al-Jumān, recounts a prophetic assurance to Lalla Fāṭima al-Zahrā’ that the Berbers would become the helpers of her descendants—the ḥawārīyūn of Ahl al-Bayt—and that when the children of al-Ḥasan and al-Ḥusayn scattered after oppression, only the Berbers would shelter them. The second is the well-known ḥadīth in Muslim: “The people of the West will remain visibly upon the truth until the Hour is established.”

While its exact scope is debated, Maghribi scholars long interpreted it as a spiritual confirmation of the Western role in preserving the integrity of the faith.

By the time Mawlāy Idrīs left Egypt, these strands—Zaydi ethics, Hasanid legitimacy, prophetic foresight, and Maghribi expectation—had begun to converge. He was not only a political survivor; he was the last unbroken thread of a moral tradition that refused to separate governance from righteousness. He carried the heritage of Medina’s ethical protests, the memory of the Prophet ﷺ, the teaching of Imam ʿAlī about the indispensability of Ahl al-Bayt for the Ummah’s guidance, and the Zaydi insistence that an imam must rise against tyranny whenever conditions allowed.

Thus, when Mawlāy Idrīs reached the borders of Morocco, he arrived not as a wanderer seeking refuge but as the embodiment of a lineage that had exhausted the East and now moved toward a new horizon. The Maghrib—after the Moorish Revolt, the collapse of Umayyad authority, and the fragmentation that followed the decisive battlefield of al-Ashrāf—was a land rich in sovereignty but lacking a legitimate axis. In this fractured political landscape, the appearance of a grandson of the Prophet ﷺ was not an accident of geography but the meeting point of prophecy, history, and necessity. The Western imamate began not in a tribal council at Walīlī, but in Medina generations earlier, and Idrīs’s arrival in the Maghrib represented its rightful continuation in a land destined, as many believed, to uphold the truth until the end of days.

2. The Maghrib Before Mawlāy Idrīs

When Mawlāy Idrīs entered the western lands, he encountered a Maghrib already deeply Islamized yet politically fragmented—a condition born directly from the Battle of al-Ashrāf (129/746). In that confrontation, Berber armies destroyed the Umayyad force led by Kulthūm ibn ʿIyāḍ al-Qushayrī, bringing to an end the last serious attempt to restore eastern military authority across the far West. The defeat was not merely tactical; it ended Umayyad military sovereignty in the Maghrib and broke the administrative chain linking Damascus to Ifrīqiya and al-Andalus.

From this moment emerged a series of minor political formations, unified less by shared purpose than by a common refusal of Qurashī authority. The Barghwāṭa confederation (127/744), on the Atlantic plains, founded by Ṣāliḥ ibn Ṭarīf, amounted to a sealed micro-order—doctrinally eccentric, inward-looking, and incapable of regional political integration beyond its immediate territory. In the Rif, the polity of Nakūr (91/709), established by Ṣāliḥ ibn Manṣūr, remained a narrow coastal enclave, sustained by local alliances and maritime traffic, without the means or vision to shape the Maghrib at large. In the far southeast, Sigilmāsa, founded by Samgū ibn Wāsūl under Ṣufrī Kharijite leadership (140/757), functioned as a commercial outpost rather than a state—wealthy through transit, yet structurally incapable of political integration. To the east, the Rustamid polity of Tahert (160/776), founded by ʿAbd al-Raḥmān ibn Rustam, governed a clerical island: morally rigorous, territorially thin, and deliberately limited in ambition.

Beneath these political structures ran a deeper intellectual current shaped by the ethical revolts later articulated within the Muʿtazilite-inflected movements of Imām Zayd, his brother Ibrāhīm (145/76), and Muḥammad al-Nafs al-Zakiyya (145/76). Their uprisings formulated an ethical grammar that took firm root in North Africa: rule is conditional upon justice, authority is accountable, and resistance becomes legitimate once divine equity is violated. This posture—ethical rather than sectarian—found a natural home in the leadership of Abū Layla Isḥāq b. Muḥammad b. ʿAbd al-Ḥamīd, chief of the Awraba, the most powerful branch of the Masmuda.

Long before the Idrīsid settlement, the Awraba had already translated this grammar into action. During the first Islamic openings in Ifrīqiya, they stood at the center of organized resistance, most notably under Kusaila (d. 63/683), whose leadership exposed the limits of Umayyad expansion and imposed heavy costs on commanders such as ʿUqba b. Nāfiʿ. The contrast was stark: while Syria, Iraq, Egypt and Persia entered Islam within a single generation, the Maghrib resisted for nearly seventy years. Yet once this long cycle of coercive expansion collapsed—after the fall of al-Kāhina—the entry into Morocco itself unfolded with minimal resistance, signaling not submission, but a shift toward negotiated legitimacy.

Crucially, unlike the Khārijites who categorically rejected Qurashī leadership, the Awraba maintained an important nuance: they acknowledged that a descendant of the Prophet ﷺ could rightfully rule, provided he embodied justice and moral courage. This predisposition made them uniquely prepared to recognize in Mawlāy Idrīs not a foreign claimant but the very figure whose lineage and biography fulfilled their highest expectations of leadership.

Yet the Maghrib before Mawlāy Idrīs cannot be understood without the parallel transformation taking place across the strait. The establishment of the second Umayyad emirate in Córdoba—often described as Andalusian—was, in its origins, a profoundly Moroccan event. Its founder, ʿAbd al-Raḥmān ibn Muʿāwiya (d. 172/788), the only surviving Umayyad prince, reached safety not in Iberia but in Nakūr, where the Zanāta sheltered him. His mother’s Moorish lineage opened doors no Arab ally could provide, and it was Zanāta cavalry who accompanied him into Andalusia, helped him negotiate alliances, and enabled him to seize Granada and Seveilla. The Umayyad restoration in al-Andalus was therefore not an exilic project from the East but a Berber reconstruction, facilitated—and in many respects engineered—by Moroccan tribes.

This Moroccan presence extended into religious and revolutionary movements as well. The first Shiʿi uprising in the West, led by Muḥammad ibn ʿAbd Allāh al-Miknāsī (fl. 172/789), a native of Miknāsa (a major Berber confederation, preserved toponymically in the name Meknès), ignited a twenty-year rebellion against ʿAbd al-Raḥmān I in al-Andalus. His revolt drew on the same Zaydi ideals that animated Eastern uprisings, further illustrating how Moroccan intellectual and political currents shaped the western Islamic world. It was again the collaboration of Umayyads and their Zanāta uncles that ultimately suppressed this revolution—an early demonstration of the enduring Moroccan imprint on Andalusian affairs.

Taken together, these developments reveal a West that was never peripheral and never derivative. Long before Rome, Carthage had already turned the western Mediterranean into an African sphere, and from that world Hannibal (d. 183 BCE) carried war through Iberia and into Italy itself. Long before Islam, and long after Rome, Morocco pressed itself into Iberia as force, movement, and command. This was already visible in the Roman age through the Mauroi cavalry, most starkly embodied in the Mauretanian general Lusius Quietus (Kitos). Entrusted by Trajan with the suppression of the great Jewish uprisings of 115–117, Quietus led mobile North African forces across Cyrenaica, Egypt, Cyprus, and Mesopotamia, crushing revolts that threatened Rome’s eastern arteries. The very naming of the conflict as the Kitos War inscribes a Moroccan commander into imperial memory, revealing how Maghribi military power was projected far beyond the western Mediterranean.

Lusius Quietus Commanding the Moorish Cavalry, a Cast Taken from Trajan's Column, AD 110-113

Ṭārif ibn Mālik (fl. 91/710), whose name endures in Tarifa, opened the passage as reconnaissance and declaration. He was soon followed by Ṭāriq ibn Ziyād (d. 101/720), whose name came to command the strait itself—Gibraltar—turning a stretch of water into a governed threshold, aided by Julian of Sabta, a Ghumāra Moroccan whose authority was rooted in that corridor. What followed was not improvisation but the opening (al-Futūḥāt) of al-Andalus, conducted within the framework of an Arab-Islamic civilizational project, articulated in Arabic, legitimated by Qurʾānic authority, and led in the name of the Umayyad polity, yet carried on the ground by large-scale Amazigh participation, including sustained Moroccan migration that settled, defended, and administered the peninsula. Along the axis binding Tingis to Baetica, Arab leadership and Maghribi force together shaped conquest, access, and early governance, confirming that al-Andalus emerged as a western extension of Islam, articulated in Arabic, yet materially and structurally formed as a northern extension of the Moroccan world.

It was into this world—politically fragmented yet intellectually primed, religiously alive yet lacking a single moral center—that Mawlāy Idrīs arrived after surviving the massacre of Fakh. The Maghrib did not wait for him to become Muslim; it waited for him to become unified. The ethical legacy of Imām Zayd, the rational discourse of the Muʿtazila, the political maturity of the Awraba, the dynastic memory carried by Zanāta, and the Moroccan–Andalusian axis forged by centuries of shared history all converged to produce a singular moment of recognition. When the Awraba extended their bayʿa in 172/789, they did not pledge allegiance to a stranger but to the long-awaited moral axis capable of transforming competing experiments into a Western Imamate rooted in prophetic descent and attuned to the realities of the far West.

With Mawlāy Idrīs, the Maghrib ceased to be a landscape of parallel polities and became instead a single civilizational project, one that would define Moroccan identity for more than a millennium.

3. Mawlāy Idrīs I: The Western Imamate Begins

Mawlāy Idrīs did not enter the Maghrib al-Aqṣā (roughly modern Morocco and western Algeria) as a claimant negotiating his place among tribes; he entered it as a fact that reorganised the horizon of power. His presence did not ask whether authority was available in the Maghrib—it exposed that authority had been missing its rightful center since the Battle of al-Ashrāf severed the East from the West. The Umayyad sword had shattered on Moorish resistance, the Abbasid claim had never crossed the desert with conviction, and what remained across the Maghrib was force without legitimacy and doctrine without gravity. Into this landscape came a man whose lineage did not require explanation, whose silence carried more weight than proclamations, and whose very survival after Fakh announced that the prophetic household had not been extinguished but displaced. From the moment Mawlāy Idrīs stood in Walīli, the question was no longer whether Morocco could be ruled, but whether Baghdad and Cordoba could tolerate a rival center grounded in the blood of the Prophet ﷺ.

The claim Mawlāy Idrīs embodied was not local. It was not tribal. It was not improvisational. It was caliphal in scope, even when it avoided the vocabulary of empire. His khuṭba did not circulate as a pious sermon but as a declaration of moral sovereignty. His letters to the scholars of Egypt were not appeals for endorsement; they were notices that the West had entered the circle of legitimate command without Abbasid mediation. The Abbasids understood this immediately. They did not hear in his words a dissident voice but a rival grammar of rule—one that drew its authority directly from the House of the Prophet ﷺ and therefore rendered dynastic succession, court theology, and coerced consensus structurally obsolete. What Baghdad sensed was not rebellion but replacement.

Cordoba sensed it too. The second Umayyad state, often misread as an Andalusian miracle, was in truth a Moroccan creation from its first breath. ʿAbd al-Raḥmān al-Dākhil survived because Zanāta blood protected him, because Nakkūr sheltered him, because Berber arms escorted him across the strait and seated him in al-Andalus. The Umayyad restoration was Maghribi in muscle even as it draped itself in Syrian memory. Yet the Umayyads ruled by survival, not legitimacy. Their authority rested on endurance after catastrophe, not on prophetic inheritance. Mawlāy Idrīs therefore did not merely challenge Cordoba politically; he eclipsed it symbolically. Fez (Fās) did not need to outmatch Cordoba in splendor to threaten it. It threatened Cordoba by existing as a city whose ruler did not descend from conquerors but from the Messenger ﷺ himself.

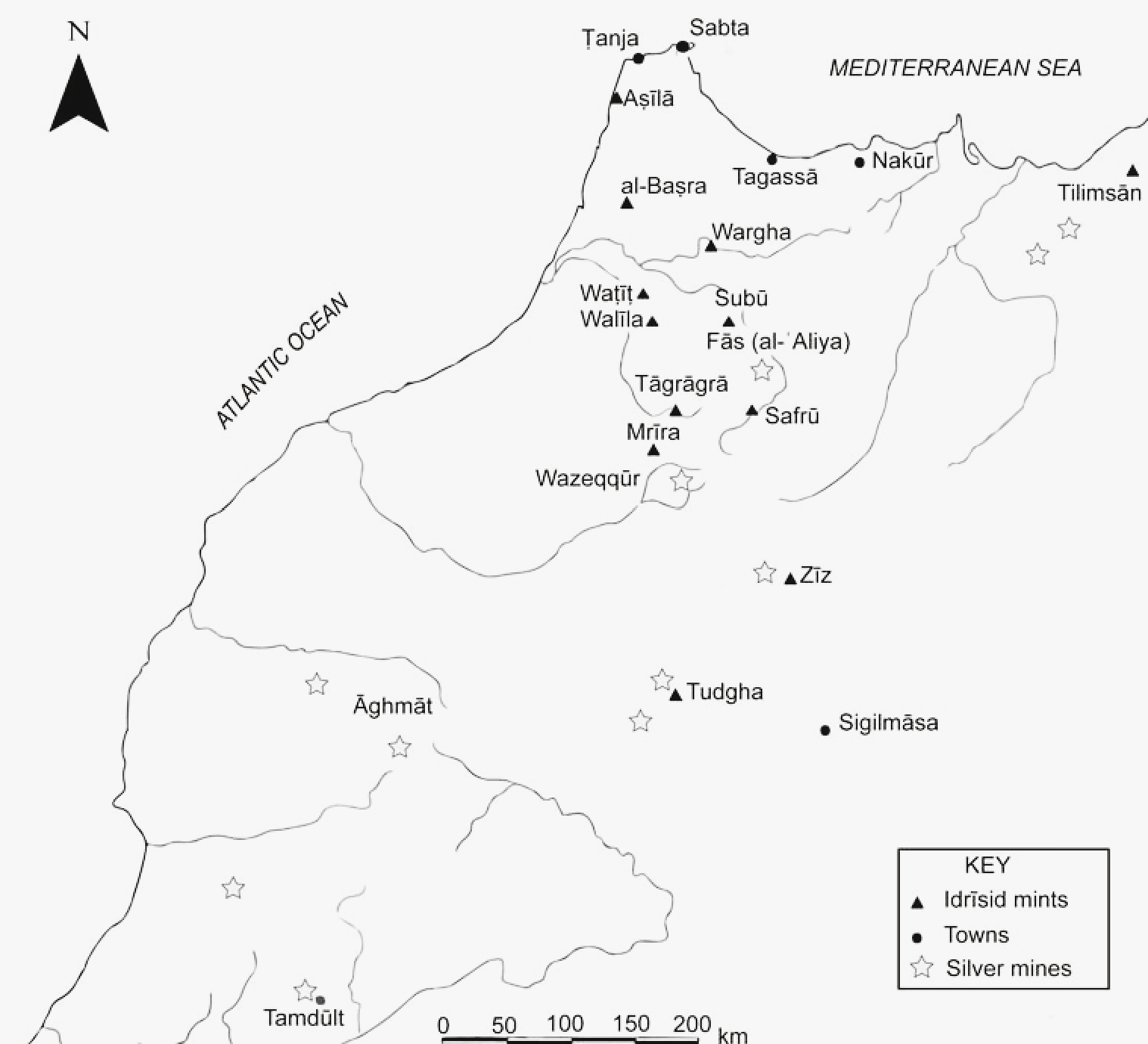

Morocco under the Idrīsids: Mints, Towns, and Silver Infrastructure (2nd–3rd c. AH / 8th–9th c. CE)

The choice of Fez was neither incidental nor aesthetic. Mawlāy Idrīs read the land with the eye of a statesman, not a mystic. He chose a site bound by rivers, fed by springs, protected by mountains, and open to trade routes that braided the Sahara, the Atlantic, and the Mediterranean into a single economic field. Wādī al-Jawāhir—the River of Gems—was not a poetic name; it was an inventory of power. Water meant mills, mills meant grain, grain meant silver, silver meant sovereignty. Thousands of wheels turned day and night, grinding wheat into currency long before coins bore inscriptions. Fez rose not as a palace city but as a hydraulic engine whose labor fed authority upward. This was not an imitation of Baghdad’s ceremonial excess nor Cordoba’s courtly refinement. It was something older and more dangerous: a city whose wealth was structural, not performative.

From this abundance emerged the Idrīsid dirham, and with it a declaration that Morocco had entered history as a monetary sovereign. Coinage is never neutral. To mint is to rule, and to circulate is to convince. Mawlay Idrīs struck silver dirhams and copper fulūs immediately upon his proclamation as imām in 172/788–789, a practice continued by his successors, signaling that authority in the Maghrib would be articulated not only through bayʿa and khuṭba (the sovereign prerogative by which a ruler’s name is proclaimed during the Friday congregational sermon), but through metal, weight, and inscription.

The early Idrīsid dirhams largely followed Abbasid numismatic conventions, yet their distinctions were deliberate and principled. Beneath the name of Idrīs appeared the name of ʿAlī, affirming lineage to the Household of the Prophet ﷺ within the medium of currency itself. More decisively, the coinage replaced the prevailing Abbasid formula with the Qurʾānic proclamation of truth, Qurʾān 17:81 (“The truth has come, and falsehood has perished”), explicitly attributed to Mawlay Idrīs. This verse bore a known association with the cause of Ahl al-Bayt, having appeared earlier on coinage issued during the uprisings of al-Nafs al-Zakiyya in Medina, Ibrāhīm in Baṣra, and Yaḥyā in Ṭabaristān. Struck in Fez, its reappearance signaled the establishment of authority grounded in truth and justice, and situated the Idrīsid mint within a continuous Hasanid tradition while standing apart from Abbasid command.

The Idrīsid dirham thus did not merely facilitate exchange; it carried allegiance. Its inscriptions announced wilāya as much as weight. In a world where the Abbasids had weaponized sovereign theologization and the Umayyads authoritarian solidarism, the Idrīsids fused economy and Prophetic wilāya into a single act of governance. Silver from the mountains, and grain from the plains passed through Fez and returned stamped with an authority that did not require Baghdad’s blessing.

Markets followed. So did people. Fez became a magnet for those fleeing the violence of collapsing orders: Andalusi families escaping Umayyad purges, scholars displaced by Abbasid suspicion, merchants seeking stability beyond Khārijite volatility. Refuge did not weaken the city; it multiplied it. New quarters formed, trades specialized, alliances crystallized. Zawāgha, the indigenous population, did not vanish; they anchored the city’s continuity. Arab tribes did not erase Amazigh structures; they fused with them. What emerged was not a transplanted society but a Fāsi one—disciplined by law, energized by trade, and bound by allegiance to an imamate that felt neither foreign nor imposed.

This allegiance was enacted weekly. Mawlāy Idrīs understood the mosque as an instrument of state. Masjid al-Ashyākh was not merely a place of prayer; it was Morocco’s first parliament, court, and broadcasting tower. From its minbar flowed the khuṭba that named authority, articulated policy, and reminded the population that justice was not abstract but administered. Here disputes were resolved, oaths sworn, commands issued. The mosque replaced the palace because the imamate did not require theatrical separation from the governed. Authority resided where the community gathered, not behind walls.

Silver dirham issued under Idrīs I, struck at Tudgha in 174/792, modeled on Abbasid coinage but uniquely inscribed with the name ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib, asserting Idrīsī sharīfian legitimacy through lineage and coinage.

From Fez, Mawlāy Idrīs moved outward with deliberate speed. Aghmāt was secured to anchor the south. Barghawāṭa, whose heterodoxy threatened the Qurʾanic order itself, was weakened and contained, not glorified as an exotic anomaly. Sigilmāsa, guardian of the Saharan gold routes, was brought into the Idrīsid orbit, tying the economy of West Africa to the sovereignty of Fez. Each campaign followed the same pattern: force when necessary, incorporation when possible, reorganization always. Territories were not looted; they were integrated. Resistance did not invite annihilation; it invited restructuring.

Throughout this expansion, Mawlāy Idrīs did not impose Mālikism, nor did he seek to reconcile his project with Abbasid jurisprudence. The ethical core of his rule remained Zaydī–Hasanid: justice as obligation, resistance to tyranny as duty, wilāya as axis. Mālikism would later enter al-Andalus as a political tool after Umayyad legitimacy eroded, but in Mawlāy Idrīs’s Morocco it held no founding role. To suggest otherwise is to mistake later apologetics for original intent. Tolerance is not adoption, and accommodation is not allegiance.

The ideological geography of the West shifted accordingly. Tanga (Tangier) emerged as a Shiʿi hub, as Abū al-Ḥasan al-Ashʿarī (d. 324/935) himself observed in Maqālāt al-Islāmiyyīn—not because Morocco had become doctrinally sectarian, but because wilāya had found land. Fez functioned as a new Kūfa, not in imitation but in structure: a city where allegiance, politics, and theology converged in lived space. khuṭbas were not sermons but mobilizations. Coins were not metal but messages. Marriage itself became policy when Mawlāy Idrīs wed Kanza, binding the imamate to Amazigh power and ensuring that succession would not fracture along tribal lines. The state acquired heredity without forfeiting legitimacy.

Baghdad watched all of this with mounting alarm. What frightened the Abbasids was not Mawlāy Idrīs’s rhetoric but his success. The West was no longer a distant frontier; it was becoming a rival center with its own economy, army, ideology, and prophetic claim. The path toward Ifriqiya lay open. Beyond it, Egypt. The logic was unbearable. Thus poison replaced debate, and infiltration replaced confrontation. The betrayal of al-Shammākh, a Zaydī who sold principle for proximity, was not an anomaly but a method perfected by the Abbasids against Ahl al-Bayt. Mawlāy Idrīs was murdered not because he failed, but because he was about to succeed too completely.

Yet the assassination misfired. The state did not collapse. Rāshid held administration steady. Tribes did not scatter; they consolidated. Most tellingly, the unborn child in Kanza’s womb was acknowledged as ruler before drawing breath. A crown placed on a pregnant woman is not symbolism; it is constitutional clarity. It declared that the Idrīsid project was no longer charismatic but institutional, no longer contingent on a single life but embedded in Morocco itself.

By the time Mawlāy Idrīs was buried in Walīli (modern Zarhūn), Morocco was no longer a periphery awaiting direction. It was a center that had learned to govern itself with prophetic legitimacy, economic intelligence, and territorial command. Fez stood not as an experiment but as a challenge—to Baghdad’s theology, to Cordoba’s dynasty, and to history’s assumption that the West merely receives what the East produces. What Mawlāy Idrīs founded was not a dynasty alone, but a new axis of Islam, anchored in baraka, sustained by labor, defended by geography, and announced to the world in silver.

4. Mawlāy Idrīs II: The Imām Who Never Saw the East

“Do not bow to any authority but ours, for the Kingdom of God (imāmat al-Ḥaqq) you seek is not attainable—except through us.” This was not a slogan uttered in defiance. It was a declaration of existence. When Mawlāy Idrīs II would later pronounce these words in his first khuṭba in 188/804, they did not echo rebellion — they announced arrival. The far West was no longer waiting for recognition; it spoke as origin. What rendered this declaration intolerable to Baghdad and its Aghlabid vassals in Ifrīqiya, as well as to the Umayyad emirate across the straits in al-Andalus, was not its audacity but its timing: it was uttered by an imām who had never seen the East, owed it nothing, and embodied a form of legitimacy that lay beyond negotiation or containment.

That legitimacy began before his birth. When Mawlāy Idrīs I was assassinated by Abbasid poison in 177/793, the Idrīsid state did not collapse into panic. It froze. Morocco held its breath. The tribes did not scatter. The bayʿa was not revoked. Authority did not revert to confederations. Instead, the land waited — not metaphorically, but politically — for what lay in the womb of Kanza bint Ishāq.

For two months, Morocco existed in suspension. Was the child a boy or a girl? Was the lineage to continue, or was the Idrīsid project to be remembered as a brief flare extinguished before maturity? This was not private curiosity; it was a matter of state. Amazigh leaders, elders of Awraba, Sanhāja, Hawwāra, and Zanāta, watched the pregnancy as one watches a frontier battle. The fate of a sovereign Islamic order hinged on birth.

When the child was born male, the reaction was immediate and decisive. This was not merely relief — it was recognition. The tribes did not say “a son has been born.” They said: Idris has returned. They named him Idris. Not as memory. As continuity. Calling him Idris was not sentimental homage to a murdered father. It was a political act. It declared that the imamate had not been interrupted, only concealed. That assassination had failed. That Abbasid poison had not broken the chain. The name Idris became a statement: legitimacy survives death.

“Do not bow to any authority but ours, for the Kingdom of God (imāmat al-Ḥaqq) you seek is not attainable—except through us.”

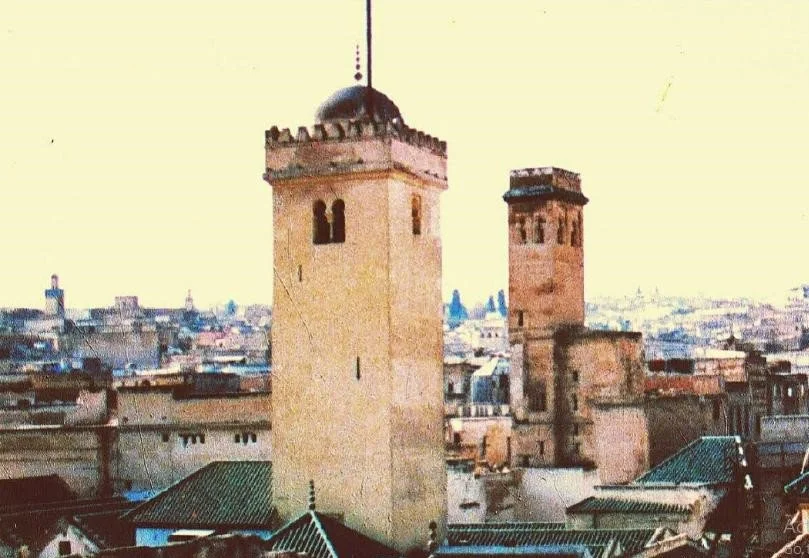

The image shows the tomb of Mawlay Idrīs II in Fez, centered on a richly adorned catafalque draped in golden silk, embroidered with Qurʾanic calligraphy. The cloth glows softly under filtered light, emphasizing reverence rather than excess. Above it rises the green dome, a symbol of lineage and sanctity, enclosing the space with calm authority. The surrounding architecture is restrained and solemn, guiding the eye toward the tomb as the spiritual focus. The atmosphere conveys silence, gravity, and devotion, marking the shrine as the most revered burial sites in North Africa.

Around the infant formed a triangle of guardianship that would shape the most Moroccan imām in Islamic history.

Kanza, his mother, was not a passive vessel of lineage. She was Amazigh nobility, Idrīsid by marriage, Awraba by blood, and Moroccan by instinct. Through her, the child belonged not only to the Prophet’s House but to the land itself. Her pregnancy was guarded as a trust. Her son was raised not as a foreign prince but as the child of the tribes. In her care, the imamate learned intimacy.

Isḥāq (d. 192/808), his grandfather, was not merely a political elder. He represented the continuity of Amazigh authority that had chosen Idrīs I not out of fear but out of expectation. His presence ensured that the state did not drift back into tribal fragmentation during the child’s minority. He was the anchor of experience, the guarantor that governance would not be suspended while lineage matured.

And then there was Rāshid (fl. 188/804). He was not a regent in the classical sense, but the memory of the father walking beside the son. He carried the political intelligence of Mawlay Idrīs I—the grammar of alliances, the discernment of enemies, the cartography of loyalties—and transmitted it without suspending the labor of rule. He raised the child not as a sheltered heir, but as an imām to be forged, even as the state continued to extend its reach under his hand. Education was relentless: Qurʾān before play, language before leisure, history before ornament. Horsemanship, archery, and strategy were taught not as aristocratic pursuits, but as instruments of survival, imparted alongside an active governance that did not preclude, and indeed quietly prepared for, expansion beyond Morocco toward Ifrīqiya.

By the age of seven, the child had memorised the Qurʾān. By eleven, he had absorbed not only law and language, but the psychology of power. He knew who had betrayed his father. He knew which tribes hesitated. He knew why Baghdad feared Morocco. Nothing was hidden from him. When the bayʿa was finally taken for Mawlāy Idrīs II in the mosque of Zarhūn, it was not a symbolic oath to a boy. It was a renewal of a decision already made years earlier: Morocco would not return to the East.

From that moment, the Idrīsid project stopped breathing quietly and began to speak aloud. If Mawlay Idrīs I ruled with restraint and geometry, his son ruled with sound—with a voice meant to travel, collide, and refuse containment. This was not noise as chaos, but noise as sovereign disturbance. Mawlay Idrīs II did not limit himself to pious letters of daʿwa dispatched toward Egypt or the Ḥijāz; he practiced diplomacy as proclamation. Envoys moved. Titles circulated. Names were spoken where they were not supposed to be heard.

The khuṭba became his instrument. Not a sermon, but a weekly act of domination. Each Friday, his name rose from pulpits as a reminder that the assassination had failed twice—first in poison, then in attempted oblivion. He claimed Amīr al-Muʾminīn, the title still borne by the Moroccan monarch, not as ornament but as acoustics: a name designed to echo across seas and chancelleries.

And it did. In 198/813, Pope Leo III informed Charlemagne that the patrician Gregory of Sicily had received a Muslim envoy sent by the amiralmumin of Africa—a mangled Latin ear catching what Baghdad feared most: the West speaking in the first person. This was not rumor; it was recognition forced by presence.

Even the coinage shouted. At Tahlīṭ, in 197/812–813, a singular coin was struck declaring: “Muḥammad is the Messenger of God and the Mahdī is Idrīs b. Idrīs.” Not merely a ruler, but al-Mahdī—a name loaded, dangerous, and deliberate, inherited from the vocabulary of the Ahl al-Bayt and the blood of al-Nafs al-Zakiyya. Metal, sermon, embassy: three registers of the same voice.

This was the signal Baghdad could not suppress: a western polity that did not wait for formal recognition but embedded itself directly into the monetary circuits of the age. Idrīsid dirhams entered exchange networks spanning the Carolingian world, the Scandinavian trading sphere, and the Byzantine Mediterranean, before circulating in greater density through the Khazar Khaganate and other steppe polities, and more centrally within Abbasid accumulation zones across the eastern caliphate.

Yet silver was only the visible layer. Ibn al-Abbār reports in al-Ḥulla that Mawlay Idrīs II minted gold dīnār—a direct challenge to caliphal monopoly, for gold coinage was restricted to the great powers: Byzantium and Baghdad alone. The Aghlabid governor Ziyādat Allāh (223/838) sent al-Maʾmūn al-ʿAbbāsī a sum of 1,000 dīnār struck in the name of Idrīs al-Ḥasanī—not as tribute but as evidence. The message was clear: a descendant of the Prophet ﷺ was minting gold independently in the far West. This was not a provincial emirate. It was a rival caliphate.

This imām had no memory of Mecca or Medina, yet he carried them in lineage. He had never seen the East, yet the East trembled at his name. He was not a refugee; he was a native sovereign. Not a survivor; a beginning. Morocco did not merely accept him. It embraced him as its own creation.

This is why Mawlāy Idrīs II feels closer than his father. Why his tomb is warmer in the popular imagination. Why Fez carries his imprint more deeply. He was not the man who arrived — he was the man who grew. And with him, Morocco stopped being a destination for legitimacy and became its source.

5. The Two Cities, The Two Imams

Between 172 and 176 (788–793), Mawlay Idrīs I carved Fez into existence on the right bank of Wādī al-Jawāhir. He negotiated with the Banū Yazghitān, purchased their forested land, laid foundations, raised walls, built Masjid al-Ashyākh, and struck the first Idrīsid dirhams. He did this while consolidating tribal alliances, expanding eastward toward Tlemcen, and fending off Aghlabid hostility from Ifrīqiya. Fez was not leisurely conceived—it was built under pressure, by a Hachimite imām who understood that survival required more than bayʿa and baraka. It required place: a city that could mint coins, grind grain, house armies, and anchor loyalty when words alone failed. Then in 177/793, Abbasid poison ended him.

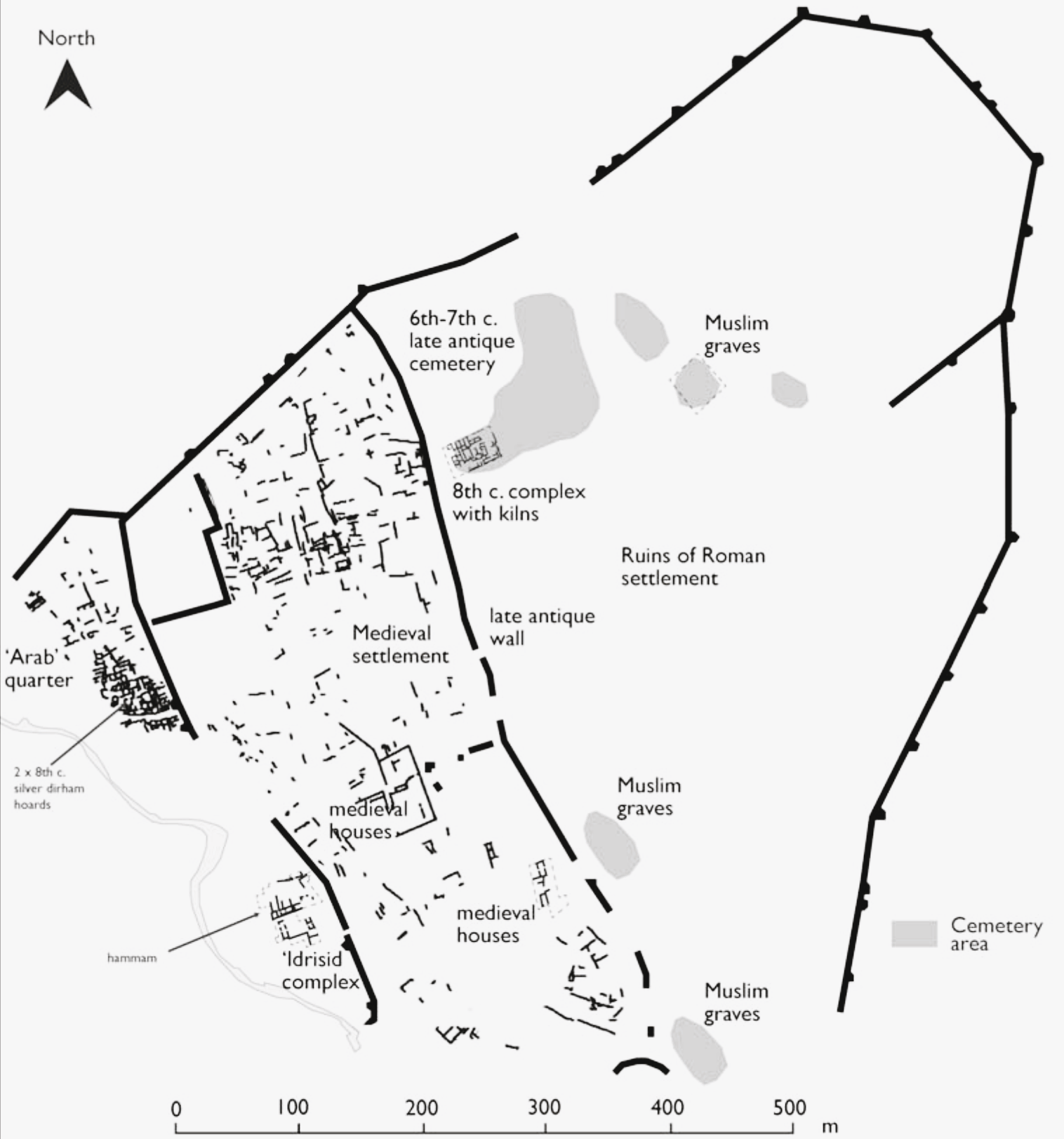

Idrīsī Palace

Plan of early medieval Volubilis, highlighting the location of the Idrīsī palace complex, after Corisande Fenwick and the INSAP–UCL Volubilis Archaeological Project, emphasizing the spatial anchoring of Idrīsī authority within the former Moorih city.

For sixteen years, Fez stood as his monument and his widow's trust. Kanza bint Ishāq carried the state in her womb, then in her arms, then in her counsel as Rāshid trained the boy who bore his father's name but had never seen his father's face. Idrīs II grew up inside the architecture his father had left behind—walked the streets his father had planned, prayed in the mosque his father had built, watched the river turn the wheels his father had set in motion. He learned statecraft not from theory but from inheritance made visible. Every wall in Fez was a lesson. Every mill was a command.

By 188/803, when the bayʿa was formally renewed for him in the mosque of Zarhūn, Mawlay Idrīs II was no longer a boy. He was eleven, but eleven in a world where survival required precocity, where assassination was policy, and where hesitation invited predators. By the time Rāshid himself was assassinated—another Abbasid agent, another mawlā bought with promises—Idrīs II was alone, but he was ready. Four years later, in Rabīʿ al-Awwal 192 (January 808), he crossed the river his father had named Wādī al-Jawāhir and began building on the opposite bank. This was not expansion. It was declaration.

Fez, built by Idrīs I, was the city of arrival. It announced that the West could shelter a sharīf, that prophetic lineage could take root outside the Hijaz, that an imamate did not require Abbasid permission to exist. It was defiant in its existence but cautious in its ambition. Idrīs I built walls thick enough to withstand siege, a mosque large enough to gather the faithful, a mint capable of striking currency, and a network of mills to convert water into bread. He built what a refugee builds when he knows enemies are watching: a city designed to survive.

Al-ʿĀliyya, built by Idrīs II in 192, was the city of ascendancy. It announced that survival was no longer the question—sovereignty was. The name itself—al-ʿĀliyya, "the Most High"—was not topography alone (though the western bank did rise slightly above the eastern). It was theology compressed into syllables. It echoed ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib, gate of prophetic knowledge and ancestor of the line. It proclaimed elevation—moral, spiritual, political. Where Fez had asked "Can we endure?", al-ʿĀliyya answered "We have already won."

The duality was architectural and constitutional. Two cities facing each other across a river, each with its own walls, gates, mosque, qaysariyya, mint, and markets. But they were not twins—they were stages. Fez was the foundation laid by a father who had fled Fakh with wounds still fresh, who remembered the taste of Abbasid betrayal, who built knowing that survival was negotiation with geography, tribes, and time. Al-ʿĀliyya was the elevation built by a son who had never seen the East, who owed it nothing, who inherited his father's caution but refused his father's limits. This is the difference: Idrīs I built to anchor. Idrīs II built to announce.

When Mawlay Idrīs II purchased the land of the Banū al-Khayr al-Zuwāghiyyūn for 3,500 dirhams—a thousand more than his father had paid for the eastern bank—he was not merely acquiring real estate. He was relocating sovereignty. He did not add to Fez; he built beside it, above it, in answer to it. He established his residence at Dār al-Qayṭūn, a name that would remain tied to Idrīsid memory for centuries. Adjacent to it, he built Masjid al-Shurafāʾ—the Mosque of the Sharifs—where he would lead prayers, deliver khuṭbas, administer justice, and eventually be buried.

This mosque was bigger than Masjid al-Ashyākh across the river. It was more central to the commercial traffic of the city, and it carried something his father's mosque could not: presence. It was the place where the living imām governed, not the place where a martyred father was remembered. It was the site where allegiance was renewed weekly, where law was announced, where the baraka of the Ahl al-Bayt was not a historical claim but a fact, visible, tangible, seated on a minbar and speaking in a voice the gathered could hear.

From the height of al-ʿĀliyya, Idrīs II could see both cities: his father's Fez to the east, his own creation to the west, and between them the river threading both into a single economic organism. What began as a few installations along the water soon expanded; by the early 3rd/9th century, numerous workshops operated on its banks, and in later periods the number grew dramatically. The steady flow powered mechanisms that processed grain and sustained urban growth. As inhabitants multiplied, fiscal revenues increased, enabling military organisation and, eventually, the consolidation of territorial authority. This was the infrastructural vision set in motion by Idrīs I and systematically developed by his son. Together, the paired settlements evolved into an integrated economic system driven by the river’s regulated energy.

The chroniclers debated endlessly the origin of the name "Fez." Some said it came from faʾs, the great golden axe discovered when digging foundations—so large it seemed mythic, a tool from an earlier age when giants worked stone. Others said it inverted Sāf, an ancient name whispered by a Christian monk who saw Idrīs I surveying the land and foretold a city that would outlive empires. Others still claimed it honored a Persian contingent killed in a landslide during construction, or a stuttering man who dropped the rāʾ from Fāris and gave the city its name by accident.

The variety of explanations is itself the answer. "Fez" became a name that absorbed every origin story because the city absorbed every population. But beneath the legends, the meaning was never obscure. Faʾs is the blade—the tool that cuts earth, that splits stone, that makes wilderness into field. It is the instrument of transformation, the force that turns nature into order. To name a city "Fez" was to name it conquest over landscape, to declare that this place would not remain forest and spring but would become polis, shaped by human will and prophetic purpose.

And "al-ʿĀliyya"—the Most High—was the hand that raised the blade.

Together, the two names formed a single statement: Fez cuts, al-ʿĀliyya commands. One was force applied to earth; the other was authority applied to history. One was the labor of the father; the other was the voice of the son.

What unfolds after the founding of al-ʿĀliyya is not urban expansion but the strategic ignition of a metropolis destined to shoulder a sacred and enduring mandate—precisely what al-Qayrawān in Ifrīqiya, for all its administrative stature, never achieved. Under the Umayyads and later the Abbasids through their Aghlabid governors from Khurasan, al-Qayrawān served as a fortified checkpoint, a station for imperial oversight rather than a holy capital with its own radiating authority. Its purpose was surveillance, not sanctification; order, not destiny.

This is why Fez rapidly ceases to resemble earlier Maghribi centres. It does not imitate Córdoba, a courtly city revolving around a single palace axis. Nor does it replicate Baghdad, a caliphal projection sustained by distant imperial extraction. Fez emerges instead as a polycentric organism structured around movement rather than monument. Its force resides everywhere and nowhere at once: dispersed through mosque and market, mint and mill, yet ultimately manifesting as holiness, baraka, and the unmistakable stamp of divine success.This diffusion is not dilution. It is the architecture of endurance—the reason Fez persists where other capitals remained stations on someone else’s road.

By the time al-ʿĀliyya is complete, Fez—in the expanded sense, meaning both banks together—possesses a doubled urban infrastructure designed for resilience: two congregational mosques (Masjid al-Ashyākh built by Idrīs I, and Masjid al-Shurafāʾ built by Idrīs II), two qaysariyyas for high-value trade in silks, books, and spices, and two mints, each bank capable of striking dirhams independently. Markets are organized by craft, with blacksmiths, tanners, dyers, carpenters, potters, and weavers each claiming their own street, standards, and autonomy. Each bank has its own walls and gates, rendering it defensible on its own, while hydraulic infrastructure—springs, watercourses, mills, and irrigation channels—feeds both sides of the river, binding the twin cities into a single economic organism while preserving their structural independence.

This was not duplication born of inefficiency. It was redundancy born of foresight. If one bank burned, the other survived. If one mosque closed, the other taught. If one mint was sacked, the other coined. There was no single point of failure. You could not behead Fez because Fez had no single head.

Compare this to Baghdad, built by the Abbasid caliph al-Manṣūr in 145–149 (762–766) as a perfect mandala—concentric circles radiating from the caliph's palace at the center, streets aligned like spokes, gates positioned at cardinal points, a geometric diagram of hierarchy frozen into brick and earth. It was breathtaking. It was also structurally fragile. When the Mongols sacked Baghdad in 656/1258, they destroyed the center, and the city ceased to function. The organizing principle was the palace; remove it, and the streets lost their meaning.

Compare it to Córdoba, where the Great Mosque, the Umayyad palace complex, and the administrative quarters all orbited caliphal presence. The city's economy depended on Andalusi agricultural surplus and Mediterranean trade networks organized by state contract. When the Umayyad caliphate collapsed in 422/1031, the organizing principle vanished. Within a generation, Córdoba fragmented into irrelevance, its population scattered to the taifa kingdoms, its mosques emptied, its markets reduced.

Fez had no center to strike at. Authority circulated through its fabric like lifeblood. The imām held significance, yet the imām did not constitute the system. The system was hydraulic, architectural, devotional, economic—and sanctified by baraka, framed by prophecy, sustained by allegiance. Such a structure could endure the removal of any single piece, even the ruling house that inaugurated it.

This is why when Mawlay Idrīs II was assassinated in 213/828—another Abbasid poisoning, another mawlā bought with promises, another son of the Prophet ﷺ dead before his time—Fez did not collapse.

But water and walls alone do not explain what Fez became. What transformed two settlements into a metropolitan center—what made Fez dangerous to Baghdad and Córdoba alike—was not infrastructure but human magnetism. People came because Fez offered what no other Maghribi city could: refuge that felt like opportunity.

The first wave arrived in 189/804, just before al-ʿĀliyya was founded—an Andalusi delegation whose presence would alter the trajectory of Fez. They were not mere exiles drifting westward in search of shelter. They were survivors of the Rabaḍ uprising, the great convulsion that had shaken Córdoba under al-Ḥakam I: scholars, qāḍīs, administrators, artisans, and Jewish financiers preserving commercial networks, whose revolt had exposed the fracture between moral authority and princely rule. Emerging from the arbaḍ—the suburban quarters that sustained Córdoba’s economic, intellectual, and commercial life—they brought with them a political theology shaped by resistance and a model of urban cohesion grounded in shared craft, law, and commerce.

Mawlay Idrīs II did not merely shelter them—he employed them in the key pillars of his state. He appointed ʿUmayr ibn Muṣʿab al-Azdī as vizier, entrusted the judiciary to ʿĀmir ibn Muḥammad ibn Saʿīd al-Qaysī, and appointed Abū al-Ḥasan ʿAbd al-Malik ibn Mālik al-Mālikī al-Anṣārī as secretary. They became his scribes, his tax collectors, his diplomats, his urban planners. They brought institutional memory from al-Andalus—how courts functioned, how markets were regulated, how mosques were endowed, how cities worked—and embedded that knowledge into the nascent Idrīsid administration.

Then came the second wave in 202/817: the exiles of al-Rabaḍ, the suburb of Córdoba that had revolted against Umayyad taxation and been crushed with systematic brutality. The Umayyad response was not negotiation but expulsion. Some eight thousand families—men, women, children, entire kinship networks—were driven out, their properties confiscated, their futures erased. They scattered across the Mediterranean: some to Alexandria, where they became mercenaries; some to Crete, where they founded an emirate; and some—perhaps three thousand families—came to Fez.

Mawlāy Idrīs II did not disperse the Andalusi exiles among tribes or bury them in rural settlements. He gave them a quarter—visible, central, and named after them. The eastern bank, once simply Fez, became ʿAdwat al-Andalus, the Andalusian Bank. And to anchor their presence within the city’s ritual and political architecture, the state built for them a new congregational mosque, Masjid al-Andalus, ensuring that their quarter possessed a civic heart equal in stature to any Idrīsid foundation. This was not charity. It was strategy. Every family settled there, every workshop opened, every prayer offered beneath the arches of the new mosque amounted to a diplomatic rebuke to Córdoba: a public testament that the Umayyads had lost the loyalty of their own subjects, that their justice rang hollow, and that their authority could, in fact, be refused.

And these Andalusis brought more than bodies. They brought civilization—not as metaphor but as measurable technique. They were masters of carpentry (the geometric precision of Andalusi woodwork, the interlocking joints that required no nails), ironwork (forges, tools, weapons), construction (the art of building with rammed earth, tile, and stone in ways that withstood earthquake and siege), and above all the decorative arts: zellij (mosaic tilework, tiny glazed pieces arranged in patterns that seemed to breathe), plaster carving (muqarnas, arabesques, calligraphy cut into walls), and architectural ornamentation that transformed surfaces into scripture.

Fāsī architecture—the style that would define Moroccan visual culture for a millennium, the aesthetic that tourists now photograph in medinas without knowing its origin—was born in this moment. It was Andalusi technique applied to Amazigh structure, shaped by Idrīsid ambition and Moroccan materials (limestone from the Middle Atlas, cedar from the Rif, clay from the Saïss plain). It was a fusion that could only happen in Fez, where migration was not trauma but catalysis.

They were not the last to arrive. Over the same decade, families from Ifrīqiya—especially from al-Qayrawān—began moving into Fez, driven by Aghlabid volatility or drawn by a city whose prestige in scholarship and commerce was rising with unusual speed. They settled on the western bank, in al-ʿĀliyya, which soon became known as ʿAdwat al-Qarawiyyīn, the Qayrawani Bank. To root this community within the emerging metropolitan structure, the Idrīsids established a second congregational mosque, Masjid al-Qarawiyyīn, giving al-ʿĀliyya the same architectural and institutional weight as the Andalusi bank across the river.

Decades after Mawlāy Idrīs II’s death, al-Qarawiyyīn—built in the shadow of his sanctuary and within sight of his tomb—had become the most consequential institution in the western Islamic world. Its location was not incidental. To pray, teach, or issue judgment in al-Qarawiyyīn was to operate within the orbit of the Idrīsid legacy; the mosque’s authority was inseparable from the saint-founder whose memory anchored the city. Even when dynasties shifted, the proximity of the mosque to Mawlāy Idrīs’s shrine ensured that political legitimacy in Fez passed through sacred, Idrīsid geography.

From this vantage point, al-Qarawiyyīn evolved into the intellectual parliament of the Muslim West. Here Mālikī law was interpreted for the entire Maghrib and al-Andalus. Here scholars were examined and licensed, their ijāzāt recognized from Timbuktu to Cairo to Damascus. Here manuscripts were copied, authenticated, and circulated; the sanad of a ḥadīth or legal opinion gained weight simply by tracing a link to al-Qarawiyyīn. And here fatwās were deliberated that could stabilize rulers or isolate them, justify revolts or forbid them. It became the chamber where knowledge was certified, where consensus was shaped, and where power was debated before it was enacted.

Crucially, after the fall of the Idrīsid state, it was al-Qarawiyyīn—and the scholars who governed its intellectual life—that ensured Mālikism became the primary madhhab of Morocco. Without a central dynasty to impose doctrine, the authority of law migrated to the mosque. Judges, jurists, and notables all passed through its curriculum; the Mālikī school became the shared legal language of cities, tribes, and courts alike. What began as a congregational mosque for a Qayrawani quarter thus became the anchor of Moroccan orthodoxy and the enduring heir of Idrīsid political theology.

This was the genius of Fez's cosmopolitanism: it did not erase difference but institutionalized it. Andalusis brought craft, Qayrawanis brought scholarship, Awraba and Zanāta brought military power and tribal networks, trans-Saharan merchants brought gold, Jewish craftsmen brought metallurgy and specialized finance, Christian traders (in the early decades) brought Mediterranean connections and the languages of commerce. No single group could claim monopoly. No single identity could define the city. Fez became pluralist by structure, and this pluralism made it anti-fragile.

When one patronal class weakened, others sustained the city. When one dynasty fell, Fez’s networks endured. This resilience explains its survival through successive ruptures: the fragmentation of the Idrīsid state after (213/829), the Almoravid conquest in the 5th/11th century, the Almohad invasion in the 6th/12th century, the Marinid decline in the 9th/15th century, the Saʿdian interregnum in the 10th/16th century, and the ʿAlawite consolidation in the 11th/17th century. The city did not depend on any single ruler—it depended on the cumulative strength of its systems.

6. Strategic Dispersal, the Civil War, and Resilience

When Mawlāy Idrīs II died in 213/828—poisoned, like his father before him, by an agent in Abbasid pay—he left behind not a stable succession but a constellation of grief. His mother, Kanza bint Isḥāq, had already buried three generations: her father Isḥāq, the Awraba chieftain who had first welcomed Idrīs I to Walīlī; her husband, the founding imam; and now her only son, dead at thirty-seven. None had perished from illness or old age. All had been murdered—methodically, deliberately, by a caliphal apparatus in Baghdad that understood one thing with absolute clarity: the Idrīsids could not be allowed to endure.

Yet endure they did, and Kanza understood why. She was not merely the widow of one imām and the mother of another. She was the matriarch of the most dangerous lineage in the Islamic West—twelve grandsons, all young, all bearing the blood of the Prophet ﷺ, and all visible targets for the same poison that had taken their father and grandfather. The eldest, al-Qāsim, was perhaps twenty-one. Muḥammad (221/836), known as al-Khalifa (the Viceregent), the second-born, perhaps twenty. ʿĪsā (233/847), known as al-Anwar (the Radiant), the third and most powerful, a few years younger still. Some were barely adolescents. At least one may still have been a child.

Kanza had watched the Abbasids perfect their method. They did not invade. They did not declare war. They infiltrated. A servant bought with promises. A mawlā positioned near the imām's table. A trusted figure turned informant. Rāshid, the loyal guardian who had raised Idrīs II and administered the state during his minority, had been killed the same way. The pattern was undeniable: concentration invited assassination. So long as the Idrīsids gathered in a single city, under a single roof, around a single table, they remained within reach of an intelligence network that had already demonstrated, across three generations, that it could kill anyone, anywhere, at any time.

Kanza's response was not panic. It was geometry. She divided Morocco. Not in the way later historians would frame it—as the tragic mistake of a grieving matriarch or the chaotic dissolution of a once-unified state—but as a calculated act of survival, executed with the precision of a general distributing forces across a battlefield. Each grandson was assigned a region. Each region corresponded to a strategic necessity. Each assignment reflected not merely his age or capability but the political and kinship networks that could protect him through his mother's lineage.

Al-Qāsim, the eldest, was given Tanga and the northern coast—Sala, the Rif corridor, and control over the Strait of Gibraltar. This was not a consolation prize. It was dominion over Morocco's most strategically vital threshold, the maritime gateway between continents, the passage through which armies, embassies, and ideas moved between the Maghrib and al-Andalus. To rule Tanga was to hold a blade to the throat of anyone who wished to cross.

Muḥammad, the second-born, was given Fez—the symbolic and economic heart of the Idrīsid project, the city his grandfather had founded and his father had doubled, the place where baraka, commerce, and legitimacy intersected most visibly. With Fez came nominal leadership over his brothers, a claim rooted in his position as second-eldest and his control over the city that bore the dynasty's imprint most indelibly. Yet nominal authority, as events would soon demonstrate, is a fragile thing when divorced from material power.

ʿĪsā, the third-born, was given the interior: Tadla, Tāmasnā, Sala, extending as far as Zagora. More importantly, he was given proximity to Jabal ʿAwwām, the silver mines that fed the Idrīsid dirham. ʿĪsā al-Anwar was not merely assigned a territory—he was granted control over the mineral foundation of sovereignty itself. In a state whose economy ran on silver, whose legitimacy was announced through coinage, and whose independence was measured by its ability to mint without external permission, ʿĪsā's domains were not peripheral. They were essential. And Īsā al-Anwar himself, even at his young age, was known to be charismatic, forceful, and capable—a prince whose personality matched the weight of his inheritance.

Dāwūd was placed at Hawwāra in the region of Wahrān, the eastern corridor connecting Morocco to Ifrīqiya. This was not exile—it was the assignment of a sentinel, a prince positioned where ʿAbbāsid and Aghlabid influence would have to pass if they wished to reach Fez. Ḥamza was sent to Zarhūn, where Idrīs I had first been proclaimed imām, a location thick with memory and legitimacy. ʿAbd Allāh was assigned Lamṭa—deep in the south, securing the edges of the Saharan trade routes and maintaining Idrīsid presence among the Ṣanhāja tribes of the pre-Sahara. ʿUmar, vigorous and loyal, was entrusted with the Rif highlands and the confederation of Sanhāja and Ghumāra tribes, a role that combined military command with diplomatic necessity.

And beyond these direct sons of Idrīs II, even the Sulaymanid line—the descendants of Sulaymān, brother of Idrīs I—retained Tlemcen, affirming that legitimacy was not monopolized by a single branch but distributed across the family.

This was not fragmentation. It was federation. And it was, in its essence, a replication of the Fez model across the entire territorial expanse of Morocco. Just as ’Mawlay Idrīs I had built Fez on one bank of Wādī al-Jawāhir and Mawlay Idrīs II had built al-ʿĀliyya on the other, creating a doubled city where neither half could collapse without the other surviving, so too did Kanza construct a doubled—indeed, a multiplied—state, where the fall of one node could not bring down the network.

Each grandson carried baraka. Each would marry into the tribes of his region, weaving Qurayshī blood into Amazigh kinship structures and creating a matrix of loyalty that transcended any single center. Each would build: mosques, markets, ḥammāms, mints if necessary, and in some cases entirely new cities. The Idrīsid presence was not to be confined to Fez. It was to be inscribed across Morocco's geography, written into its rivers, mountains, and coasts, so that even if Fez fell, even if one brother was killed, even if the Abbasids succeeded in poisoning another generation, the project itself would endure.

Kanza had other motives as well. She understood that concentrated power among twelve young men—sons of different mothers, tied to different tribal confederations, possessed of different temperaments and ambitions—would produce rivalry, resentment, and eventually violence. To keep them all in Fez would be to place them in a confined arena where competition for precedence, resources, and recognition would inevitably escalate. Distance, by contrast, allowed each to build his own legitimacy, his own authority, his own identity, without the constant friction of comparison and contestation.

And she understood something darker still. The Abbasid apparatus that had killed her father, her husband, and her son did not operate only through poison. It operated through bribery, infiltration, and manipulation. If trained mawālī could be placed at the imām's table, then trained concubines could be placed in the imām's bed. If advisors could be bought, then so could wet nurses, stewards, and secretaries. If a dynasty could be killed directly, it could also be destroyed indirectly—by sowing distrust, amplifying grievances, and turning brother against brother. After five successful assassinations, why would the Abbasids not escalate to psychological warfare? Why would they not plant rumors, engineer disputes, and manipulate the very succession itself?

Kanza could not prevent this entirely. But she could limit its damage by ensuring that even if one branch of the family was compromised, corrupted, or turned against the others, the remaining branches would survive, geographically separated, politically autonomous, and therefore harder to manipulate as a collective.

Her strategy, in short, was prophylactic. Not in the weak sense of avoiding conflict—conflict, she knew, was inevitable—but in the strong sense of ensuring that no single conflict, no single betrayal, no single assassination could decapitate the entire line. What she could not prevent, however, was the constitutional tension her own division had created.

The crisis crystallized under Muḥammad ibn Idrīs, known as al-Khalīfa, who ruled from Fez. His most consequential decision was the monopolization of the mint, restricting the striking of the Idrīsid dirham to al-ʿĀliyya alone. In a state whose economy depended exclusively on silver—gold being monopolized by the Midrārids of Sigilmāsa—control of the mint was control of sovereignty itself.

ʿĪsā ibn Idrīs, governor of Tadla, Tāmasnā, Dukāla, and the Atlas, did not initially rebel. Raised in Fez, educated within the Idrīsid court, he governed with competence and loyalty. His break in 215/830 was not ideological. It was economic and structural. The silver mines of Jabal ʿAwwām, Wāziqqūr, Zīz, and Tudgha, lay within his sphere. When Muḥammad al-Khalīfa denied the brothers the right to mint, he effectively reduced them to governors without fiscal autonomy. ʿĪsā responded by striking coinage at Wāziqqūr near Khénifra, asserting not independence from the imamate, but participation in it. The response from Fez was war.

Isāwi Dirham

Silver dirham issued under Imām'Isa ibn Idris al-Anwar at Wazzaqur mint in 225/840.

This conflict must be understood through the lens of age and manipulation. When it erupted, Muḥammad was in his early twenties at most. ʿĪsā, a year or two younger, was known even then for his charisma and force of personality. These were not seasoned statesmen weighing constitutional principles in council chambers. They were young men—sons of a murdered father, grandsons of a murdered grandfather, surrounded by advisors whose loyalties were unknown, married to women whose families had their own interests, and governing territories they had only recently inherited.

The mint monopoly was, on its surface, a reasonable assertion of central authority. Muḥammad, as the second-born son and ruler of Fez, had a legitimate claim to regulate the currency that bore the family name and the Qurʾānic inscriptions that declared their mission. To allow each brother to mint independently risked debasement, confusion, and the fracturing of monetary sovereignty—an outcome that would weaken the dynasty in the eyes of both internal populations and external rivals.

Yet ʿĪsā's position was equally coherent. He controlled the source of the silver itself. To deny him the right to mint was to transform him from an autonomous amīr—a prince of the House of Mawlay Idrīs, governing a real territory with real resources—into a subordinate administrator, dependent on Fez for the very coins needed to pay his soldiers, feed his administration, and demonstrate his legitimacy. It was, in effect, to strip him of sovereignty while leaving him with all the responsibilities of rule.

The conflict, therefore, was not about greed or ambition. It was about the unresolved question at the heart of Kanza's division: Were the brothers co-rulers of a shared imamate, or was one brother the imām and the others merely his governors?

Muḥammad's monopoly implied the latter. ʿĪsā's minting asserted the former. And because this question had never been formally answered—because Kanza's division had been executed in haste, under duress, with a dozen young boys to protect and no time to draft a constitution—it remained ambiguous. Ambiguity, in the hands of young men under pressure, becomes conflict.

But there is another layer to this crisis that the sources hint at but do not explore. By the time Muḥammad and ʿĪsā clashed, the Abbasid intelligence apparatus had already successfully assassinated five key figures in the Idrīsid project: Idrīs I, Idrīs II, Isḥāq, Rāshid, and others whose names are lost. These were not random murders. They were systematic operations, requiring long-term infiltration, the cultivation of insider access, and the ability to position agents close enough to the imām's household to administer poison without detection.

If such an apparatus existed—and the historical record confirms that it did—why would it stop at direct assassination? Why would it not also seek to destabilize the family through indirect means: planting concubines who whispered division, cultivating viziers who amplified tensions, bribing stewards who framed disputes in the worst possible light, and shaping the very advice that young, inexperienced rulers received?

When Muḥammad decided to monopolize the mint, was it his own idea? Or was it the suggestion of an advisor who understood that such a move would provoke ʿĪsā? When ʿĪsā struck coins in defiance, was it purely a principled response? Or had his own counselors framed Muḥammad's decision as an unforgivable insult, an assault on his dignity and autonomy, something that could not be tolerated without loss of honor?

We do not know. The sources do not tell us. But to treat the conflict as if it emerged purely from internal Idrīsid dynamics—as if young men in their twenties, ruling a fragmented state, surrounded by advisors of uncertain loyalty, were making decisions in a vacuum—is to ignore the documented reality of Abbasid operations across the Islamic world.

What we do know is this: the conflict escalated without mediation. No council of elders was convened. No arbitration was attempted. No senior figure from the family—no uncle, no respected scholar, no tribal leader with ties to both brothers—stepped forward to defuse the tension before it became war. This absence is suspicious. Either such figures did not exist, which seems unlikely given the extensive kinship and tribal networks the Idrīsids had built, or they were prevented from acting, sidelined, discredited, or otherwise neutralized.

This war was, as later sources implicitly admit, economically inevitable but politically disastrous. No mediation was attempted. No council was convened. The absence of mediation is made more striking by the silence surrounding Kanza herself. Where was the grandmother who had orchestrated the division? If she still lived, why did she not convene the brothers? The sources do not tell us. But her absence—whether through death, illness, or marginalization—removed the one figure who might have prevented the war. Without Kanza, the protective architecture she had built had lost its keystone.

Al-Qāsim, governor of Tanga and Sabta—the most perceptive of the brothers—refused to take part. His withdrawal was not cowardice but foresight. As the eldest, al-Qāsim had watched his father die young and his uncles fall to Abbasid poison. He understood something Muḥammad had not yet grasped: that the Idrīsid house could withstand external enemies, but not fratricidal war. Once brothers turned their swords against one another, legitimacy itself would erode, and the Abbasids would no longer need poison. His refusal, preserved in verse, marks one of the earliest internal critiques of Idrīsid strategy—and it led him to withdraw from the struggle into a small settlement near Tanga, where he established a ribāṭ: a space of watchfulness and restraint rather than conquest, quietly prefiguring a form of authority that would become foundational to Moroccan Sufism.

But al-Qāsim's wisdom did not prevail. Muḥammad entrusted the campaign to ʿUmar, another brother, vigorous and loyal. ʿUmar led forces south into the Atlas and defeated ʿĪsā at Wādī al-ʿAbīd. Yet this was not a decisive victory in any meaningful sense. ʿĪsā was not killed. He was not captured. He withdrew—strategically, deliberately—into Ayt ʿAttāb and the fortified settlements of the interior, preserving his followers, his resources, and his claim. He did not vanish. He waited. And he did not wait long.

When Muḥammad al-Khalīfa and his brother ʿUmar were assassinated in 221/836, the political landscape shifted. Authority in Fez weakened. A child, ʿAlī Ḥaydara, ascended nominally, ruling in name rather than power. In this vacuum, ʿĪsā re-emerged, restored his emirate, expanded southward as far as Sūs, and resumed silver dirhams at Zīz in 229/843. His resumption of minting was now explicit and public, and the numismatic record confirms that he adopted the caliphal-style laqab al-Muntaṣir Billāh—the very title previously borne by his brother Muḥammad—signaling transfer of authority.

What later becomes unmistakable is that ʿĪsā’s horizon was never limited to Tadla or the Atlas. His objective was Fez itself. Between 266/880 and 279/893, numismatic evidence demonstrates that Fez was ruled not by the line of Muḥammad al-Khalīfa, but by members of ʿĪsā’s own branch. Coins struck in the city during this period bear the names of his descendants, leaving no doubt that control of the capital passed into their hands. This was not an anomaly or a momentary seizure; it was the delayed fulfillment of a political trajectory set in motion decades earlier.

The Idrīsid crisis, therefore, was not a rebellion against legitimacy, but a struggle over how legitimacy should be exercised. The assassinations were not anomalies. They followed the same pattern that had claimed Idrīs I, Idrīs II, Isḥāq, and Rāshid. Muḥammad, who had sought to concentrate authority in Fez and monopolize the mint, was dead. ʿUmar, who had been rewarded with the governorship of Tanga for his victory over ʿĪsā, was also dead. Both had been young men and both had been visible, centralized, and therefore targetable. And both had been in Fez, or operating closely within its orbit.

Meanwhile, ʿĪsā—who had been defeated militarily, driven from his initial base, and forced into the Atlas—survived. Al-Qāsim, who had refused to participate in the war and remained in his ribāṭ, survived. Dāwūd, stationed at Taza in the eastern corridor, survived. The brothers who had been dispersed, who governed their own regions with autonomy, who were not gathered under a single roof or dependent on a single table—these were the ones the Abbasid apparatus could not reach. The pattern was undeniable. Kanza had been right.

The succession of ʿAlī ibn Muḥammad, later known as Ḥaydara, was a constitutional improvisation born of necessity. He was a child—some sources suggest he was no older than ten or twelve—and his authority was nominal at best. Real power fragmented among the surviving brothers, regional strongmen, and the tribal confederations that had initially supported the Idrīsid rise. Fez did not collapse, but neither did it command. It became one center among many, primus inter pares in theory, but structurally incapable of enforcing obedience. And in this fragmentation, something unexpected occurred: the Idrīsid project did not end. It adapted.

And what came next was not retreat into irrelevance, but something the conventional narrative of dynastic decline fails to anticipate: the Idrīsids began building again, especially in the north.

Al-Baṣra near Asilah emerged as a renewed Idrīsid center, while Jarāwa near Tlemcen secured the eastern frontier against Aghlabid pressure. In the Rif, Ḥajar al-Naṣr was constructed as a deliberate stronghold controlling tribal routes, not as a refuge of retreat. Tiṭwan (Tetouan), developed as a fortified castle on the remains of Tamuda, took shape during sustained conflict with the Umayyads and their Zanāta clients, locking the northern frontier and the strait. To these must be added Jawṭa (Jūta) on the Subū: a thriving river-port and market whose prosperity gave rise to the Idrīsid branch of al-Jawṭī, later called upon to govern Fez after the fall of the Marinids. Its commercial intensity left a cultural trace in the vernacular term “Jūṭiyya”, used for markets so dense with merchants and customers that trade itself seems to overflow. Together, these foundations mark a decisive shift from a single capital to a distributed Idrīsid geography of power, urbanity, and memory.

The archaeological site of Qalʿat Ḥajar al-Nasr, located in Douar Dar al-Rāṭī (Zaʿrūra Commune, Larache Province), is closely linked to Idrisid history in northern Morocco. Established as a fortified refuge in the 4th/10th century, it reflects the Idrissids’ struggle for survival during a period of political fragmentation and persecution. The site preserves both the shrine of Aḥmad Mazwār ibn ʿAlī Ḥaydara ibn Muḥammad ibn Idrīs ibn Idrīs—an important figure of the Idrisid sharifian lineage—and the archaeological remains of the stronghold itself. Tradition attributes the foundation of this fortress-city to Prince Muḥammad ibn Ibrāhīm ibn al-Qāsim ibn Idrīs ibn Idrīs, around 318/930, highlighting its role as an Idrissid mountain bastion and memory site.